Drones are now delivering life-saving blood supplies in some developing nations. How could we use them here?

Heavy rain in Rwanda can carry a death sentence for people in urgent need of a blood transfusion.

The motorcycle-based supply chain, which usually transports blood products from cities to rural areas, breaks down once the roads become flooded. This poor infrastructure means a pregnant woman in Rwanda is most likely to die from postpartum hemorrhaging than any other complication.

While Rwanda is far from being a rich nation, it is a world leader in one particular innovation that could leapfrog its health system into the future.

Once or twice a day in the country’s Muhanga region, Rwandans who look skywards will see a drone quietly passing overhead. The aircraft fly automatically from a distribution centre to rural hospitals across the western half of the country.

The drones carry packed red blood cells, plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitated AHF, and Rho(D) immune globulin.

“[Rwandans] call them ‘sky ambulances’,” a spokesperson at Zipline, the California-based company that designed and operated the drones, said.

The best-case scenario for a Rwandan patient in the Muhanga region in need of a blood transfusion is a four-hour delay, although they can often wait much longer. “With Zipline you are looking at cutting that four hours to something like 15 minutes,” Jean Philbert Nsengimana, the Rwandan Minister of Youth, said.

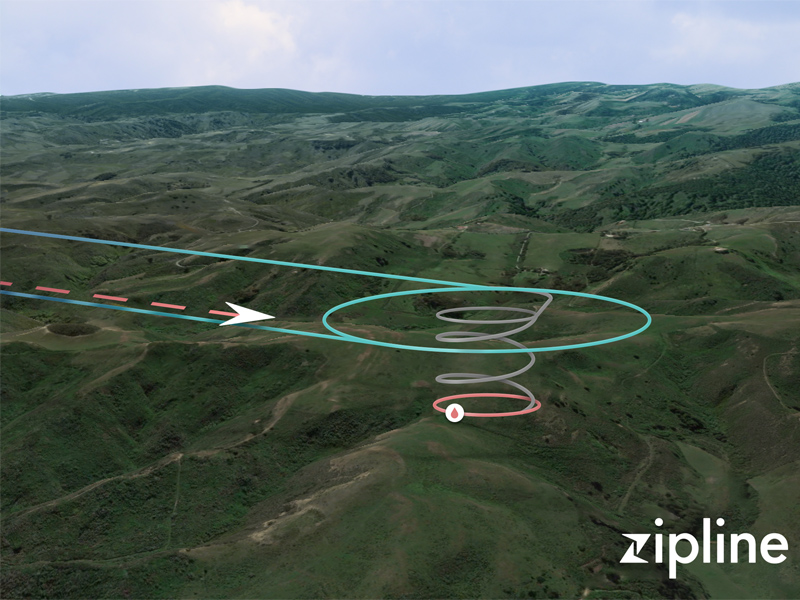

Zipline’s drones are launched by catapult and use satellite navigation to carry a 1.5-kilogram payload a distance of up to 75km.

With twin electric motors and a more than two-metre wingspan, these aircraft can operate in strong winds. The drones do not land at the delivery location, dropping packages suspended from paper parachutes mid-flight before returning to their launch location. A text message alerts the hospital two minutes before arrival. Eventually, Zipline will oversee 50-150 of these flights per day.

Roads are a seasonal luxury in many parts of the developing world. According to the African Infrastructure Knowledge Program, only one-third of Africans live close to a road that functions all year round. This causes what is known as the “last-mile problem”, where rural communities are cut off from the medical supplies in urban centres.

In Malawi – a country with an HIV prevalence of 10% – people can wait up to eight weeks for HIV test results. Samples are usually transported by motorbike, which requires a large load to be cost-effective. Drones could speed up diagnosis and increase early enrollment in anti-retroviral treatment.

UNICEF is trialling the use of drones to transport dried blood samples from rural clinics to specialist laboratories for HIV testing.

A pilot program was launched last year in partnership with US-based drone company Matternet. In April, the Malawi government plans to open a 40km flight corridor for the private sector to explore the use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.

The low air traffic, minimal red tape and real need for transport systems in developing countries makes them ideal for medical drones.

On the downside, the drones can be regarded with suspicion by locals who associate them with surveillance and military activity rather than humanitarian missions. They are also vulnerable to theft.

In Australia, the challenges are different, but no less daunting. Here, we have tight restrictions on the use of drones in urban areas. The aircraft generally cannot legally go beyond the line of sight of the operator nor fly over densely populated areas – both essential elements in a medical drone system.

Despite this, one group is pressing ahead with Australia’s first medical drone trial, to be conducted in Sydney later this year. The RPAS Consortium (comprising corporates and universities) is meeting with the Civil Aviation Safety Authority in March to finalise approval for the “Angel Drone” trial flight.

The group has been testing the drone in Camden in NSW to address safety issues.

“We’ll show that we’ve got safety devices … (so) if we lose contact, or with the loss of one engine, that it can still maintain height and won’t fall onto a busy Anzac Parade,” consortium president and aviation lawyer Ron Bartsch told TMR.

If all goes to plan, an Aerolens multi-rotor drone will carry incubated blood plasma from the Prince of Wales Hospital, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs, to a nearby sports oval at the University of NSW. “Even though it’s a short distance, it’s very significant in what it is achieving,” Mr Bartsch said.

The consortium is also partnering with aeromedical charity CareFlight in the Northern Territory to investigate integrating drones into the health system.

The airspace was less congested in the territory so the location lent itself to drone trials, Mr Bartsch said.

Even though it’s a short distance, it’s very significant in what it is achieving.

Other creative uses for drones in the Top End include placing landing lights for planes or amplifying a radio signal to assist emergency services to communicate with injured people.