Liraglutide might help take the weight off quickly, but adding exercise is better for long-lasting results.

“Give a man liraglutide and you make him healthy for a year. Teach a man to exercise and you make him healthy for a lifetime” – ancient Chinese proverb.

GLP-1 receptor agonists such as Ozempic (semaglutide) and Saxenda (liraglutide) have gained incredible popularity for their use as anti-obesity drugs, yet little is known about their long-term effectiveness and whether any potential weight loss can be maintained once someone stops taking them.

Now, a new study published in eClinicalMedicine shows body weight and composition (body fat) are better maintained 12 months after completing a supervised exercise program compared to 12 months after stopping liraglutide treatment.

The new research was a post-treatment extension of a previous Danish RCT that investigated changes in body weight and body composition in obese adults (initial BMI 32-43).

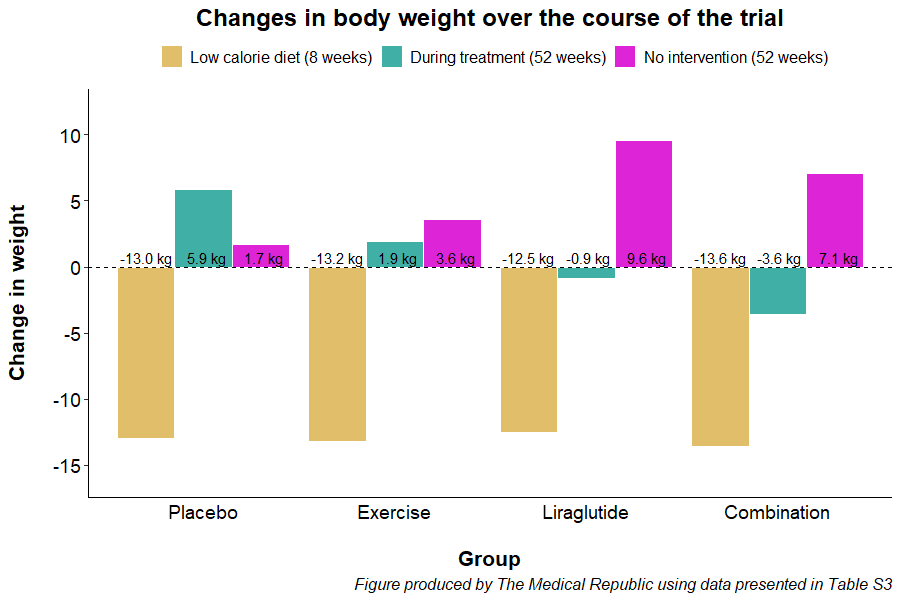

The trial started with an eight-week low-calorie diet phase (800 kcal/day). Only participants who lost at least 5% of their initial body weight were randomised to one of four treatments for the next 12-months: daily liraglutide injections (0.6 to 3.0 mg per day, depending on what dose could be tolerated), a supervised exercise program, a combination of exercise and liraglutide, and placebo. Participants were then followed up 12-months after completing their year long randomisation (i.e., two years after they first started).

Related

All participants lost a similar amount of weight prior to randomisation. Participants in the placebo and exercise group regained weight during the year-long intervention phase, while participants in the liraglutide and combination treatment groups lost weight during the first 12 months.

However, all participants gained weight during the 12-month period after they had stopped treatment. The liraglutide and combination treatment groups put more weight back on in the year where participants were left to their own devices compared to patients who had previously received placebo or exercise alone.

“Weight regain during the one-year post-treatment phase was 6 kg larger for participants who had previously received liraglutide alone compared with participants who had previously received supervised exercise alone,” the researchers wrote.

A similar trend was observed for changes in body fat percentage, with the participants previously randomised to liraglutide (average change 2.7%) and the combination treatment (2.3%) having larger increases compared to patients who received placebo (-0.3%) or completed exercise alone (1.4%).

Associate Professor Priya Sumithran, an endocrinologist and head of the obesity and metabolic medicine group in the department of surgery at Monash University, said the findings were important, even if they weren’t necessarily surprising.

“The results are entirely consistent with what we would expect – all groups put weight back on after stopping a structured weight loss program, and exercise was important in helping improve the maintenance of weight loss.”

Professor Sumithran felt it was unfair to say the liraglutide group performed worse than the exercise only group.

“I think the benefits were similar in both groups,” she told TMR. “The exercise only group maintained their weight loss through the intervention and then regained it slowly, whereas the liraglutide group lost a bit more weight but put it back on [once they stopped taking the drug].

Researchers noted patients who were prescribed exercise were more physically active during the non-treatment period. Participants previously prescribed exercise, either alone (median 240 minutes/week) or in combination with liraglutide (225 minutes/week), also self-reported being more physically active compared to patients who received the placebo (150 minutes/week) or liraglutide alone (30 minutes/week).

“People randomised to exercise may have acquired exercise behaviours during the intervention, and therefore, were able to sustain higher physical activity levels after medication was stopped to minimise the otherwise insistent weight gain,” the researchers wrote.

Professor Sumithran agreed with the researchers conclusion that using both exercise and pharmacotherapy may be more effective for long-term weight loss and maintenance, but highlighted the results may not apply to everyone.

“It was a fairly narrow BMI range and they had no major medical problems, so we can’t know what this means for people who, for example, wouldn’t be able to do the level of exercise the researchers delivered as part of the study.”