Symptomatic colloid cysts need early definitive treatment which, in the majority of people, is highly effective, writes Dr Parvathi Menon

The colloid cyst is a rare intracranial tumour.

It is now understood to be of endodermal cell origin1-3 as opposed to earlier hypotheses of their having a neuroepithelial cell origin like choroid plexus tumours.4

Colloid cysts have a mucinous content ranging in colour from green to brown and occasionally solid.5 Previously the cyst was thought to contain only clear mucinous material, which is why it was defined as a colloid “cyst”.

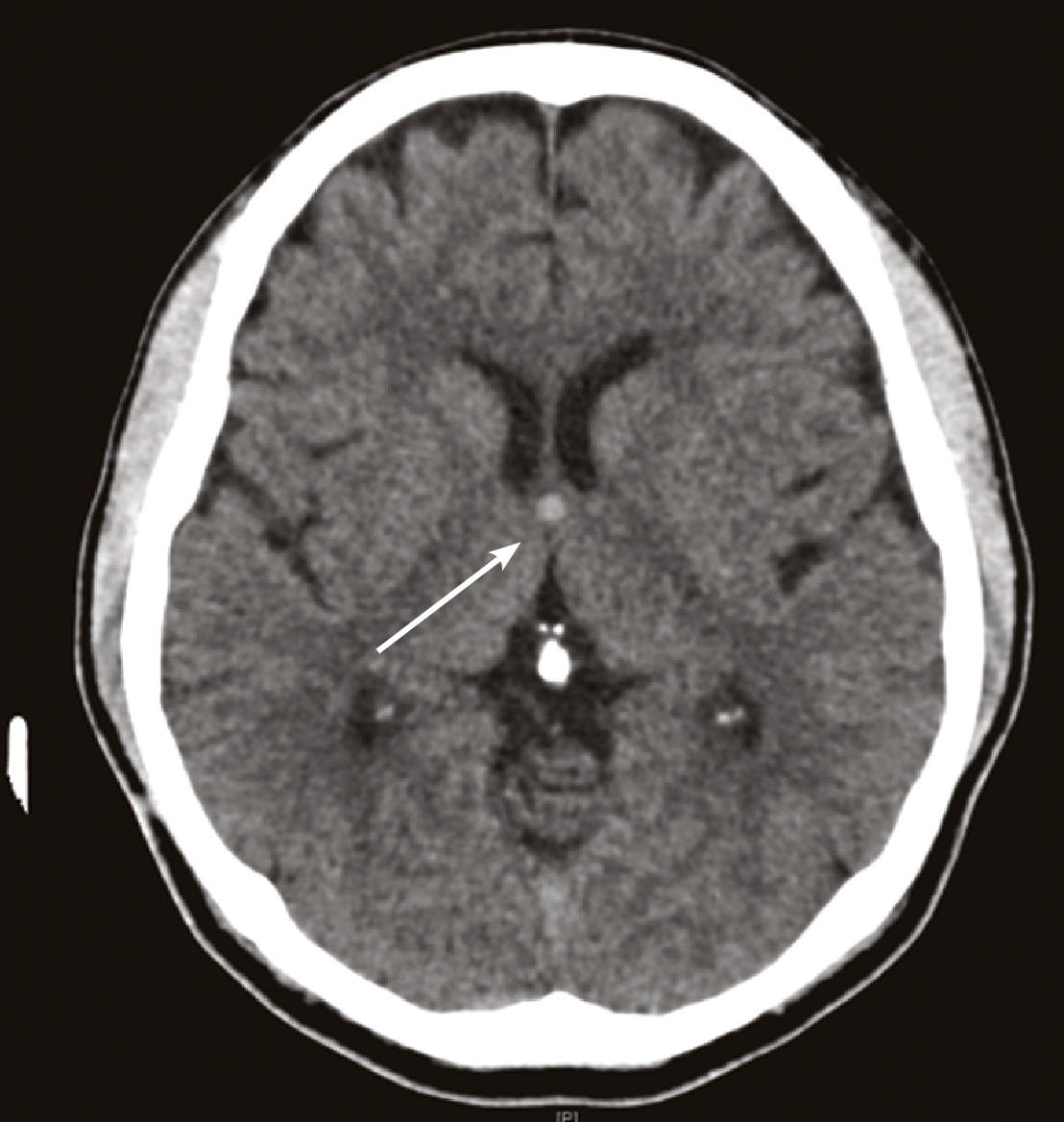

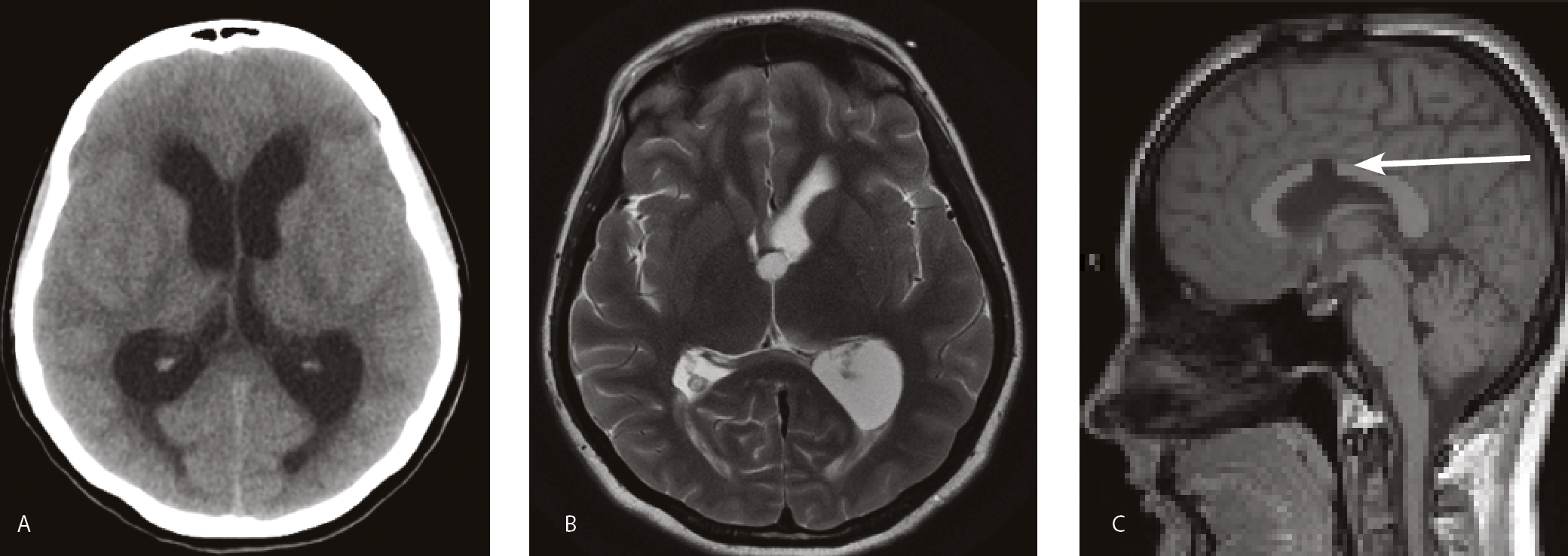

Colloid cysts commonly arise from the roof of the third ventricle (See figure 1 – At right) in close proximity to the interventricular foramen of Monroe connecting the third and lateral ventricle and cause symptoms by obstruction of the flow of CSF.6 (See figure 2 A,B – Page 33).

Other locations for colloid cysts have also been described including an intrapontomesencephalic lesion with lower cranial nerve palsy and pyramidal deficits.7

Colloid cysts of the fourth ventricle present with ataxia, nausea and vomiting 8 and colloid cysts of the septum pellucidum also present with headache and features of CSF obstruction9.

However, as the commonest location of symptomatic colloid cysts remains the third ventricle, further discussion on the presentation, prognosis and management of colloid cysts will be confined to those of the third ventricle.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

An Australian retrospective series10 over 18 years reports that colloid cysts constituted 1.6% of all brain tumours managed in a neurosurgical unit. This is in keeping with other series which puts the range between 0.2 to 2% of all intracranial neoplasms. A Finnish retrospective series over 14.5 years estimates that the population incidence of colloid cysts is 3.2 per million per year.11

Colloid cysts are usually symptomatic between the ages of 20 to 50 years11-13 although they can occur at any age. They are slightly more common in males with an average male to female ratio of 1.5:1, 6 including those people with the incidental finding of a colloid cyst.12

In addition, familial series of colloid cysts have been reported14 albeit rarely. While no genetic predisposition has been identified, as yet, screening in families with two affected first degree relatives has been proposed.14

PRESENTATION

According to a US retrospective series, the majority of patients with third ventricle colloid cysts are asymptomatic, (60%) with the cyst being detected incidentally on brain imaging for unrelated conditions (See figure 3 – Page 34) (40%).12

The symptomatic group generally develop symptoms from obstruction of CSF flow by the colloid cyst.

The four commonest presenting symptoms being:

(1) headache associated with

(2) nausea or vomiting,

(3) blurred vision or diplopia,

(4) dizziness or gait ataxia.11-13

Other less frequent presenting symptoms include cognitive and memory dysfunction, syncope, bradycardia, seizures and urinary incontinence.

In the US study, only a small percentage (8.8%) of the patients with a colloid cyst who were asymptomatic went on to develop symptoms or signs requiring intervention over the subsequent five years, and a small number (3.3%) showed cyst regression12 radiologically over that same period.

PROGNOSTIC FEATURES

Colloid cysts can occasionally be fatal, with acute obstructive hydrocephalus and brainstem herniation resulting from rapid colloid cyst enlargement.12, 15 Among symptomatic patients the risk of death is estimated to be 3.1%.12

Acute obstructive hydrocephalus appears to occur post-traumatically.12

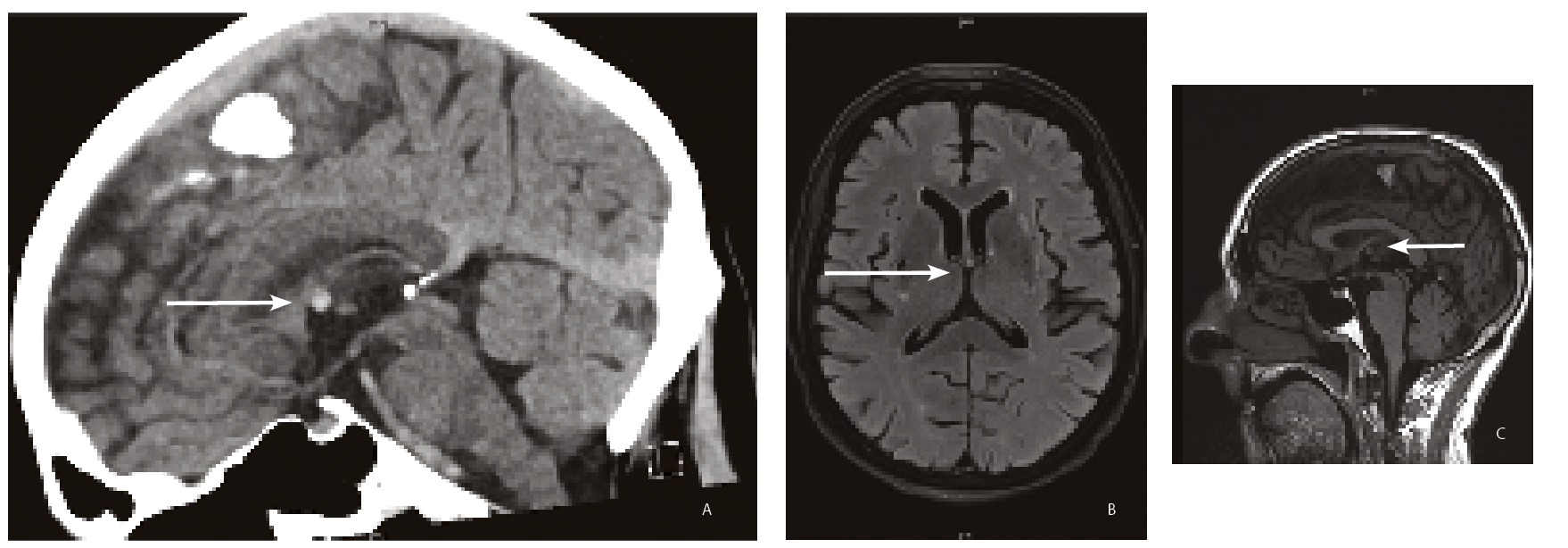

Patients with symptomatic colloid cysts tend to be younger, have significant headaches, larger cyst size (more than 8mm), ventriculomegaly on cerebral imaging and hyperintense cyst signal on T2 weighted imaging.12 15 These are also the risk factors for hydrocephalus from colloid cyst-associated, CSF flow obstruction.

A proposed colloid cyst risk score (CCRS)12 defines high risk colloid cysts as those occurring in patients less than 65 years, with cyst axial diameter more than 7mm, hyperintensity of the cyst on FLAIR MRI imaging and presence of the cyst in a high risk zone of the third ventricle marked on sagittal MRI T1 sequences.

RADIOLOGY

A colloid cyst of the third ventricle generally appears hyperdense (bright) on a CT scan, with the signal quality dependent on the protein and cholesterol content of the cyst.16, 17

In addition, ventricular enlargement and periventricular hypolucency may also be seen with obstructive hydrocephalus. Rarely the colloid cyst may be hypo or isodense with brain parenchyma or may show signal change from haemorrhage or calcification.18

Magnetic resonance imaging reveals colloid cysts which are usually hyperintense on T1 weighted scan (T1W) and the signal is related to the cholesterol content of the cyst17, 18 and hypointense on T2W sequences with mixed signal and fluid levels also reported.18

Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) sequences also show hypointense signal with most colloid cysts.Hyperintense signal with FLAIR sequences has been described as a poor prognostic marker in symptomatic patients closely associated with obstruction and clinical deterioration.12

MANAGEMENT

Asymptomatic colloid cysts may be managed conservatively with clinical and imaging follow up if the cyst size is less than 7mm and there is no evidence for ventriculomegaly.12, 15

Symptomatic colloid cysts need surgical resection (See figure 2 B,C – at right) while additional procedures of CSF shunting and cyst aspiration may be involved in some cases.

A meta-analysis of operative series between 1990 and 20146 suggests that microsurgical resection results in more complete cyst excision with a lesser incidence of cyst reoperation (1.48%) than endoscopic procedures (3.91% recurrence). However, microsurgical resection is associated with greater procedure-related morbidity (16.3% versus10.5%).

Morbidity associated with microsurgical resection of colloid cysts includes seizures, memory deficits, intracerebral haemorrhage, and meningitis.

Mortality and requirement of post procedure CSF shunting is similar between the two groups.

While microsurgical techniques are associated with greater procedure-related morbidity, they currently have better outcomes for colloid cyst clearance and also have the advantage of having been in use for longer with longer duration follow-up data.

However, endoscopic techniques, are continuing to advance and may in the near future have comparable rates of cyst clearance while being associated with lesser morbidity.

CONCLUSION

Colloid cysts are uncommon intracranial neoplasms which in the majority of instances are asymptomatic.

Symptomatic colloid cysts need early definitive treatment which, in the majority of people, is highly effective. Asymptomatic colloid cysts, detected incidentally, may be safely managed with monitoring alone until symptoms occur, or there is evidence of ventriculomegaly or cyst enlargement on imaging at which time intervention is warranted.

Evidence suggests that asymptomatic cysts do not progress to life threatening outcomes without a prodrome, a preceding head injury or the rare instance of cyst apoplexy resulting in haemorrhage into the colloid cyst.

Dr Parvathi Menon, PhD FRACP, is a specialist neurologist, Westmead Hospital, Western Clinical School, University of Sydney

Acknowledgement: Images in Figure 1, 2 and 3 were contributed By Dr Samer Ghattas, BSc, MBBS, FRANZCR; MRI Fellow, Westmead Hospital.

References:

1. Lach B, Scheithauer BW, Gregor A, Wick MR. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle: a comparative immunohistochemical study of neuraxis cysts and choroid plexus epithelium. Journal of neurosurgery. 1993;78(1):101-11.

2. Graziani N, Dufour H, Figarella-Branger D, Donnet A, Bouillot P, Grisoli F. Do the suprasellar neurenteric cyst, the Rathke cleft cyst and the colloid cyst constitute a same entity? Acta neurochirurgica. 1995;133(3-4):174-80.

3. Macaulay RJ, Felix I, Jay V, Becker LE. Histological and ultrastructural analysis of six colloid cysts in children. Acta neuropathologica. 1997;93(3):271-6.

4. Shuangshoti S, Netsky MG. Histogenesis of choroid plexus in man. Developmental Dynamics. 1966;118(1):283-315.

5. Ho K, Garcia J. Colloid cysts of the third ventricle: ultrastructural features are compatible with endodermal derivation. Acta neuropathologica. 1992;83(6):605-12.

6. Sheikh AB, Mendelson ZS, Liu JK. Endoscopic versus microsurgical resection of colloid cysts: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 1278 patients. World neurosurgery. 2014;82(6):1187-97.

7. Inci S, Al-Rousan N, Söylemezoglu F, Gurçay Ö. Intrapontomesencephalic colloid cyst: an unusual location: Case report. Journal of neurosurgery. 2001;94(1):118-21.

8. Parkinson D, Childe A. Colloid cyst of the fourth ventricle: Report of a case of two colloid cysts of the fourth ventricle. Journal of neurosurgery. 1952;9(4):404-9.

9. Ciric I, Zivin I. Neuroepithelial (colloid) cysts of the septum pellucidum. Journal of neurosurgery. 1975;43(1):69-73.

10. Jeffree R, Besser M. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle: a clinical review of 39 cases. Journal of clinical neuroscience. 2001;8(4):328-31.

11. Hernesniemi J, Leivo S. Management outcome in third ventricular colloid cysts in a defined population: a series of 40 patients treated mainly by transcallosal microsurgery. Surgical neurology. 1996;45(1):2-11.

12. Beaumont TL, Jr. DDL, Rich KM, II FJW, Jr. RGD. Natural history of colloid cysts of the third ventricle. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2016;125(6):1420-30.

13. Mathiesen T, Grane P, Lindgren L, Lindquist C. Third ventricle colloid cysts: a consecutive 12-year series. Journal of neurosurgery. 1997;86(1):5-12.

14. Bavil MS, Vahedi P. Familial colloid cyst of the third ventricle in non-twin sisters: Case report, review of the literature, controversies, and screening strategies. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 2007;109(7):597-601.

15. Pollock BE, Huston III J. Natural history of asymptomatic colloid cysts of the third ventricle. Journal of neurosurgery. 1999;91(3):364-9.

16. Osborn AG, Preece MT. Intracranial Cysts: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation and Imaging Approach. Radiology. 2006;239(3):650-64.

17. Algin O, Ozmen E, Arslan H. Radiologic manifestations of colloid cysts: a pictorial essay. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal. 2013;64(1):56-60.

18. Armao D, Castillo M, Chen H, Kwock L. Colloid cyst of the third ventricle: imaging-pathologic correlation. American journal of neuroradiology. 2000;21(8):1470-7.