Understanding pelvic pain might reduce reliance on surgical procedures that don’t outperform non-surgical management.

Persistent pelvic pain – which is estimated to cost the Australian economy approximately $10 billion each year – has received a lot of media attention in recent times, largely on the back of increased focus around improving the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis.

While these efforts are welcomed, there is much more to pelvic pain than endometriosis.

A free paper session at the recent Australian Pain Society Annual Scientific Meeting, held in Darwin, put a spotlight on some of the big issues in how patients think about – and how clinicians manage – persistent pelvic pain.

What do women think about persistent pelvic pain?

Ms Grace Ferencz, from the University of South Australia, said understanding women’s causal beliefs about their persistent pelvic pain was important as they directly impacted pain intensity and functional ability.

From a review of 23 studies, Ms Ferencz identified four key themes:

- It’s happening to me because I’m a woman.

- It’s happening to me inside my body.

- It’s happening to me due to my actions and behaviours.

- It’s happening to me due to my life experiences.

The first theme reflected how women (and men) rationalised and dismissed pelvic pain as something that was “normal for women” or something they didn’t have a choice about.

“That meant [women] felt quite disempowered in the pain management [setting] and felt that they didn’t have access to healthcare services, because they didn’t have a valid condition that warranted treatment,” Ms Ferencz explained.

The second theme reflected a common misconception about pain – that it was due to a sinister pathology, even when no healthcare professional had ever been able to match their symptoms with a diagnosis.

The final two themes involved women attributing, or blaming, their pain on specific past events or behaviours, such as being bad at sex, childbirth or traumatic experiences.

“Women began to notice that things they did had impact on their pain for better or worse, and some women began to use this [to their advantage],” said Ms Ferencz, citing examples of women associating pain flares with being stressed or run down, which allowed them to change their behaviour to reduce painful flares.

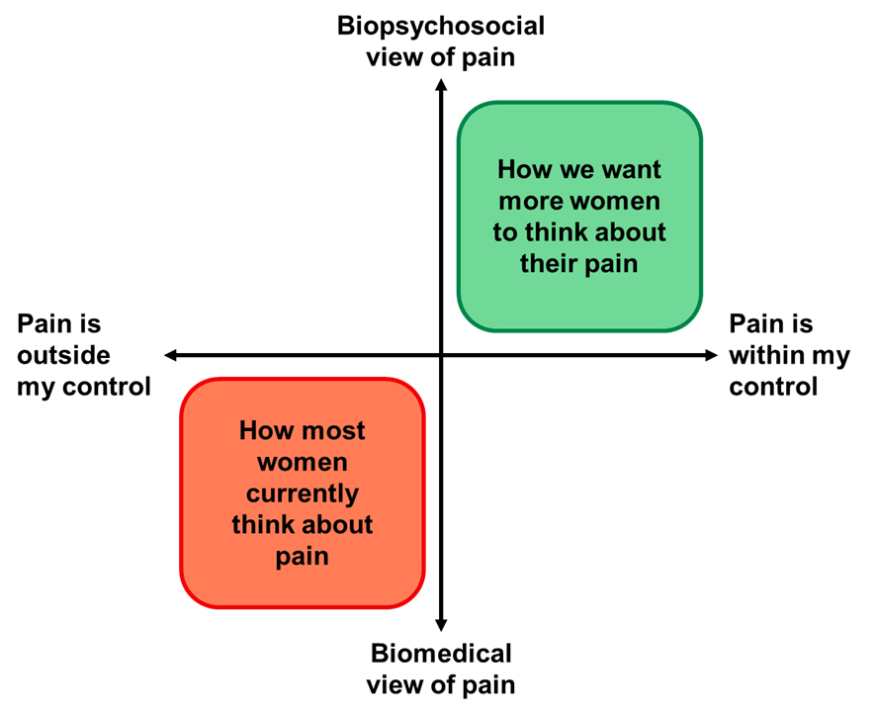

The combination of these themes resulted in most women believing their pain was due to biomedical causes outside of their control, which was the opposite of what Ms Ferencz and other healthcare professionals wanted.

Ms Ferencz said understanding and shifting beliefs about persistent pelvic pain could go a long way to helping find the right treatment for the patient.

“This is important clinically, because we know that if we look at women’s belief frameworks, we can specifically tailor their pain rehabilitation, [which can] empower women to feel more in control over their pain management and their lives.”

Related

Is surgery the answer for persistent pelvic pain?

Dr Samantha Mooney, a Melbourne-based obstetrician and gynaecologist, shared the results of The Persistent Pelvic Pain study, which aimed to explore factors influencing long-term outcomes in women with persistent pelvic pain.

As part of the study, Dr Mooney and her team randomly referred 471 women aged 18-50 years with persistent pelvic pain to one of two clinics within their tertiary hospital. One clinic tended to treat persistent pain with surgery, while the other more commonly opted for non-surgical management. Patients were followed up every six months for three years.

Patients who received non-surgical management had non-inferior outcomes across all measures, including various aspects of pelvic pain (e.g., dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea and painful bowel movements), quality of life, sexual functioning and pain catastrophising.

One in five patients underwent a laparoscopy ― 29% of patients at the surgery-favouring clinic versus 13% at the other clinic. A similar proportion of patients were diagnosed with endometriosis across the two clinics, but 49% of patients who underwent a laparoscopy or laparotomy had no visible signs of endometriosis.

A subgroup analysis of patients who underwent a laparoscopy or laparotomy revealed patients without evidence of endometriosis had decreased dysmenorrhoea symptoms compared to patients with signs of endometriosis at the three-year mark. There were no differences in other pain scores, quality of life or pain catastrophising.

The study was limited by a poor response rate (34% completed the three-year follow up).

“Each laparoscopy in Australia costs over $6000. More than 50% of people will have a repeat operation within five years,” Dr Mooney told delegates.

“[But] long-term quality-of-life outcomes may not be improved with surgical interventions for all comers with persistent pelvic pain. Our patients need to be assisted to understand the true lack of evidence of long-term symptom control and quality-of-life improvement with surgical interventions.”