New Australian data could revolutionise how mental health patients are monitored in the long term.

Monthly blood tests to monitor schizophrenia patients taking clozapine could soon be a thing of the past.

While clozapine is the most effective option for patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, some clinicians are reluctant prescribe it due to potentially life-threatening neutropenia requiring regular blood tests for as long as patients continue treatment.

But new research, published in The Lancet Psychiatry, suggests patients who complete two years of regular blood tests without a serious neutropenic event may not require ongoing monitoring.

“After being monitored on clozapine for two years, the risk of experiencing dangerously low neutrophils is so low that people don’t need to be doing blood tests every single month for the rest of their lives – especially if they have tried clozapine before,” said senior author Professor Dan Siskind, a psychiatrist from Brisbane’s Princess Alexandra Hospital.

Researchers reviewed over two million blood tests from 26,000 Australians and New Zealanders taking clozapine to explore associations between its usage and the risk of neutropenia.

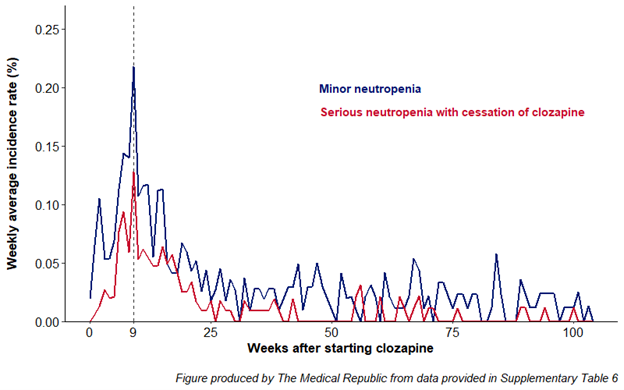

One in 25 of patients developed minor neutropenia (neutrophil count of 1.0-1.5 x 109/L) over a median follow-up of almost four years, while 2% had a serious neutropenic event (neutrophil count less than 1.0 x 109/L). Half of the patients who had a serious neutropenic event stopped taking clozapine as a result.

The weekly average incidence rates of serious neutropenia leading to clozapine cessation (0.13%) and minor neutropenia (0.22%) both peaked nine weeks after nine weeks of treatment before falling for the remainder of the monitoring period.

No neutropenia-related deaths were identified.

How clozapine interferes with neutrophil production isn’t exactly clear, but the researchers have a few ideas.

“Evidence suggests an immune-based cause is responsible for selective destruction of neutrophils, which is also implied by the observation of recurrent severe clozapine-associated neutropenia occurring rapidly after [a] clozapine challenge, suggesting an amnestic response,” they wrote.

Australian guidelines recommend schizophrenia patients have weekly blood tests for the first 18 weeks of clozapine treatment, then shift to monthly blood tests for as long as they continue the treatment.

Clinicians are required to review and record recent blood tests results using a patient monitoring system (e.g., Pfizer’s Clopine Central) before prescribing clozapine. Professor Siskind hopes the findings will “provide the basis for a change in practice, making clozapine more accessible to those who need it and improving the lives of people on the drug”.

Conjoint Professor Jackie Curtis, a psychiatrist and executive director of the MindGardens Neuroscience Network, agreed the “robust” findings could have a major impact on clinical practice, including increasing the number of people who may be able to benefit from clozapine, but said the implications of any potential changes to monitoring guidelines would need to be carefully considered.

“Yes, [the monitoring program] is for neutropenia. However, there are other blood tests that are essential to the physical health of someone with schizophrenia – the metabolic monitoring for heart disease and diabetes. If we take away the monthly blood tests, there’s a risk that we’re not going to be looking at these other factors. That is important because cardiometabolic issues are the main reason for poor health and premature death in this group,” Professor Curtis told The Medical Republic.

“When [patients] come into the clozapine clinic on a regular basis to get their blood tests, your GP or psychiatrist can ask about other important factors such as diet, smoking or exercise incidentally, which might get missed [if the guidelines were to change.

“That’s not a reason to go ahead [with any potential changes], but we need to be mindful about what sort of actions could replace the monthly tests.”