With dementia diagnoses on the rise, multi-component lifestyle interventions are needed to reduce the risk of cognitive decline, writes Dr Malvindar Singh-Bains

Dementia, a term broadly used to describe a range of symptoms, including memory loss, impaired intellect, rationality, social skills and physical functioning, affects almost 50 million people worldwide. That number is predicted to increase to 131.5 million people by 2050.1

As of 2018, approximately 436,366 Australians live with dementia and these numbers are expected to increase to more than one million individuals by 2058.2 Dementia has become the second leading cause of death in Australia3 and the single greatest cause of disability for Australians over the age of 65.4

In terms of financial impact, dementia is estimated to cost Australia more than $15 billion in 2018, and with the current statistics, these costs are projected to be more than $36.8 billion in the absence of a medical breakthrough by 2056.5

In more recent times, it has been widely acknowledged that some individuals experience a degree of memory loss greater than that traditionally experienced with ageing, without any other overt signs of dementia.

This has been termed Mild Cognitive Impairment or MCI.

It is currently estimated that individuals diagnosed with MCI have a three to five times increased risk of developing dementia than others of the same age.6 Therefore, delaying the progression of MCI to the development of conditions characterised by significant dementia, such as Alzheimer’s disease, would significantly reduce the prevalence of dementia in Australia and worldwide.

So how can clinicians aid the global effort to prevent cognitive decline and foster an environment for better brain health for patients? Here, we investigate some methods and evaluate their efficacy and the evidence behind them.

A MEDITERRANEAN DIET

A systematic review of 664 studies were screened to determine whether there was an association between the Mediterranean diet and cognitive impairment.7

The Mediterranean diet involves a high intake of vegetables, legumes, fruits, cereals, and unsaturated fatty acids (mostly in the form of olive oil), moderate to high intake of fish, low to moderate intake of dairy products, low intake of meat, and saturated fatty acids, and a regular, but moderate, intake of alcohol.

Based on the systemic review results, greater adherence to the diet was associated with a reduced risk of both MCI and Alzheimer’s disease. Individuals with a high adherence to the diet had a 33% reduced risk of cognitive impairment compared with those with a low adherence.

Among cognitively normal individuals, higher adherence to the diet was associated with a reduced risk of developing MCI and Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, adherence to the Mediterranean diet predicted a lower conversion of amnestic MCI to Alzheimer’s disease.8

Taken together, pushing the motto “What’s good for the heart, is good for the brain” is a beneficial strategy for clinicians to advocate for the Mediterranean diet for patients at risk of dementia.

COGNITIVE TRAINING

Cognitive training involves performing tasks targeting aspects of cognitive function including memory, attention and language.

This training includes repeated problems and exercises that are designed to work out and drill impaired cognitive abilities under various conditions. This approach is most often used for improving cognitive functions such as speed of processing, useful field of view [the visual area over which information can be extracted at a brief glance without eye or head movement] and attention.

Cognitive training also involves teaching strategies that exploit spared cognitive reserves to improve impaired ones. For example, some memory-training techniques rely on visual imagery to support episodic memory.

Other techniques involve applying strategies that optimise cognition, such as spaced retrieval or self-cuing memory optimisation methods.

Cognitive training can also result in improving meta-cognition (i.e. the knowledge that participants have about memory mechanisms and their own memory), and cognitive self-efficacy (i.e. the idea that participants can practice some control over their cognition).

A Cochrane review of all randomised controlled trials of mental engagement/cognitive training interventions between 1970 and 2007 evaluated the effectiveness of cognitive training programs to improve memory in normal and MCI adults aged 60 years and older.9

The results of the review suggests that for both healthy adults and individuals with MCI, immediate and delayed verbal recall improved significantly through cognitive training treatment compared with no treatment.

Other systematic reviews of randomised control studies and observational studies have obtained similar results.10, 11

However, based on these large reviews, it is unclear if the improvement is attributed specifically to the cognitive intervention. One major limitation of these studies is the need for researchers to use larger samples of participants and randomised controlled designs. The population of individuals living with MCI is heterogeneous and not everyone with MCI will progress to dementia.

This heterogeneity increases the importance of relying on relatively large sample size studies.

Furthermore, the identification of proper outcome measures for these studies is crucial. Most nonpharmacological studies of MCI have used cognitive symptoms as their endpoint. Yet, conversion to dementia may be viewed as a more appropriate outcome.

Considering that MCI and dementia are now seen as a continuous spectrum, there may be an advantage in using symptom progression as a useful outcome.

However, the manner in which progression is quantified and defined needs to be determined. Thus, a consensus among all the researchers working on cognitive training for individuals with MCI needs to be reached to provide standardised guidelines for the improvement of cognitive training as a treatment option.

A MULTIFACTORIAL APPROACH TO DEMENTIA

Data obtained from retrospective studies have reported declining dementia prevalence rates in certain populations since the 1970s.

Some of these studies have sug gested that higher levels of educational attainment in these specific cohorts supports the accumulating evidence that formal education is beneficial for reducing the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.12, 13

Some studies have also noted that the declining dementia incidence and prevalence in these cohorts also had substantial improvements in managing cardiovascular risk factors (diabetes, obesity, smoking, and hypertension) as well as declines in smoking, heart disease and stroke.

Therefore, given that most cardiovascular risk factors are connected to a general notion of a healthy lifestyle, focusing on a single lifestyle factor (i.e. simply adjusting diet or enforcing cognitive training approaches alone) may be insufficient to reduce an individual’s risk of developing dementia. More recent studies suggest a more effective strategy to tackle dementia is to address multiple risk factors simultaneously.14, 15

The idea of a multifactorial approach to reduce the risk of cognitive decline was tested in the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER).

The FINGER study was the first published randomised controlled trial on multivariate risk factors and cognitive decline. (16)

The results from this study suggest that individuals with higher cardiovascular risk profiles experience significant improvements in overall cognitive performance and executive functions with a multi-component lifestyle intervention including: physical activity, nutritional guidance, cognitive training, social activities, and management of cardiovascular risk factors.

Taken together, clinicians can advocate for multi-component lifestyle interventions to reduce the risk of cognitive decline for elderly patients.

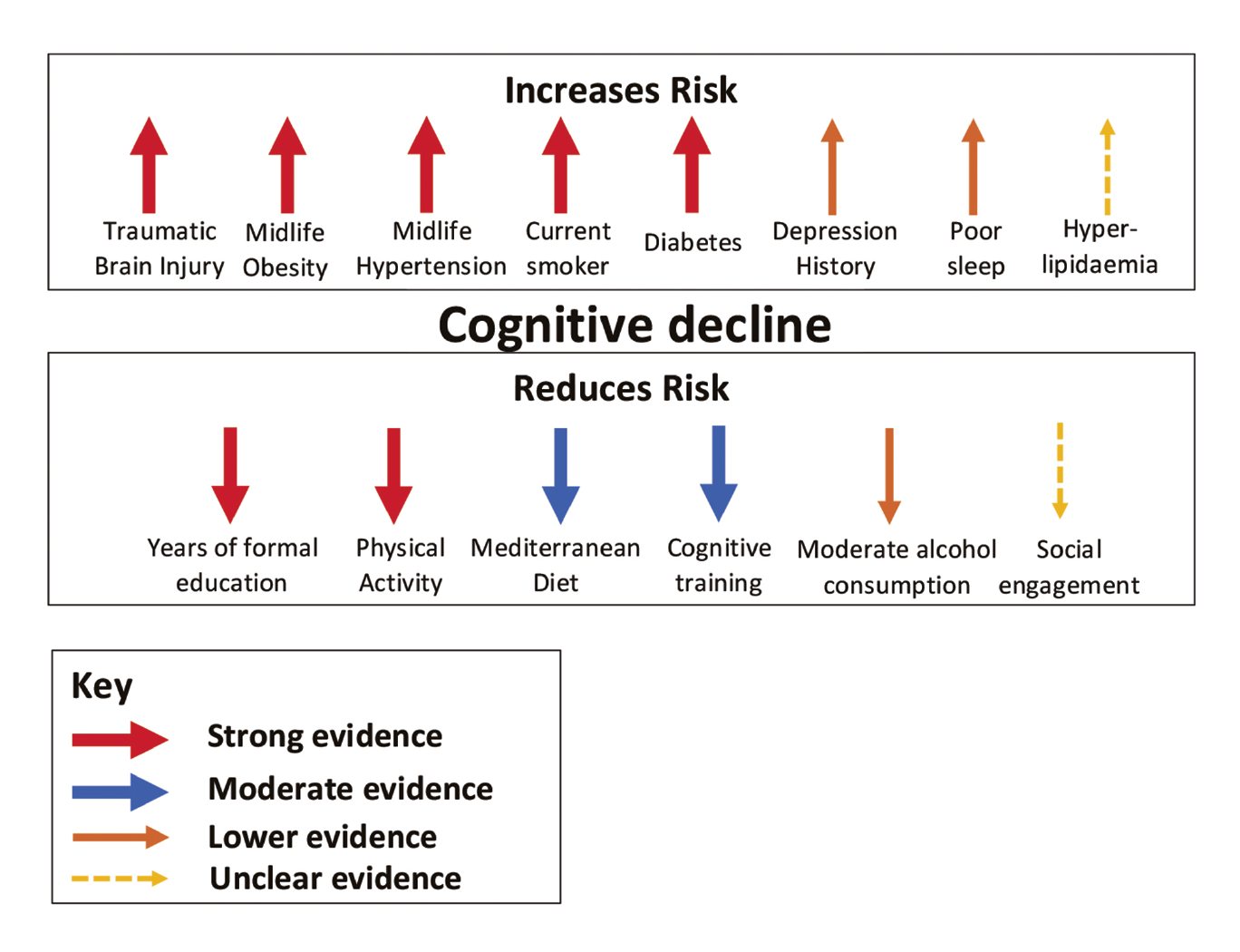

The diagram on this page (above) summarises the current risk factors thought to have the most significant impact on the rate of cognitive decline.

It must be noted that cognitive training and enforcement of the Mediterranean diet have “moderate” levels of evidence to suggest a reduction in cognitive decline.

Therefore, combining these methods with physical activity and management of risk factors thought to increase the risk of cognitive decline (especially cardiovascular factors) encourages a more cumulative approach to tackling MCI and progression to dementia.

The following resources are helpful for general practitioners when discussing brain health related activities for patients with mild cognitive impairment and dementia:

• Your Brain Matters https://yourbrainmatters.org.au/ Your Brain Matters is Dementia Australia’s dementia risk reduction program.

• Brainy App https://brainyapp.com.au/

BrainyApp was developed by Dementia Australia and Bupa Health Foundation to raise awareness of the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia

• Dementia Australia //www.dementia.org.au/

Dr Malvindar Singh-Bains, PhD, is a Freemasons Research Fellow at the Centre for Brain Research at the University of Auckland and co-chair of Huntington’s Disease Youth Organisation NZ

References:

(1) Alzheimer’s Disease International https://www.alz.co.uk/about-dementia

(2) Dementia Australia (2018). Dementia Prevalence Data 2018-2058, commissioned research undertaken by NATSEM, University of Canberra

(3) Australian Bureau of Statistics (2017) Causes of Death, Australia, 2016 (cat. no. 3303.0)

(4) Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2012) Dementia in Australia

(5) The National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling NATSEM (2016) Economic Cost of Dementia in Australia 2016-2056

(6) Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, Tangalos EG, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia—mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:1133–1142.

(7) Singh B, Parsaik AK, Mielke MM, Erwin PJ, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Roberts RO. Association of mediterranean diet with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease. 2014 Jan 1;39(2):271-82.

(8) Scarmeas N, Stern Y, Mayeux R, et al.: Mediterranean diet and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol2009; 66:216–225Medline, Google Scholar

(9) M. Martin, L. Clare, A.M. Altgassen, M.H. Cameron, F. ZehnderCognition-based interventions for healthy older people and people with mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1) (2011), p. CD006220

(10) C. Stern, Z. MunnCognitive leisure activities and their role in preventing dementia: A systematic reviewInt J Evid Based Healthc, 8 (2010), pp. 2-17

(11) M. Valenzuela, P. Sachdev Can cognitive exercise prevent the onset of dementia? Systematic review of randomized clinical trials with longitudinal follow-up

Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 17 (2009), pp. 179-187

(12) C.L. Satizabal, A. Beiser, G. Chene, V.A. Chouraki, J.J. Himali, S.R.Preis, et al.Temporal trends in dementia incidence in the Framingham Study

Alzheimers Dement, 10 (4 Supplement) (2014), p. P296

(13) E.M. Schrijvers, B.F. Verhaaren, P.J. Koudstaal, A. Hofman, M.A.Ikram, M.M. Breteler Is dementia incidence declining?: Trends in dementia incidence since 1990 in the Rotterdam Study

Neurology, 78 (2012), pp. 1456-1463

(14) F. Mangialasche, M. Kivipelto, A. Solomon, L. Fratiglioni Dementia prevention: current epidemiological evidence and future perspective

Alzheimers Res Ther, 4 (2012), p. 6

(15) J.J. Monsuez, A. Gesquiere-Dando, S. Rivera Cardiovascular prevention of cognitive decline

Cardiol Res Pract, 2011 (2011), p. 250970

(16) T. Ngandu, J. Lehtisalo, A. Solomon, E.Levalahti, R.A. Ahtiluoto, L. Backman, et al. A 2-year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial Lancet (2015), 10.1016/S0140–6736(15)60461-5