Things are grim in general practice and it’s often registrars who suffer. But with some boundaries, it can be better.

I woke up recently to an anonymous post by a GP trainee posted in a support group of doctors (not just GPs).

I have her consent to share some of what she said.

“I’ve just finished a year of GP training – the worst year of my life. I wanted to share … to explain why GP training numbers are undersubscribed,” she wrote.

Among her points:

- Ungrateful, demanding, entitled patients are a frequent occurrence, as is threatening behaviour.

- Patients bring a laundry list of random complaints and expect them to be resolved in 10 minutes – “and oh, can you bulk bill me today, doctor?”

- She has to work from home when she’s ill, because “we have limited sick leave and if my training hours dip too low, I won’t be eligible to sit exams in July”. Yet practice staff were annoyed she was doing telehealth because they had to call booked patients to let them know. “We are just working machines as registrars with no intrinsic value as people.”

- She is the breadwinner of her family but has taken a 60% pay cut to specialise in general practice; they live paycheck to paycheck in part to save for exams, which cost around $10,000. “I am earning significantly less but I am doing more than triple the amount of work daily that I used to do in hospitals, so burnout levels are much higher for less pay.”

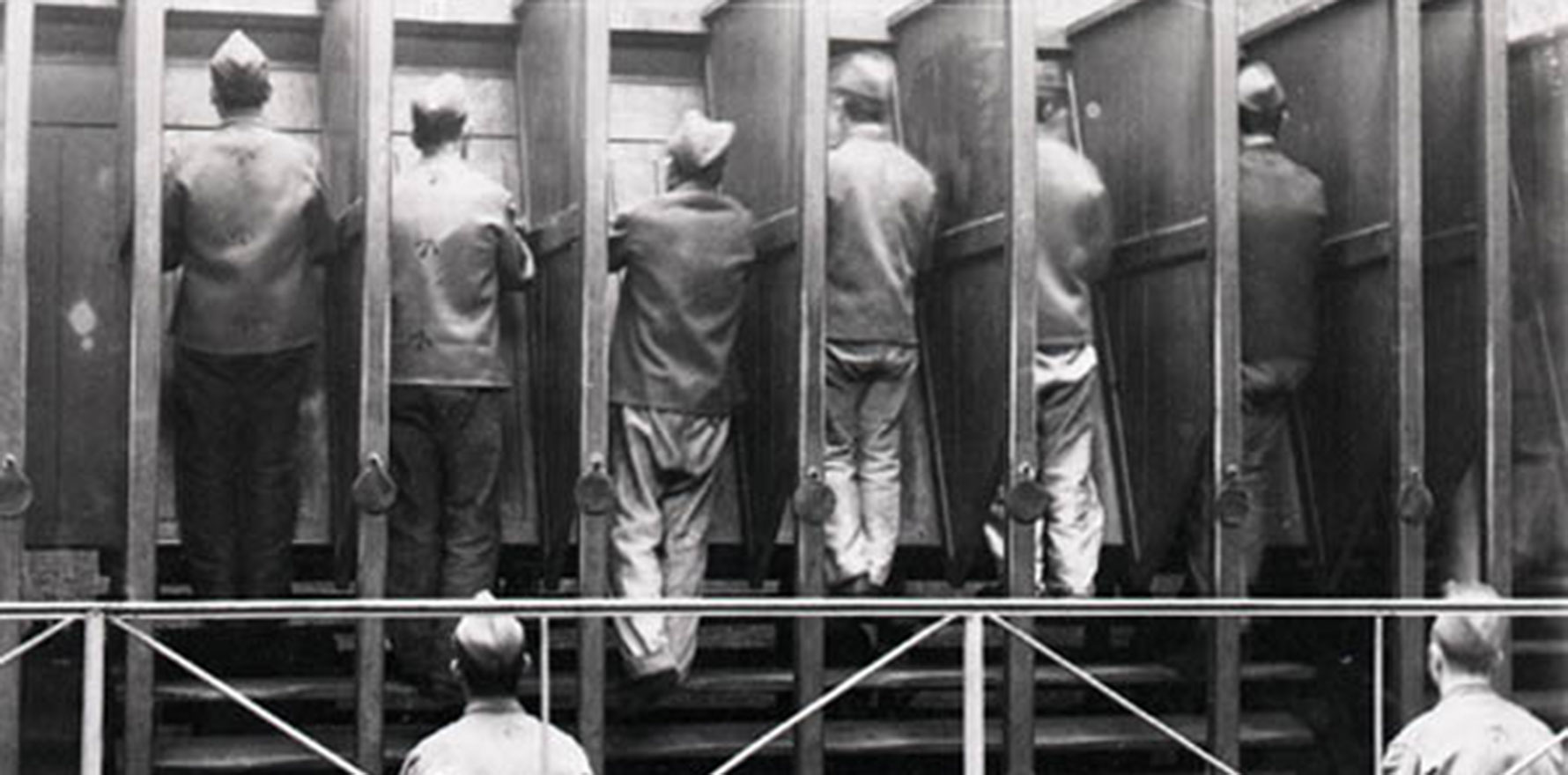

- General practice is lonely: “You are stuck in a room all day with your patients. Not much interaction with colleagues … no team to discuss cases with or double check things. I eat lunch alone … as other doctors are too busy to even get a reasonable lunch break.”

- Preparing for exams is lonely, with little socialising and limited time to study because of work and childminding.

- The sedentary lifestyle has seen her put on 10kg in a year.

She ends with “I used to want to be a GP. But now I just want to pass my exams and get out.”

When I last looked, there was over 130 comments to this doctor, most from GPs either encouraging her to push through and then to seek greener options including working in more supportive clinics and charging appropriately, or who’d had similar experiences and left general practice years ago for salaried roles and although they miss it cannot stomach the thought of returning.

Such is the state of our speciality.

So far so gloomy. On the other hand, once we have followed and moved to gap fees, most of us have rapidly found that it acts as a buffer against some of the worst behaved patients, and that most other patients are grateful for our care and help.

My comment to this registrar – as it is to every person who wants to do general practice – is this: Do not be afraid to say no. Do not be afraid to charge appropriately for your time. Let people decide if they will engage with you within the fence you erect for your safety and theirs, your sanity and your medicolegal backup.

In my experience, sadly, 80% of headaches are due to the 20% of people who are difficult, for any number of reasons, and if they are adults and not in an immediately life-threatening emergency, it is not on any of us to tolerate abuse, disrespect or other unacceptable behaviour.

For far too long in medicine we have been taught to be doormats to the whims and fancies of everyone else, from patients to difficult and demanding bosses and registrars. Often, as we climb the ranks ourselves in hospital, instead of doing better, many of us become like these people – but over the past few years, things have been slowly changing.

Many of us are speaking up, saying no, pushing back. It’s not OK to work unpaid. It’s not OK to take up someone’s time and not pay for it. It’s not OK to agree to a fee and then ask to be bulk billed.

I know that many of the public will disagree, as they did last year when I wrote about it and was doxxed on Twitter. This is not about kindness, this is about boundaries.

When we fail to care for our trainees, because we are under the pump trying to see enough patients to keep the practice open, it’s our trainees who suffer.

This registrar I’ve quoted is not the only one, and this is not new. This has been the case for at least the decade since I entered GP training in 2012, and in my many years as a clinical training visit supervisor. I would sit in on trainees at their clinics for three hours and speak to their supervisors, who would often complain the young doctors were too slow and didn’t see enough patients. Others didn’t provide as much teaching as they’d been contracted to. Yet others were difficult. With the trainees’ consent, I advocated for them to the training organisation because we all know how hard that can be.

I’ve also met non-GP colleagues who left GP training because of experiences like the one above – left in a room all day to see patients, feeling immensely out of their depth, and unable to ask for help because their supervisor was too busy seeing their own patients or would get annoyed with them.

Health Minister Mark Butler told The Guardian recently: “We’ve got to get away from this idea that general practice is somehow a B grade.” He also acknowledged the “pay gap between general practice and other specialists” and the “other conditions of employment that particularly public hospital employees enjoy that you don’t get particularly while you’re training (to be a GP)”.

It seems inane to me that no one is connecting the dots, especially Mr Butler.

A huge part of job satisfaction is being safe and comfortable in other areas of our life. When a trainee is living hand to mouth because they are forced to bulk bill everyone, it does not matter if their patients are grateful or entitled. Especially when they can’t even earn enough to pay the $10,000 exam fees to become a fellow so they can … continue to live hand to mouth.

Who signs up for that?

We all know training for ANY speciality is hard, and thankless. We get abused, we get worked to the bone. And at the same time, there are perks: the camaraderie of a team; a living wage and extra money for working overtime if we choose to; a hierarchy of seniority so we can ask for help and ideas; a supervisor who is paid, in part, to mentor and train us.

In general practice, this is far too often not the case. There are excellent practices where supervisors run at a loss themselves in order to mentor and teach trainees, but these are not the ones I’m taking issue with, nor the ones I raised concerns about in my years as a visiting supervisor.

When talking money is hard, or not taught at all, and patients are either all complex and very needy or entitled and ungrateful, every single day can be steeped in regret, and general practice can feel like the worst mistake of your life. It’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel, post FRACGP, when we can move, leave for a nicer practice.

Yet with the immense shortage upon us, it will be a service provider’s market soon enough, if it is not already, and most of us who hang in there, and learn to talk about money, and provide services that people value and are willing to pay for, will have a wonderful career. This is what many of us have also discovered post fellowship if we have dared to leave universal bulk billing.

For trainees now, however, with untenable conditions put upon them by clinics desperate to hang on to universal bulk billing, and colleges that do not care how eye-watering their exam fees are despite how little trainees earn, “hanging in there” may not be an option.