A new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics gives guidance for combatting a growing issue.

Children with mental health, emotional and behavioural (MEB) problems have an eight-fold increased risk of death by suicide than children without, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

The academy has released an update to the 2015 clinical report on child MEB, calling for frequent screening starting as early as six months of age and continuing until they’re 21 years old.

MEB screening tools should be conducted at six, 12, 24 and 36 months of age and then annually, as well as screening for caregiver MEB problems such as perinatal depression and caregiver-child relational problems.

Extra screening and surveillance should be considered whenever concerns are raised by caregivers.

This is in addition to the recommended developmental screening at nine, 18 and 30 months, and autism spectrum disorder screening at 18 and 24 months.

The AAP report also recommended starting depression and suicide risk screening at the age of 12 years.

Suicide became the second leading cause of death in children aged 10 to 14 years and the third leading cause in youths aged 15 to 24 years in 2020.

The rate of suicide in these age groups have increased more than 40% from 2000 to 2017.

The AAP report incorporated recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, the National Institute of Mental Health and other recent AAP reports.

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES ARE INCREASING

The last national Child and Youth Mental Health Survey (aka Young Minds Matter survey) showed that 14% of Australian children aged 4-17 years meet criteria for a mental health disorder over 12 months, Professor Harriet Hiscock, paediatrician and researcher at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, told The Medical Republic.

“This study was done in 2014, and we are meant to be having a new national survey soon,” she said.

She discussed the 2024 Australian Early Development Census, which showed that 10% of children starting school were developmentally vulnerable in the domain of emotional maturity, an increase from the census three years earlier.

Nearly 11% were vulnerable in the domain of social competence.

“We have seen increases in children attending emergency departments for mental health issues (not a great place for kids) and this represents the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in worsening mental health in young children,” she said.

The AAP report cited a 2023 study in which annual MEB screening was conducted from ages two to six.

Researchers had found that nearly 34% of children had trajectories of increasing MEB severity on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) as they aged.

There was growing evidence that young children with significant irritability were more likely to be diagnosed with MEB problems when they reach school age, the report stated.

This includes extreme, unpredictable and prolonged tantrums, frequent dysregulation and problems with anger regulation.

THE CURRENT STATE OF SCREENING

“We lack regular touch points in our healthcare system to ask about young children’s MEB,” Professor Hiscock said.

In some states, especially Victoria, there was good attendance at free, universal Maternal and Child Health Nurse visits, she said.

However, attendance tended to fall below 80% after the child turned one year of age and in other states, attendance had been well below 30%.

“I believe that annual checks should be done from birth to school entry to detect early any child MEB and associated risk factors such as parent (mothers AND fathers) mental health problems so we can address them and get our kids on the right track,” Professor Hiscock said.

“GPs do not do any annual child health development checks although Minister Butler has signalled he will bring in a three-year-old check,” she said.

“This is welcome but misses the fact that a child can develop MEB over time so really, there needs to be consideration of an annual check.”

She explained that the US system had regular well child visits which allowed for repeat MEB screening, but the data on uptake of these services was variable across the country.

The AAP also said that nearly 40% of US children would have an MEB disorder diagnosed by the age of 16 years, with the most common diagnoses being disruptive behaviour problems, ADHD, anxiety and mood disorders.

Related

The report estimated that up to a fifth of US children have a behavioural or emotional disorder at any given time, including children as young as two years of age.

Screening involved a commitment from both caregivers and primary care clinicians, as the tools were parent-completed but required interpretation from health professionals.

Professor Hiscock said that screening needs to be appropriately resourced in terms of time, training and funding.

There also needed to be appropriate referral pathways in place.

“There is no point, and in fact harm, in screening without having support pathways available to families,” she said.

She pointed to the recently released National Guidelines for including mental health and wellbeing in early childhood health checks, which provided recommendations for incorporating mental health into well child checks.

“It advocates for use of the child mental health continuum as a tool to elicit parent concerns rather than a formal screening measure,” she said.

“Importantly, it also advocates for the need to ask about social determinants of mental health e.g. poverty, food insecurity, parent mental health, family violence etc.

“This is key because parents cannot support their child’s mental health if their own mental health is under threat.”

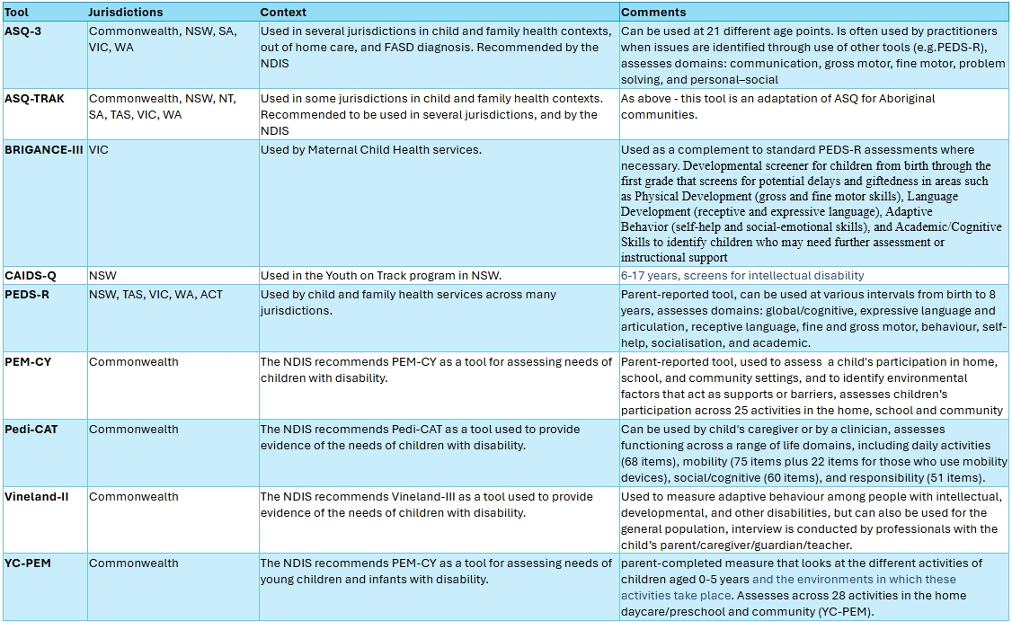

SCREENING TOOLS

MEB screening tools changed based on age, and a single appropriate tool for all children and diagnoses did not exist, the report noted.

While the use of standardised screening tools may remove bias to help reduce misdiagnosis, they themselves were not diagnostic; they simply categorised the level of risk.

Professor Hiscock said screening tools were not perfect and could result in a false positive diagnosis, but they tended to become more reliable as the child gets older.

The report explained that various screening tools are available, but the choice of which to use depended on many factors.

Professor Hiscock provided a comprehensive table of tools but said it was likely that more than this were being used.

Professor Hiscock highlighted the PEDS-R (Parent Evaluation of Developmental Status-revised), a broad developmental screening tool that could be completed by parents and helped identify any concerns about their child’s development.

“Parents know their children best, so having them complete the PEDS-R, and then having a conversation with their maternal and child health nurse or other health practitioner, is an evidence-based method for identifying early developmental challenges,” she said.

The tool screens for developmental, behavioural, social-emotional and mental health concerns in children under eight years of age.

The Centre for Community Child Health, a department of the Royal Children’s Hospital and national PEDS-R distributor, recommends the use of the tool to support identification of developmental concerns, including MEB, and to facilitate engagement between parents and health practitioners.

The AAP recommended clinicians familiarise themselves with sociodemographic characteristics of the normative population that was used in the validation of the screening tools to ensure they used the one that best reflected their specific patient population.