And this was only the pilot program.

Newborn genomic screening has the potential to become one of the country’s most effective public health interventions, say Australian experts.

Adding full genomic screening to the standard newborn heel-prick screening could catch hundreds more childhood diseases and potentially save more lives.

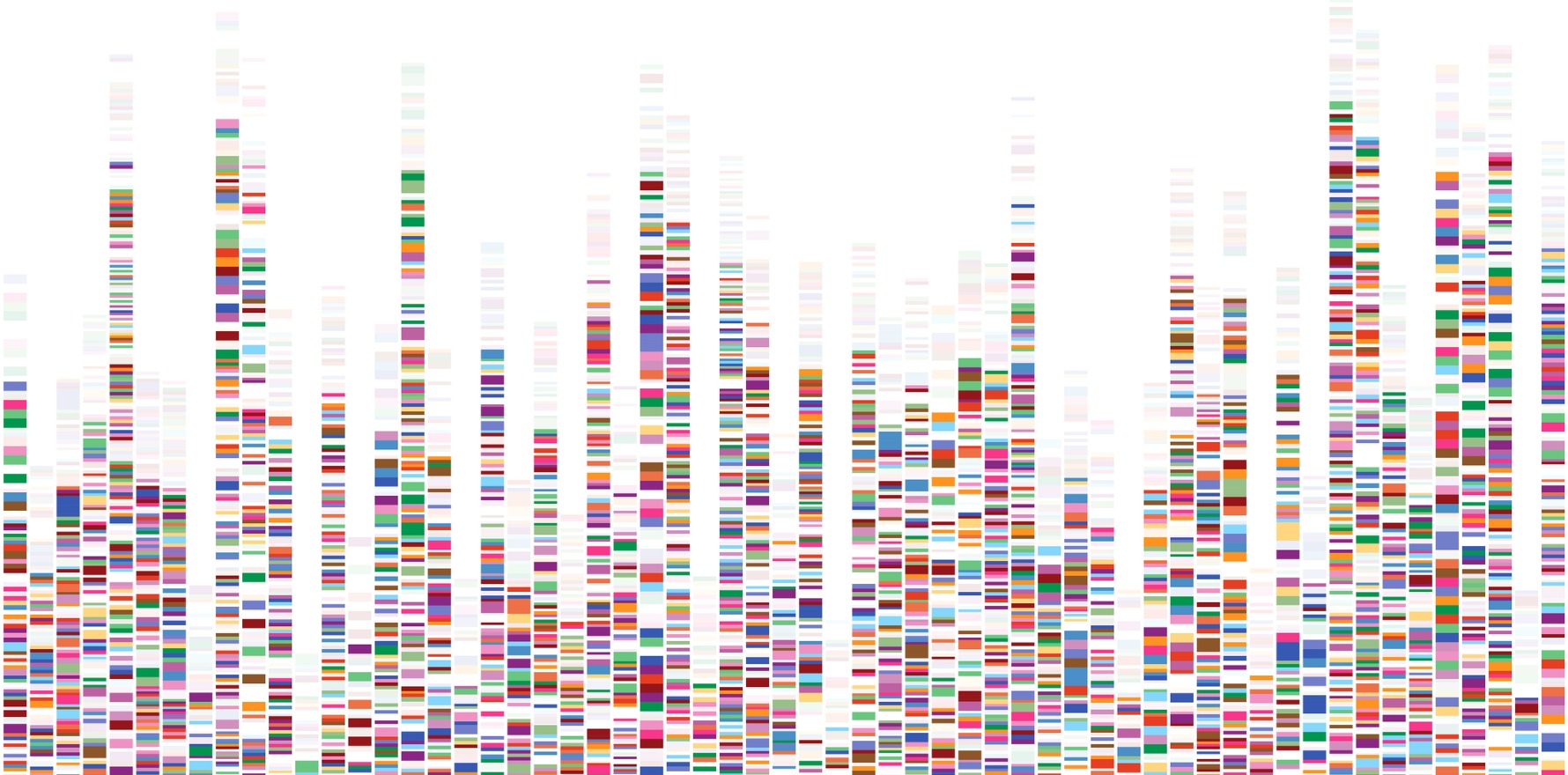

The BabyScreen+ study screened 1000 newborns in Victoria for more than 600 genes associated with early-onset, treatable childhood conditions.

This included conditions that do not have known biochemical markers, such as those which predispose infants to childhood cancers.

Of the 16 babies who received a high-chance result, only one of them was detected via standard newborn screening (NBS), which was a case of hypothyroidism.

For the 2% who had a high-chance result, preventative measures, surveillance, active management or immediate treatment were able to be implemented early.

For one infant, genomic screening led to the diagnosis of a rare and severe immunodeficiency disorder, which allowed for early intervention and the commencement of immune modulator therapy.

They were also able to proactively plan for bone marrow transplantation, which was successfully performed when the infant was four months old.

Some relatives were also advised of potential risk from the results of the newborn genetic screening.

Following subsequent cascade testing, 12 parents and eight siblings were diagnosed, none of whom were previously suspected of having any genetic conditions.

The results from this and other international studies published this year now total more than 10,000 babies, Professor Zornitza Stark, clinical geneticist and co-lead of the Translational Genomics Research Group at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, told The Medical Republic.

“We have all demonstrated feasibility and impact. The technology stands to transform newborn screening programs,” she said.

The automated system showed a sensitivity above 97%, with no false positives and only one false negative.

In that case, a multinucleotide variant was misclassified as two lower-impact variants, an issue the researchers said reflects a known limitation of the software.

All high-chance findings were confirmed by orthogonal testing on fresh samples.

DNA sequencing results are highly accurate, and Professor Stark said the team was not surprised that all the results were confirmed.

“For recessive conditions, a small number of false negative results can be expected as the two variants may turn out to both be inherited from one parent, and therefore not result in disease,” said Professor Stark.

“Whether or not it is feasible to use the existing blood collected for standard NBS was a key part of our research.”

They found that they were able to extract sufficient DNA of high quality from the existing blood and perform whole genome sequencing in 97% cases, with only 3% requiring a recollect.

Excluding samples that required re-extraction would have led to two missed high-chance results.

The parents and guardians survey

Of the almost 1000 respondents, 80% indicated that they consented to the testing immediately and easily.

Less than a tenth found it to be a difficult decision.

Nearly 80% of respondents were most strongly influenced to undergo the newborn screening by a desire to know what to expect for their child’s future.

Of the 10 surveyed who had declined the screening for their newborns, eight reported the main influence for their decision to be concern about potential negative impacts on parents due to the results.

Older parents were more likely to choose the screening; those aged 30 years and over were around 2.5 times more likely to consent, with likelihood increasing for those aged 35 years and above.

Related

Parents who received a low-chance result reported positive feelings of reassurance.

Those interviewed who had a high-chance result reported valuing the clinical utility of results, such as prompt genetic counselling and access to high-quality information.

The majority (80%) would choose to have the genetic screening for a future baby, and 92% would recommend it to family.

All but one respondent thought genomic newborn screening should be available to all parents, and 97% thought it should be publicly funded.

The barriers

Genetic disorders were caught early and additionally discovered in family members, parents and caregivers were overall happy with the testing and it can be completed using existing collection processes.

So, what’s the hold up?

“This is a costly and complex technology, and we need to make sure we have robust evidence of benefit and of cost-effectiveness before routine adoption,” said Professor Stark.

She explained that substantial investment would be required to implement genomic screening, both to generate the evidence required at scale and to build the national infrastructure.

“We will require additional sequencing and compute infrastructure as well substantial workforce expansion to both provide high quality test interpretation as well as manage the results, support families and provide downstream healthcare across a wide range of rare conditions,” she said.

One of the key challenges would be how to scale genomic NBS for all 300,000 infants born in Australia every year and reduce the need for manual review, she explained.

She said the study was an opportunity for the team to learn how to do this. They were able to improve processes and reduced average failure rates from 28% initially to less than 5%.

Around half of the low-chance results required manual review due to certain variants the algorithm could not automatically interpret, but the team identified changes that would reduce this to 20%.

“We will also need to ensure national consistency and make sure Australian babies and families benefit equitably, including those from Indigenous and other traditionally disadvantaged communities,” she said.

“In addition to the practical challenges, a number of ethical issues surrounding consent models, data storage, privacy and reuse will need to be resolved by trialling out different solutions and carefully assessing the associated benefits and risks.”

“Realistically, it will take another 10 years of large-scale research nationally and internationally before genomic newborn screening could be incorporated into standard practice.”