While use increases in under sixes, the TGA has issued another warning over counterfeit melatonin products available in Australia.

Melatonin has become a bedtime staple in many households with young children, yet a new systematic review suggests clinical practice has sprinted far ahead of the evidence, say the authors of a new JAMA paper.

Drawing on 19 studies published between 2000 and 2025, the systematic review found steep increases in prescribing, prolonged use, and accidental overdoses in children aged 0 to 6 years.

However, they found surprisingly little data on long-term safety or effectiveness, particularly in children with typical development.

The release of the paper last month coincided with an updated safety advisory from Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration about imported counterfeit melatonin products.

“Laboratory testing of several imported unregistered melatonin products has confirmed they are counterfeit under the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989,” the TGA statement said.

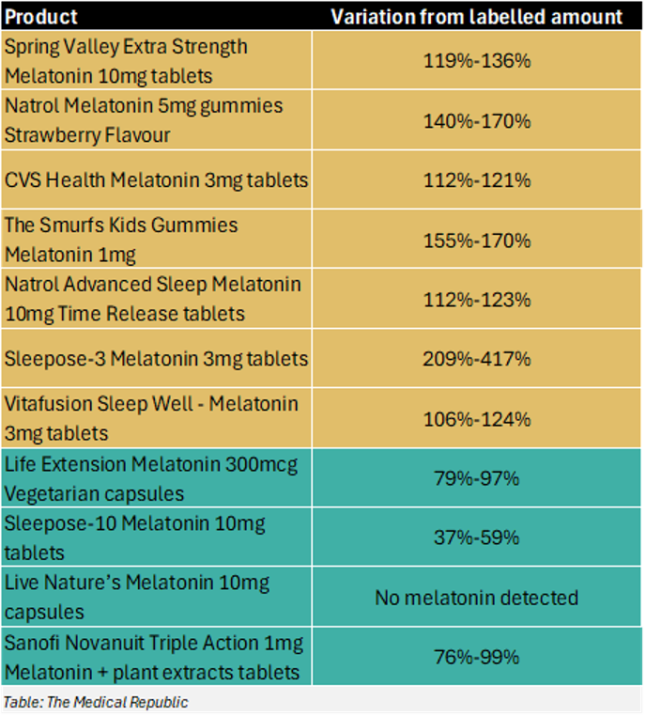

“The results indicate significant discrepancies in the actual melatonin content compared to the labelled amounts. One product contained more than 400% of the labelled content and another containing no melatonin at all.”

Authors of the JAMA paper used observational registry and poisoning data from Europe, Australia and the United States to paint a consistent picture – melatonin use in young children has surged over the past two decades, in some settings by as much as fivefold.

Extended use is common, with up to half of children continuing prescriptions two to three years after initiation, far beyond the duration studied in clinical trials.

At the same time, melatonin has emerged as the leading cause of unsupervised medication exposure and overdose in young children presenting to emergency departments, a trend that has accelerated in the past decade.

While most ingestions result in minor effects, serious outcomes, including rare deaths, have been reported, the authors wrote.

Against this backdrop of widespread and often prolonged use, the evidence base for benefit was narrow. Only five interventional trials examined efficacy in young children, enrolling just 167 participants in total, all with autism spectrum disorder or related neurodevelopmental conditions.

Across these trials, melatonin consistently shortened sleep onset latency, often by clinically meaningful margins, with relatively few short-term adverse events.

Effects on total sleep time and night awakenings were mixed, and benefits tended to diminish after discontinuation. No trials evaluated melatonin in children with typical development, and none systematically assessed outcomes beyond two years.

The review also underscores what was missing. Data on long-term health outcomes, including growth, pubertal development and broader behavioural effects, were sparse and largely qualitative.

“Two trials provided qualitative reports of long-term growth and development,” the researchers wrote.

“One, a four-week study that assessed precocious puberty after treatment, found no association with development.

“The other, a one-year study, reported small increases in body mass index and body mass index z scores, with no differences between treatment groups (i.e., melatonin vs control) but did not provide young child–specific results.”

Methodological quality was variable, with many studies limited by small sample sizes, short follow-up, and inadequate power. In practice, this leaves clinicians with little evidence to guide decisions about prolonged use that has become increasingly common.

For health professionals, the authors suggested the message was less about abandoning melatonin altogether and more about recalibrating its role.

The available evidence supported short-term use, under medical supervision, for young children with specific neurodevelopmental conditions after behavioural interventions had been tried.

They also said the evidence did not support routine or extended use in children with typical development.

The findings also highlighted the need for more consistent counselling around sleep hygiene, screen time and behavioural strategies, which remained first-line and effective for most young children.

“These findings support clinical practice of recommending melatonin for young children with ASD after behavioural intervention and medical supervision, but there was no evidence to support this practice in children with typical development,” the researchers wrote.

“The immediate next steps are threefold. First, we must improve paediatrician and parent support of behavioural sleep practices, such as reducing night-time screen time.

“Parent education is critically needed as parents may interpret over-the-counter availability as an indication of safety and use melatonin in substitution of behavioural sleep practices [e.g., complete or gradual extinction practices, structured bedtime routines, reduction of screen time before bed].

“Second, paediatricians should assess child and parent supplement usage, as convenience samples of US parents have noted that not all parents may discuss their melatonin usage with their health care professionals but still use melatonin for extended periods.

“Third, even in children with ASD, long-term medical follow-up is required given the sustained use beyond three years.

“Long-term solutions are twofold. First, based on overdose increases in non-regulated countries, allocating melatonin to a prescription medication may improve use estimates, medical supervision and accurate formulation.

“Second, development of discontinuation resources to safely reduce melatonin use, while promoting healthy sleep practices, is needed to meet recommendations for children with typical development.”

To make matters worse, Australia’s medicines watchdog has issued a second warning in six months over dodgy melatonin products.

Last month the TGA issued an updated safety advisory about a range of unregistered and counterfeit melatonin products that had been imported into the country and identified to be fakes after laboratory testing.

“The results indicate significant discrepancies in the actual melatonin content compared to the labelled amounts. One product contained more than 400% of the labelled content and another containing no melatonin at all,” the safety advisory read.

“This variability in melatonin content raises serious safety concerns for consumers, including the risk of accidental overdose and hospitalisation, especially in children.”

The TGA identified seven products that contained significantly more melatonin than the labelled amount, while a further four products contained significantly less.

There have been two changes from the TGA’s original warning that was released last September: Nutraceutical Sleepose-3 Melatonin 3mg has been removed from the “too much melatonin” list, while Sanofi Novanuit Triple Action 1mg Melatonin + plant extracts tablets have been added to the “not enough melatonin” list.

The TGA advised consumers to be look for an AUST R or AUST L number on product packaging to determine whether the product is on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods. Being on the ARTG means a product has met a variety of Australian standards, including that the ingredients listed in the product are accurate, and that the product was made under strict safety and quality standards.

A prescription is required to purchase melatonin in Australia, save for a handful of specific circumstances in adults. Serious side effects – including accidental overdose and hospitalisation – can occur when melatonin is taken without appropriate medical oversight.

The TGA has also advised consumers to:

- Stop taking the unregistered products immediately, and to take any remaining items to a pharmacy to be disposed of safely.

- Report any side effects that have occurred after taking these medications, or any other similar medications.

- Seek advice from your treating medical practitioner if you have any concerns relating to these (or other similar) products.

Read the TGA’s full summary report on the counterfeit melatonin products here.