A swimmer is vomiting and in pain and has ‘a sense of impending doom’. What do you do?

We are now in the throes of jellyfish season, and the annual media stories on jellyfish stings are floating in.

Jellyfish medicine is a fascinating topic, in part because the relative dearth of literature means that much remains unknown. Allow me to illuminate what is currently understood.

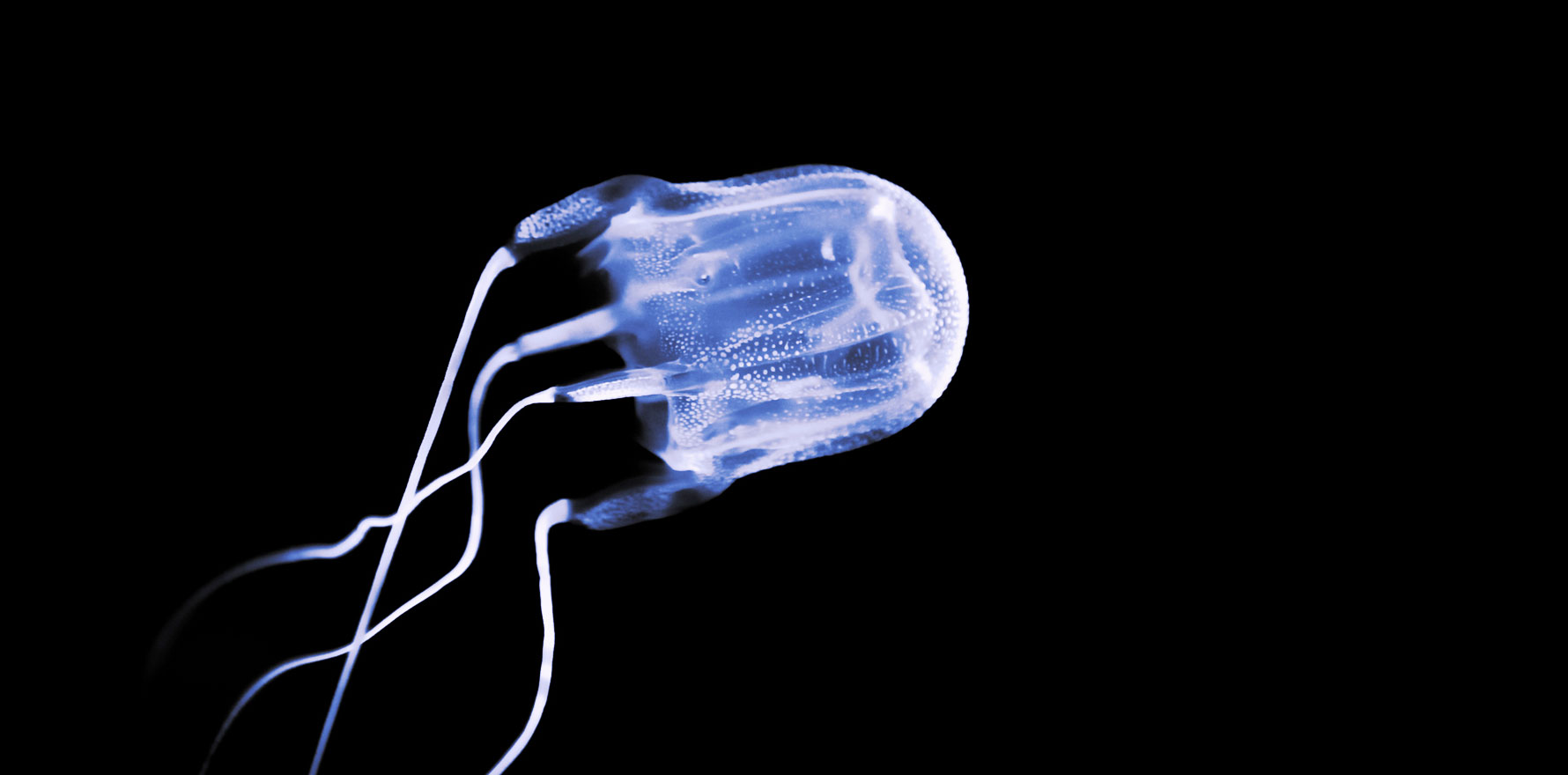

Jellyfish envenomation is the most common marine sting type. There are about 2000 known jellyfish species worldwide, and at least half of these can be found drifting in Australian waters.

How jellyfish sting

Jellyfish tentacles have thousands of stinging cells, each of which contain a nematocyst – a specialised structure containing a stinging barb that releases toxins. When hair triggers on the tentacles brush up against a predator or prey, the barbs are released.

The response in a human is dependent upon the number of nematocysts fired and the amount and composition of the toxin. In the case of the Australian box jellyfish, for instance, hundreds of millions of nematocysts are released per sting.

Types of stinging jellyfish

Australian box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri)

The Australian box jellyfish is the world’s most venomous marine creature. It has caused at least 70 deaths in Australian waters since records began in the 1800s, the most recent occurring in Mackay in 2022.

Because of their lower body mass, children are the most vulnerable. All 14 deaths that have occurred from box jellyfish in the Top End since 1975, for instance, have been children.

Its stings usually cause severe pain and linear welts. There is a poor understanding of the venom’s mechanism of action, but it is thought to be haemolytic and ionophoric, and it triggers rapid cardiovascular collapse.

Vinegar is advised in the hospital setting to prevent the discharge of any remaining nematocysts, though the validity of this practice has been questioned. Intravenous opioids are given for pain.

If an arrest is going to occur, it will usually happen within five minutes of being stung. In addition to prolonged CPR (and continuing is important), undiluted box jellyfish antivenom should be given (and possibly intravenous magnesium), though there is no consensus on how much antivenom is required. Haemodynamic instability and severe pain are other indications for antivenom.

C. fleckeri antivenom is the only jellyfish antivenom manufactured worldwide and has been in use since 1970 (first produced in Australia, by CSL). It has a risk of anaphylaxis and serum sickness. The clinical value of this antivenom is debated due to inefficacy in in vivo findings. It is ineffective against other jellyfish stings.

Irukandji (Carukia barnesi)

Irukandji syndrome is the name of the condition caused by irukandji and other jellyfish species (most of which are currently unknown, though it’s suspected that up to 25 different species cause this syndrome).

Irukandji is an anglicised version of the name of the Traditional Owners of the land on which the syndrome was first reported in the 1950s (the Yirrganydji people in Far North Queensland).

It was in 1961 that the jellyfish was proven to be the cause of the syndrome, when innovative Cairns physician Dr Jack Barnes (after whom C. barnesi is named) conducted research in which he stung himself, his son, and a local lifeguard with it, all of whom became sick (don’t worry, they all lived!).

Irukandji syndrome has been responsible for two confirmed deaths in Australia. However, this is likely an underestimate, as the absence of welts and specific findings on a postmortem would lead to misattribution of cause of death (for instance, drowning or cardiac arrest).

Symptoms include vomiting, dyspnoea, severe abdominal and back pain, profuse sweating, anxiety, headache, distress, and a feeling of impending doom. The symptoms are delayed after the sting, arising five to 60 minutes later. Welts are usually not present. It can cause cardiomyopathy, severe hypertension, acute pulmonary oedema, and, rarely, intracerebral haemorrhage.

The elusive nature of these jellyfish means that the mechanisms behind this illness remain unknown, but it is thought to be at least partly secondary to excessive catecholamine release.

Irukandji syndrome requires supportive care, largely in the form of opioids, antiemetics, and possibly intravenous glyceryl trinitrate (for blood pressure control) and intravenous magnesium (which is believed to suppress catecholamine release and mitigate pain, though its efficacy is questionable). Vinegar is also given in hospital, as with box jellyfish.

Antivenom does not exist and is unlikely to be produced given the number of different (and currently unknown) jellyfish involved.

Bluebottles (physalia)

Found across the country, though largely in southern Australia, these jellyfish do not cause systemic envenomation and, while they can cause immediate severe pain, it usually resolves within the hour. They require hot water, pain relief and time. Antivenom for bluebottles – aka man-o’-war – does not exist.

A slippery customer

Jellyfish research (both medical and ecological) is stymied by lack of funding nationally and internationally.

The nature of the research also presents numerous challenges. For instance, isolating pure venom from jellyfish tentacles is challenging due to their anatomy, which leads to lack of standardisation of venom extraction. Real-world trials of stinging are logistically difficult for many reasons. Also, many species (such as those that cause Irukandji syndrome) are simply unknown, with new species continually discovered.

Clearly, we have much to learn. But from what we currently understand, this is the official recommended first aid approach for stings in tropical and non-tropical Australia. And if you’re wondering where exactly the demarcation is between the two areas, then you’re out of luck, because this is yet another area of uncertainty. We do know that tropical jellyfish are moving further and further south, and that climate change-induced warming of our oceans will likely increase this trend.

If you are in tropical Australia:

- Follow DRSABC, always.

- Remove the person from the water.

- Call 000 if they have more than a localised sting or look/feel unwell and seek help from a lifeguard if possible.

- Pour on lots of vinegar, for at least 30 seconds, to prevent further nematocyst discharges.

- Flick off any tentacles with a stick or your fingers.

- If there is no vinegar, flick off the tentacles and rinse with sea water (not fresh water, which may cause further nematocyst discharge).

- Prevent the person from rubbing the area.

- Apply a cold pack for pain relief (though heat may be just as good or better, who knows!).

- Reassure the person, try to keep them still, and stay with them until the ambulance arrives.

However, it is advised to treat a sting in a tropical area as for non-tropical areas if you are 100% certain it was a bluebottle, and the person is well with a single sting.

If you are in non-tropical Australia:

Douse the area in sea water (not fresh water), pick off remaining tentacles, and then immerse the area in hot water if available. Seek medical assistance immediately if they become unwell. Here, the priority is pain relief, as it is a non-fatal and self-limiting sting.

Despite what movies may suggest, do not urinate on jellyfish stings. As you don’t know your urine’s pH, you risk causing a massive discharge of the nematocysts and making things worse.

Enjoy your next swim!

Dr Brooke Ah Shay is a GP in the Northern Territory; formerly working in Arnhem Land, she is now completing her Masters of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in Darwin.