If you lift the bonnet, you see assumptions and rushed thinking that look a lot like what led to the failure of Health Care Homes.

Just a couple of weeks before this year’s budget, MyMedicare was called voluntary patient enrolment (VPE).

Awkwardly, only a little over one week before the budget, an obscure agency inside the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, called the Office of Impact Assessment (OIA), completed an assessment of a project it was still calling voluntary patient registration (VPR).

VPR was the name given to VPE by the Medicare Taskforce but VPE had been proposed before that in the Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan 2022-2032 and originally had a planned start date of July 2020.

Someone with a flair for marketing inside the Department of Health and Aged Care (DoHAC) cleverly rebranded it all MyMedicare, just in time for the budget in May.

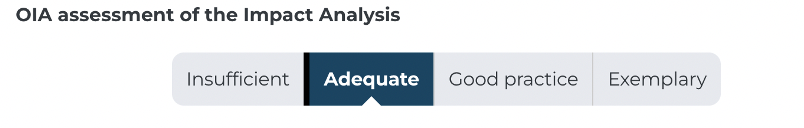

The OIA wasn’t all that impressed with VPR, giving it this bare pass:

In the full 29-page assessment the OIA doesn’t really explain why it gave that mark.

However, a somewhat curt formal letter directly from the head of the OIA to the deputy secretary of DoHAC does: “To have been assessed as ‘good practice’ under the Guide, the IA would have benefited from … further consideration of potential barriers to individuals registering with VPR; the resulting impacts to those who will be restricted from accessing services exclusively linked to VPR; and targeted strategies to address those barriers”.

The comment reveals that the OIA didn’t think that DoHAC had done enough to support a couple of their key assumptions on patient enrolment dynamics, particularly in respect to how many patients might actually enrol and how disadvantaged patients would get enrolled (more on this below).

Of course, the mark of “adequate” already says quite a lot about MyMedicare as it is currently being proposed.

It’s not “good practice” in the view of the OIA, that is for sure.

For a scheme that is being touted as underpinning patient-centric medicine in this country and the major means by which our GP sector will transition smoothly into a “blended” funding model, a mark of “adequate” doesn’t feel like it should even be considered as a pass.

But it passed as far as the government is concerned because it subsequently signed off over $215m in budget funding for the scheme (this figure includes money for the new GP Aged Care Incentive to improve continuity of care by GPs for aged care residents, which they want to connect to MyMedicare).

One would love to know how close to a “fail” (or “insufficient”) the OIA came and how much pressure there was on everyone involved from both DoHAC and the OIA to pass a scheme literally days before it would emerge as a centrepiece of reform in the budget for health?

The OIA document outlines a series of rushed thought processes and assumptions made with little or no evidence to back up the assumptions.

It should make a lot of people nervous about just how robust the planning underpinning MyMedicare is so far.

Problem 1: Not enough detail for GPs to trust it

A major potential problem for the government here is that if GPs start suspecting that MyMedicare is flaky in any way, and with the major fail of Health Care Homes still fresh in everyone’s minds, they might not want to risk spending precious time engaging in the idea and helping much.

So far, your average punter GP on the street wondering what they might be in for with this new program has virtually no meaningful information with which they could make an informed decision on participating in the program or not.

Almost no detail has been made available to them by either the government, or their member organisations, on what MyMedicare actually is, and how it will work.

So far it’s been more or less a rough aspirational idea from the past and reborn inside the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce, probably as some sort of place marker for doing what everyone thought Health Care Homes should have done.

Three name changes and a bare last-minute pass mark from the OIA do little to dispel the idea that despite the idea being tossed around for years, MyMedicare is a rolling (and rapidly iterating) thought bubble about the need to do something on continuity of care.

The AMA put out this short explainer document on VPE for its members in October, but it’s pretty high level and, to some extent, aspirational statement, without gritty detail of what their members might actually be up for if they participate. The RACGP had an explainer on its site but we can’t find it any more.

Both organisations seemed to have accepted the idea without doing any due diligence, although that might be unfair because the dearth of detail provided by DoHAC so far clearly prevents any proper due diligence.

Notably, it’s in the interest of both organisations to back the idea: it comes with the promise of new money and more concentration of patient control with their members.

Importantly for these organisations and GPs, the big ideas and goals of MyMedicare we’ve seen so far in various positioning statements make sense in a system which needs to move much faster to more continuity of care and with that, patient centred care.

It’s just that, “the how” of achieving those goals and aspirations in the plan currently looks pretty flaky.

Flaky like worse-than-Health-Care-Homes flaky.

Add that feeling to an ongoing campaign from some doctor groups to paint the scheme as a trojan horse for capitation in Australia, and there is a risk that MyMedicare may end up still born.

Problem 2: Key assumptions have no evidence base

The OIA document outlines for us in some detail how the government hopes MyMedicare will work.

The problem is, when you look at most of the key assumptions being made it becomes quickly apparent that there is a lot of what looks like wishful thinking and not much evidence-based strategic assessment of that thinking.

A good example is a complete lack of detail or argument to support DoHAC’s estimate of how many patients will enrol in the program.

According to the OIA document, MyMedicare will end up enrolling more than 11.5 million patients Australia wide.

That’s quite an assumption.

It’s outlined in the OIA document as follows:

It is expected that around 52.7 per cent of the [86.1 per cent] eligible patients are likely to register because they will directly benefit from the proposed linked funding packages and MBS items. This represents 45.4% of the Australian population, or around 11.5 million people. Over time as incentives and MBS items are linked to VPR, it is expected that practices will seek to expand their registered population through a greater focus on longitudinal care to patients they may not see regularly. Likewise, as targeted MBS services and incentives are linked to VPR it is expected that some patients will register to gain access to these services.

Most patients wouldn’t know what the MBS is and it’s a big leap to assume that a series of “linked funding packages”, none of which have even been revealed yet, and which no one has done any analysis on in terms of likelihood of marketing success to patients, would cause a patient to suddenly think, “cool, I want to get onto this thing”.

Problem 3: No clear value proposition for patients or GPs

The value proposition for a patient is almost non-existent (so far at least).

And linking “incentives and MBS items” to enrolment is a very one-dimensional way to think about why practices might make the decision to register their patients. There is a lot of devil in the detail of the economics of practice management and return on time investment of GPs which is being assumed away here. We did that all in Health Care Homes with a lot more preliminary work, analysis and thinking, and look what happened.

When MyMedicare was conceived within the Medicare Taskforce, the authors said this about the concept:

“[It] needs to be supported with a clear and simple value proposition for both the consumer and their general practice or other primary care provider. Participation for patients and practices needs to be simple, streamlined and efficient”.

That clear and simple value proposition for patients in the MyMedicare plan, as assessed by the OIA, isn’t there.

Essentialy DoHAC is saying the detail is coming on value proposition, don’t worry about it.

That’s not exactly going to engender a lot of confidence among a time poor and financially stressed GP population who aren’t stupid and can still smell the burning embers of the poor souls who took the risk of participating in the Health Care Homes trials.

Problem 4: Patient consent

Another likely huge problem for which there is no critical analysis is patient consent.

If DoHAC did come up with an amazing sequential program of incentives for patients and practices, new MBS items and great marketing which did attract this huge number of patients and practices to be motivated to enrol, it looks inevitable that the patient consent required to use their data across multiple government platforms and GP practices is going to be a major sticking point for a lot of potential enrolees.

The OIA document points to just how complicated such a process might end up being.

VPR will link healthcare identifiers in such a way that a patient’s Medicare number will be linked to their registered practice (through the Organisation Register), and their preferred provider and multi-disciplinary team (through Medicare Provider Numbers). The system will also link to Health Care Identifiers when available to enable linkages to other digital systems. Through the registration process, patients who belong to particular demographics and cohorts will also be identified, providing a new mechanism for funding reform as MBS items and incentives will be able to be linked to registration.

How is anyone going to explain all that to a patient easily and get them to sign on for their data to be pretty much shared with every care team in town and all sorts of government departments?

The OIA document goes on:

As part of the registration process, participants will be asked to formally consent to participate in the program. This will include consent for their registration and demographic data to be visible to the registered practice, stored by Services Australia in a secure database and provided to the Department of Health and Aged Care and other authorised parties.

If the My Health Record (MHR) taught us anything about the public trust with their health data, it taught us that the public tends to be either very distrustful or at best apathetic about joining in.

Prior to forcing everyone to opt in, only 1.6 million patients signed on for that data journey and when opt out was introduced, 2.5 million chose to opt out.

Why do we think we will get over 11.5 million over the line easily on consent when we have to explain the above to them, which is a lot more cross department and organisation sharing of data than the MHR?

What about getting consent from the group identified in the assessment below?

… people experiencing family and domestic violence or homelessness, more mobile populations, people who have not engaged with primary care services previously and people experiencing social disadvantage will be able to register in VPR on their first visit to a practice …

Really?

We’d be lucky to get this cohort to even darken the doors of any GP practice in numbers which would be in any way meaningful, let alone then get them to sign on to the above smorgasbord of data permissions in one session with their new GP.

Problem 5: Very bad ROI for GPs (so far)

Although we are very obviously in the early days of MyMedicare, and we need to accept that more “detail is coming” to some degree, if you break down the government’s opening offer to GPs, it feels like the usual bad deal.

Here’s the main deal so far, based a DoHAC response to questions:

- A GP will get a one-off $2000 if they sign up a hospital frequent goer (more than 10 x visiting a hospital in one year). So far there is no information on any ongoing payments other than a suggestion from the AMA that a GP might get another $500 per year if they keep that patient away from a hospital.

- This money will need to be spent on “wraparound care” somehow, presumably by using some of the money to get allied health partners to help keep that patient out of hospital.

- A GP will not have to charge a patient for an unspecified but “longer” telehealth consultation – longer than 20 minutes on the phone, perhaps – if they join, which technically is no extra money unless a GP gets a lot more patients to do a lot more longer telehealth calls. It’s hardly a compelling value proposition.

That’s pretty much it other than incentives to link aged care patients to GPs will be hooked into MyMedicare, but it’s not known how at this point of time.

There will be no MBS item for enrolling anyone who is outside of this frequent hospital goer cohort, as was originally proposed for VPE when it was being proposed for over-70-year-olds only.

Apparently (and it’s all over the OIA document) GPs will be gagging to enrol patients because it will give them better insights into the needs of their patients.

The OIA document doesn’t explain how that will happen and why.

If a GP already has a long-term patient, its wholly unclear how signing up would offer any more to a patient than the existing patient management services already on offer in a practice.

OK, so $2000 for the first 12 months at least.

Just say a GP takes this challenge on and enrols one of these pernickety frequent hospital goers and keeps them out of hospital.

What sort of saving is that for the health system and how much is the government passing on to our GP?

Well, back of envelope, someone who goes to hospital 10 times per year is costing the system easily somewhere between $50,000-$100,000 per year (eg. 10×2 days at $2500 a day at a guess – if you’re going to hospital that much you aren’t going in for a few hours every time).

So the system saves at the very least $50,000 and of that we’re going to give a GP $2000 to start and $500 for every year they succeed.

Feels a little unbalanced and unrealistic.

Let’s not forget that to earn that $2000 and $500 a GP is going to need to give 30% of it away as overhead to their practice admin, and much of the rest to allied health providers, many of whom will be charging nearly $200 an hour for their services (NDIS rates), which means the GP is probably going to have nothing left anyway.

One practice owner we spoke to said of the offering so far: “Mark Butler promised he wasn’t going to nickel and dime us any more … this is nickel and dime stuff.”

Problem 6: How do you identify frequent hospital goers and get them to a GP?

We are starting to get into some of the real nitty gritty here, but we may as well because so far no one is explaining how these problems would be resolved in MyMedicare.

How do you identify hospital frequent goers and get them back to a GP so they can enrol them in this program?

Within a practice you might ask your friendly POLAR, Primary Sense, PenCat or even Cubiko to develop some new algorithm in their software to dive into your practice data set and try and find patients who match this criteria.

It’s possible, but not easy according to one of these providers and several practice managers we talked to.

Then of course you’d have to get that patient over the line on value proposition and consent.

So far the value proposition is so thin for both the patient and the GP that it doesn’t feel like either would see a return on their time to even think about it.

Typically of course, people who go to hospital 10 times a year aren’t sitting in GP practice management data bases.

The main way the government is so far proposing to round up this troubling and expensive cohort of patients is to use the data in the public hospital networks and data match it with Medicare data to try identify any local GP they may have visited.

If they can’t do that in the hospital data easily, then they look set to use a PHN to take that data back to a GP practice and then somehow work with the practice to try to enrol them.

A lot of these people won’t have a regular GP of course. It’s the cohort most likely to never go to a GP, or when they go to one, they don’t come back to the same one.

What then?

It feels like the government might be contemplating stepping into some tricky privacy terrain at this point.

The government would have to write to that patient directly and suggest they visit a specified local GP practice (if the patient contact details are still in play) and sign up.

According to DOHAC it is planning on taking that data out state hospital networks and passing it on to PHNs to chase that patient through.

But there is some question as to whether a state government can hand that data over to PHN if there is no connection to a GP practice in the data, because that would be taking the data outside the state system and in potential breach of state based privacy legislation (public hospitals can share data freely but not easily outside the public hospital network).

It would be an interesting letter to get out of the blue from a hospital you’d visited a few times, but if you got the letter from a PHN you’d never been engaged with, you might be a little confused as to what was going on.

And what would be in a letter that would offer a patient enough value to go to the trouble anyway? Hopefully not the fluffy feelgood stuff that is in the OIA document.

So far all that is on offer for patients are promises that a GP is going to look after you really well and keep you out of hospital, and you might get longer telehealth calls.

But these patients aren’t the type to trust or use GPs much anyway and they probably have never done a telehealth call.

If you think about the degree of difficulty in this process, does anyone imagine it’s going to be smooth running?

Certainly the OIA didn’t think that DoHAC had thought all this through.

Problem 7: The technology to make MyMedicare work

One more nitty gritty thing and then we will let you go.

Detail counts when you are going to execute a program so obviously complex, so thoroughly central to sector reform and which is going to take up so much time and money, right?

The OIA report describes the technology that will underpin MyMedicare at a high level as using existing Services Australia billing platforms like PRODA and HPOS to make a GP’s life easy when enrolling a new patient.

But so far, using these platforms and integrating them with GP patient management systems to make it easy is a long way from reality.

DoHAC says the MyMedicare system uses existing digital systems managed by Services Australia including PRODA, HPOS and the Organisation Register and that the process will include:

• Practices uploading details of their business onto the Organisation Register;

• Practices linking relevant providers to that business (through the Medicare Provider Number) in the system; and

• (once open October 2023) Commencing patient registration (through a patient’s Medicare or DVA number).

Services Australia says it “will commence communications related to system use to assist practices to be ‘MyMedicare ready’ from 1 July 2023 onwards”.

But it’s unclear what “MyMedicare ready” means.

Certainly, the PMS systems practices use won’t be ready to process any MyMedicare enrolments or data.

DoHAC and the Australian Digital Health Agency have already commenced talking to software vendors about the idea of building integrations that would allow a PMS to do enrolments, talk to PRODA and then, presumably, track care.

But talking to some of those vendors, they aren’t entirely sure of what they are going to need to do and who is going to fund them to do it.

The first trial patients for MyMedicare are supposed to start in October this year.

Four months is not enough time for any of these vendors to pull off a piece of development like that and have it tested, particularly given they are still largely in the dark on requirements.

If such integration was to really be introduced the cycle for development is more like well over one year and it sounds like it won’t be cheap.

That means that whoever is in early on the MyMedicare trials isn’t going to have any technology that makes enrolment easy, and certainly the government won’t have any means of tracking the care of an enrolled patient to be able to certify any ongoing payments.

Another possible issue here: essentially the government is asking software vendors to spend a lot of time, money and effort, and trust them that MyMedicare will be the future.

If they’d done that for Health Care Homes, those vendors would have burnt a lot of money and opportunity, and the government would have burnt a lot of trust.

There are quite a few issues to overcome before there is any technology in place to make enrolment and care monitoring simple in this scheme.

A good idea poorly thought through

The concept of MyMedicare is the right concept: we need a means of building far greater continuity of care, and measurement of that care so we can start funding GPs more for outcomes with a degree of confidence that the funding isn’t being wasted.

But so far MyMedicare looks a lot more like a last-minute placeholder than a well thought out and analysed plan that GPs and technology vendors can put their faith in up front.