Here’s how you can do the best for patients who may have suffered sexual assault

Sexual assault can happen to anyone. It is independent of personal traits such as strength, intelligence and influence.

The following are some salutary statistics from the Australian Bureau of Statistics:

- 17% of all Australian woman and 4% of Australian men reported having experienced sexual assault since the age of 15

- 30% of sexual assaults and related offences are reported to the police

- 20% of women who have been sexually assaulted do not tell anyone about it

- The health profession a woman is most likely to disclose sexual assault to is the GP

- Partner rape has particularly low reporting prosecution and conviction rates

Case scenarios

Miranda, 24, is a new patient. She appears upset and uncomfortable, and asks for a “full check-up”. She says last month she attended a work meeting and had several drinks. She has a patchy memory of the evening’s events, until she woke up in a hotel room, in bed with a man she didn’t know. She felt dizzy and hungover, and now is scared she may be pregnant. She tells you she is normally very careful about sex and would always use a condom with a new partner…

Frieda, aged 38, is visiting the city for a medical appointment. She has come to your afterhours GP service about bruises on her breast. She met a man on a dating app and had consensual sex. The next day they met again. He locked her in the room, insisted on sex without a condom and punched her breasts…

Greg, aged 22, is intellectually delayed and does not speak. His parents bring Greg to see you, reporting that he came home this afternoon from a day trip with a new carer (male) rather agitated and upset. This evening his Dad noted blood in his underpants when he changed him…

Anh, aged 35, speaks limited English. She tells you the boss keeps asking her to stay late when everyone else has left the factory…

Each of these cases raises multiple issues, and management will be guided by patient preferences.

Here are some practice points to consider.

Has sexual assault taken place?

• Miranda may have been assaulted. Note that the law varies from state to state, but under NSW law, a person cannot consent to sexual activity if they are substantially intoxicated, asleep or unconscious

• Frieda has been sexually assaulted

• Greg’s parents are worried about sexual assault. This needs to be considered as one of the differential diagnoses of his anal bleeding

• Anh is being exploited in some way. She is vulnerable to sexual assault and it would be helpful to explore with her what is happening, and also her understanding of her rights as an employee in Australia

Obtaining the history

All of these cases have gaps in the history and missing details. This is common after sexual assault. An incomplete history does not prevent a person from reporting a sexual assault to the GP or the police.

Patients may have trouble explaining exactly what happened due to embarrassment, shame or self-blame, or because they have memory gaps surrounding the events. The physical examination is often normal, but the emotional trauma may be overwhelming.

Patients may be confused and perhaps frightened of reporting the assault to anyone. Their fear may be related to privacy concerns, going to a police station, the fear of being deported, or because they were taking recreational drugs.

Younger clients may even be worried about reporting just because they hadn’t told their mum or dad that there would be boys at the party.

Being unable to resist the assailant, or freezing, is also common during sexual assault and does not in any way diminish the victim’s right to the protection of the law.

Common barriers to reporting sexual assaults

• Sexual assault is a frightening, humiliating and traumatic experience. Victims may feel overwhelmed, ashamed and anxious. Some people just want to forget and may think, rightly or wrongly, that it will go away if they don’t talk about it

• Victims worry they won’t be believed

• Victims worry they will be blamed for the assault

• The rape myths and victim blaming are pervasive, and a person who has just been abused will often be feeling doubtful about what sort of reception they will receive if they disclosed

Advantages of reporting

It is therapeutic just to tell another person who can provide support and reaffirm that no one should be treated like this, especially if the person offering that reassurance is a trusted professional.

A simple response to a situation of disclosure of sexual assault, however long ago, would be:

• “I am very sorry that happened”

• “I am pleased that you told me” or “It must have been hard to tell me”

• “No one deserves to experience that” or “What you are describing is sexual assault” or “That is a crime”

• “Would you like to talk more about this?”

After being told of an unwanted sexual experience, the GP is able to offer information about specialised sexual assault forensic and counselling services.

There is an excellent section on listening to and validating a sexual assault victim in the RACGP white book.

Preserving the evidence

If the patient wants to go ahead with a forensic examination, the GP can give advice that helps preserve the evidence, and can also collect early evidence, while the forensic examination is arranged.

The patient should be told the following:

1. Not to shower or bathe

2. To keep, and not wash, clothing worn during, or immediately after the assault

3. If the assault was in the last 24 hours and the patient needs to use the toilet, then ask them to:

• Gently press their underpants (or sterile gauze) into the vulva or anal region before using the toilet and to store the pants or gauze (in a urine jar is a good option) to give to the forensic service provider

• Avoid wiping afterwards (gentle dab if necessary)

• If there was a penile – oral assault, avoid eating, drinking or washing mouth

In case of suspected drugging, if there might be a delay before forensic examination, the GP could consider collecting and labelling a blood and sterile urine sample. Phone the forensic examiner or a Sexual Assault Service for advice on collecting and storage/transport.

Reassure the patient they have done the right thing to come forward. Do not question them for a detailed account of events, beyond clarifying medical needs.

Legal and police process

Sexual assault is a serious crime. Where possible, a specially trained police officer will respond to victims of sexual assault.

A victim can report to the police and ask for general advice, or provide information, before deciding to make a formal statement.

Prompt reporting allows the police to begin an investigation and collect evidence such as CCTV, crime scene evidence (such as sheets or other DNA sources) and obtain witness statements. Evidence can be lost with delay.

There is no compulsion on an adult victim to continue the legal process all the way to court. Many victims seek counselling or further information before deciding whether to proceed. Reporting to the police keeps all options open.

Some victims report specifically, and altruistically, in order to help other potential victims of the same assailant. Some rapes are part of a pattern of predatory behaviour, and the victim can be helped by seeing that, for example, a taxi driver who pulled over and raped them is likely to have done this before and would do it again. The information or DNA swabs that they can provide to the police may help protect others.

The forensic medical examination

Forensic medical examinations in Australia are often provided by GPs who have received varying degrees of forensic training, and ideally work as part of a medical unit or a team supported and led by a forensic physician. Sexual Assault Services best operate as a team service, with counselling and medical staff offering a joint response.

Forensic medicine is increasingly becoming established as a specialty in Australia, with the establishment of the Faculty of Clinical Forensic Medicine in the Royal Australasian College of Pathologists.

Forensic medical examinations can be performed only with the consent of the sexual assault victim, and are responsive to the patient’s health concerns. Doctors who do this work assess the medical and forensic concerns of the victim. A sexual assault counsellor can provide information on legal options and offer support and counselling. Where counselling is not available face to face, it is available Australia-wide through a 24/7 number or online at Rape and Domestic Violence Services Australia.

Forensic examination includes the following:

• Recording of a careful history of the assault to guide the examination and specimen collection

• Head-to-toe examination of the patient, for injury and trace evidence

• Specimen collection and sampling for DNA

• Toxicology if applicable

• Careful documentation of any injuries, with body diagrams and clinical photography

The examining doctor will write a report, or Expert Certificate, which can be used in court.

The certificate offers a medical opinion to explain the physical findings with an objective opinion on these findings, in relation to the history provided.

Sexual health risk and pregnancy prevention

Emergency contraception is offered to all women at risk of pregnancy. Within 72 hours since unsafe sex, levonorgestrel 1.5 mg (norLevo-1) is offered immediately. If between 72 hours and 120 hours since unsafe sex, ulipristal acetate 30mg (Ella One) is an option. Ulipristal acetate is considered first-line for women with a BMI of more than 30.

Patients can be reassured that emergency contraceptive pills are considered to work by preventing fertilisation. This means they do not harm an established pregnancy and specifically do not prevent the implantation of a fertilised ovum.

Alternatively, a copper IUD can be used as emergency contraception for up to five days after unsafe sex.

Baseline urine PCR testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea is performed.

Hepatitis B vaccination is offered if the patient is not immune or if history of immunisation is unclear.

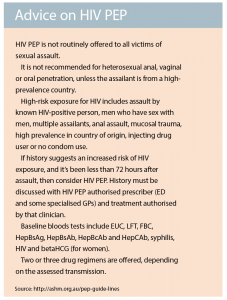

Post-exposure HIV prophylaxis should also be considered in cases deemed at risk of HIV transmission.

Full STI screening two weeks after the assault is advised; recommendations include blood for hepatitis B and C, HIV, syphilis and ßHCG for pregnancy. Further testing at three months after the assault, with blood for hepatitis B and C, HIV and syphilis, is also advised. If there is a concern about increased risk of hepatitis C, a further blood test is done at six months.

Adult survivors of childhood sexual assault

Patients may disclose sexual assault for the first time a few days or many decades after the event. For advice on appropriate responses, go to the RACGP guidelines white book.

Always consider whether there could be children still at risk, and whether mandatory reporting applies. Your medico-legal insurer can provide ethical and legal advice.

Responding to disclosures or concerns about sexual abuse in children is beyond the scope of this article.

What about self-care?

Think about protecting yourself, your family and your staff from the effects of being exposed to vicarious trauma. Take care with privacy and confidentiality of medical notes – this is of the utmost importance, and is a significant patient concern.

In addition to general measures to handle stress, consider formal debriefing sessions with a colleague or debriefing with a psychologist or sexual assault counsellor.

Avoid dumping your stress on staff or a spouse who doesn’t want to hear. Responding to signs of stress in a timely manner helps limit the negative effects on you, your family and your practice team.

There are special issues for the GPs in a smaller community where either, or both, the victim and the perpetrator are known to the doctor. It is not the GP’s role to mediate.

Summary

While certain populations are more vulnerable and over-represented in sexual assault presentations, sexual assault can happen to anyone.

A variety of physical and mental health presentations in general practice may relate to a past or recent sexual abuse. Being well informed about local services and referral options is valuable, but when in doubt, prompt advice can be obtained by phoning 1800 RESPECT. Offering non-judgemental support and information about management choices empowers the patient to choose the best option for their individual needs.

Dr Rosemary Isaacs is Staff Specialist in Forensic Medicine and Sexual Assault at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

Dr Mary Dobbie is Visiting Medical Officer in Sexual Assault at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital