The move to digital healthcare management has been a long time coming, but it is happening, and GPs need to jump in

We’re great ones for predictions at The Medical Republic so here goes a couple of big ones regarding personal electronic health records and GPs.

The My Health Record system (MyHR) is finally going to do some good, but patients carrying around their personal electronic medical records (EMR) isn’t going to look anything like government agencies or doctor groups have been saying it will for a while. That’s probably a relief because no one could quite work out how the MyHR was ever really going to work if neither doctors nor patients had particularly bought into uploading and maintaining the data.

Two things are happening about the MyHR project that should be far more interesting to GPs:

- The Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) (formerly the NEHTA) is starting to cut through the murky world of pathology, radiology, pharmacy and hospital reporting to offer centralised data on the MyHR which doesn’t consist of just messily cobbled together health summaries from GPs who aren’t being paid well enough to stop and do this job properly.

- The private sector is starting to move rapidly on the mobile opportunity of personal health records and some, such as MediTracker, have cracked the problem of talking to the major patient management systems in a live, and reasonably seamless, manner.

GPs are now faced with the very real prospect of having technology which allows them, their patients, and allied network, to share a mobile patient record that is live and useful, and, most importantly, is not difficult for you or your patient to maintain.

Such technology can now serve a very immediate and practical purpose, such as help GPs to much better manage their patients’ chronic illness plans. And it isn’t going to get in the way of you and your patient, such as loading health summaries tend to do now.

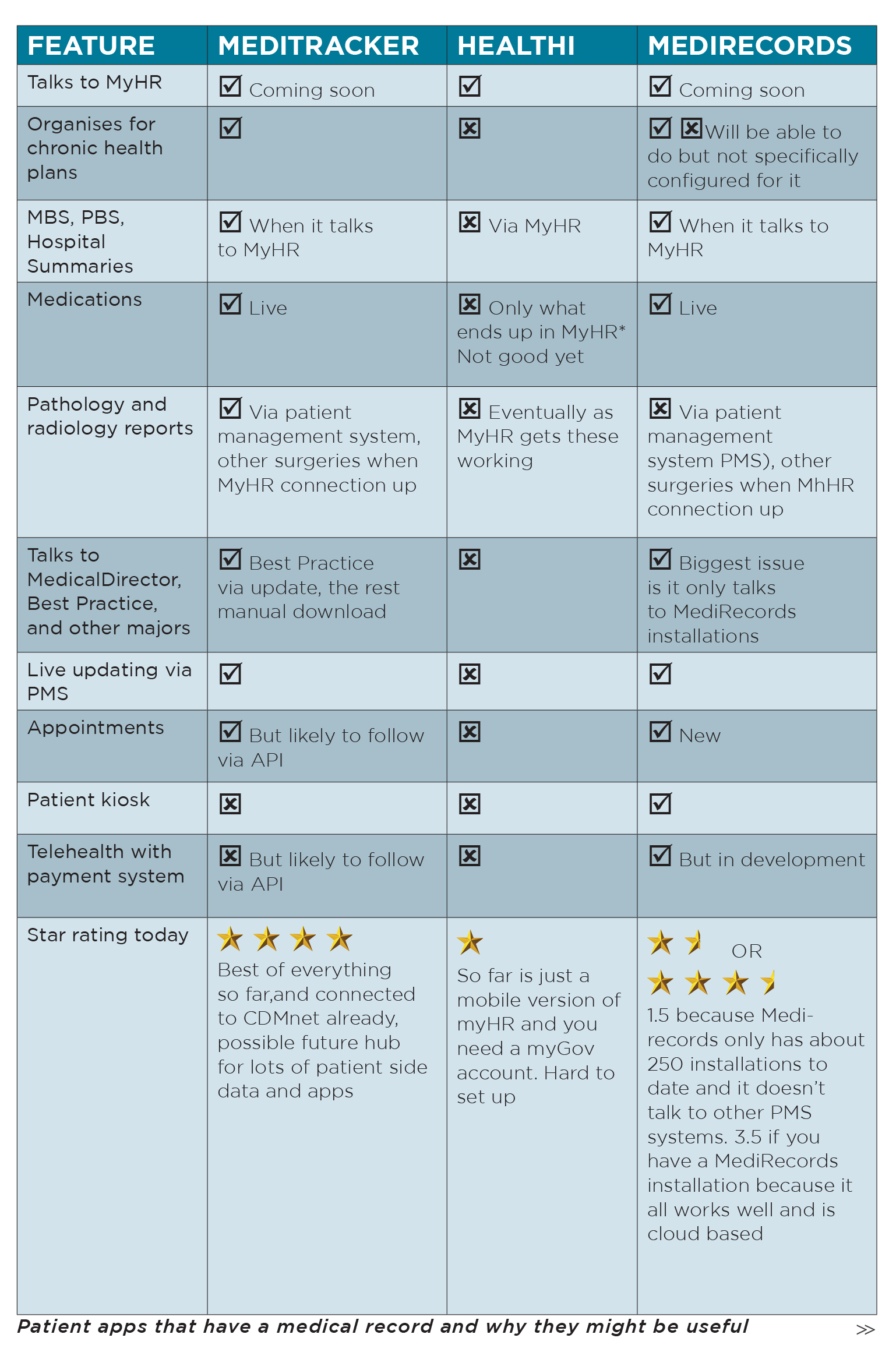

Today, only one mobile app actually talks to the MyHR, and that is Chamonix’s offering, called Healthi.

Unfortunately, Healthi is currently next to useless because it doesn’t talk to your patient management system, such as Best Practice. Plus, Healthi doesn’t appear to understand the ecosystem of GPs and allied health professionals, where the most impact from a mobile personal EMR can be achieved.

To even get the Healthi app to work you have to set up a myGov account, and if you’ve ever tried to do that, you know that it’s going to be painful to get it all going.

MediTracker, which TMR reported on in our last edition, does talk to the major patient management systems and has a cloud network that talks to allied health, specialists and hospitals. But it isn’t talking to the MyHR yet. This apparently is going to change in the very near future.

When this occurs, GPs will have a lot of what they need for the personal mobile EMR to be very useful for them and their patients and GPs should start thinking about embracing it.

Undoubtedly the people from Chamonix are thinking of talking to the major medical software systems as well. And according to Tim Kelsey, CEO of ADHA, no fewer than 30 software and mobile developers are currently working on talking to the MyHR application program interface (API) and the ADHA is itself building a MyHR app. So the race to produce a useful personal mobile EMR has well and truly started.

Part of the secret to the predicted success of “overarching MyHR” versus “agile private sector” developers, is that the ADHA appears to more adaptable to the idea that it isn’t the absolute solution, but it needs to facilitate the developing technology and delivery ecosystem in the best way possible. That’s a crucial change.

Some things can’t be solved by the private sector, and need to be provided by the government. In the case of the MyHR, the provision of central records for MBS, PBS, pathology reporting, hospital reporting and even community pharmacy data, will be invaluable to the agile mobile apps that are starting to spring up.

Professor Michael Georgieff, who developed Meditracker, acknowledges that to be both speedy and safe, MediTracker shouldn’t be handling very sensitive data, at least initially. Stuff like this can be passed back and forth with the MyHR when needed.

To succeed, all private sector apps will have to talk to both the computer desktops of doctors, especially GPs, (and maybe one day their mobile patient management systems, when they start to take off), and the centralised MyHR.

The problem with the MyHR by itself is that it is cumbersome and slow by the very nature of all that additional, sensitive and important data it is seeking to centralise. It doesn’t poll live data from doctors and patients, and it probably shouldn’t ever try.

The MyHR couldn’t succeed by itself because it wasn’t useful in this form. Doctors had to be incentivised with ePIP to upload health summaries and, even then, it was a chore. There wasn’t a connection for doctors to immediate patient wellbeing. The mobile apps, however, solve this issue.

But GPs aren’t going to do the hard yards of solving the various secure reporting issues that occur in pathology and radiology reporting. That’s another job for the government.

A big secret is how flexible and adaptable the ADHA is showing itself to be. Instead of “pursuing the dream of one source of all truths”, Tim Kelsey says that the job of the group is to facilitate other providers who are solving problems at the coalface, and to integrate with this fast-evolving ecosystem and stay adaptable.

One of those providers looks very much like it will be MediTracker, at least today.

MediTracker has as its goal the very practical idea of connecting GPs with all the component parts of managing their patient’s chronic health condition. It’s useful to the GP and the patient, and neither really has to do a lot because the app is doing much of the data work automatically. All the patient really has to do is take their medications and turn up for their allied health appointments when their mobile pings them to do it.

So GPs are very likely to see apps such as MediTracker as their friend – someone who integrates with their workflow relatively seamlessly, does not ask for too much boring and unpaid side work, and most importantly, has the potential to significantly improve the outcomes for their patients.

MediTracker wasn’t developed to be the Holy Grail. But if it ends up connecting many patients to their surgeries, then we are going to see happen what we’ve seen happen, spectacularly, in other disrupted digital markets. That is, a network effect.

Popular examples of “network effect” are Microsoft Office, Google and Facebook. It is where one product proves so useful it becomes a distribution hub for a market. When that occurs, more and more services must aggregate to the hub. As more and more distribution occurs via the hub, it becomes more and more useful to users, and so on. Eventually, competitors fall off and you end up with a form of monopoly, such as Google has in the search market, Microsoft has in office software and Facebook has in social media.

Eventually that’s a problem, but for now, this is a problem we’d love to be looking at one day in healthcare.

In the case of MediTracker or its likely competitors, the potential is for one app to sit in a patient’s pocket that does most of what you really need, health-wise. You can see that if MediTracker gets market share quickly then appointment engines, telehealth providers, and so, on will want to sit on that distribution platform.

And if MediTracker doesn’t cut it, there at least 30 other companies hot on its heels which are currently trying to talk to the MyHR. None of those is likely to succeed if it does not also talk effectively to GPs, like MediTracker does.

The take-home message here is that we are almost definitely at the start a paradigm shift in how we do healthcare. Both patients and GPs are going to be empowered with a lot more of their own information available at their fingertips.

GPs are the natural fulcrum of this shift.

But GPs can be slow in embracing stuff like this, not because they are digital laggards, but because they are so patient-focussed and busy they don’t stop to take in changes such as this. Hopefully most GPs will see these changes for what they are and the potential they represent for the profession to fly higher as the hub of healthcare management.

This change has been a long time coming, but it’s happening now, and GPs need to jump in.