If our next National Health Reform Agreement doesn’t do what it was introduced to do 14 years ago and incentivise a proper integration between general practice and hospitals, it’s going to be groundhog day for the foreseeable future for general practice.

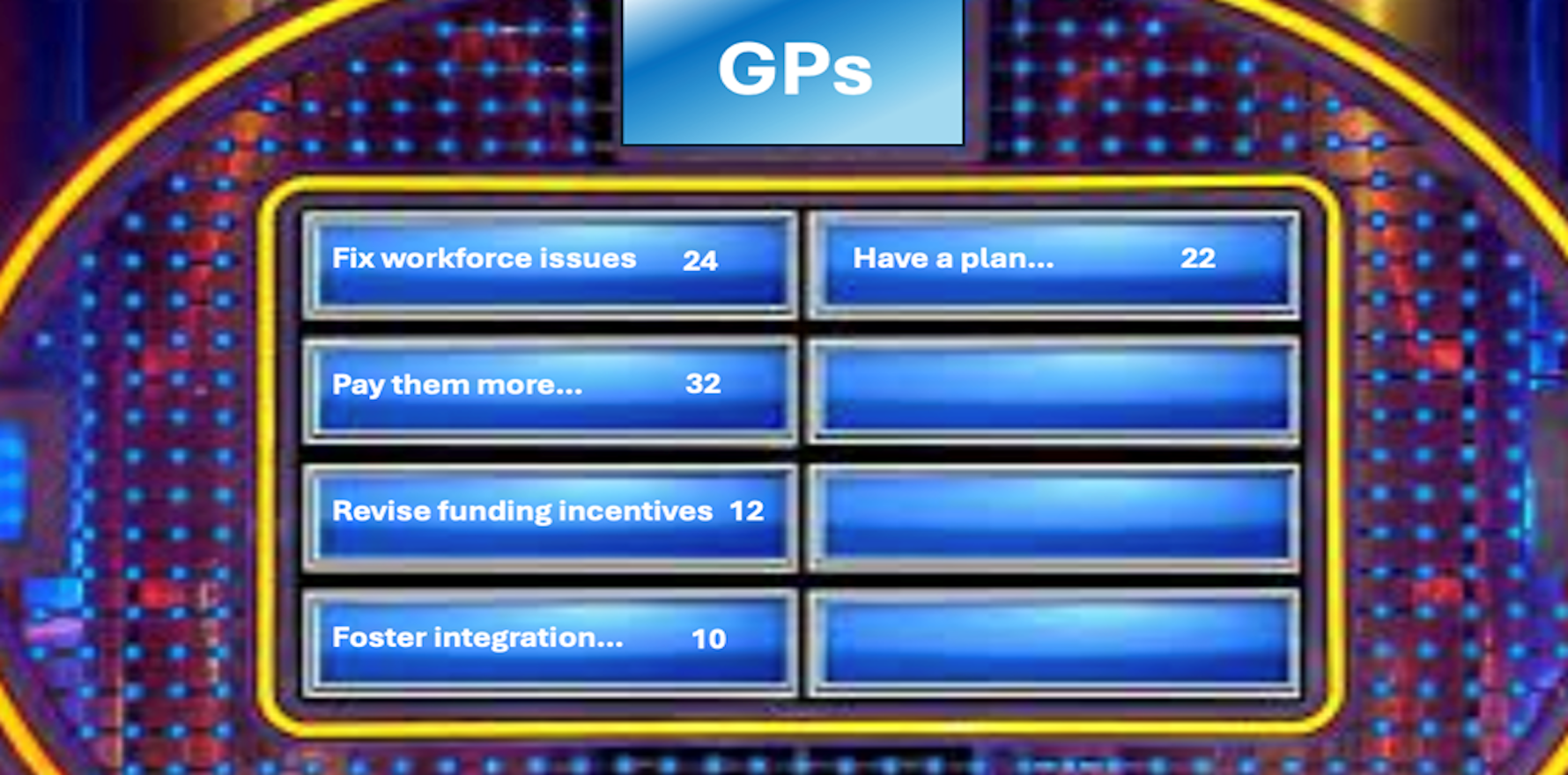

We surveyed 100 GPs and asked them to nominate the top five things that might most transform the profession to be the true epicentre of our healthcare system in the not too distant future, one where they are allowed to focus on effective chronic care management out in the community

This is what they said, not in order of priority.

- Fix workforce issues – train more, distribute them better regionally, optimise scope of practice to assist GPs, not compete with them and improve the IMG process.

- Pay them better – pay them more for bulk billing (a lot more than the latest $9 billion), longer consults, after hours and remote work, fix gender pay bias

- Revise funding incentives: 40/60 block funding to fee for service, with block funding incentivising outcomes/value (somehow)

- Foster integration and care co-ordination – with providers around them including specialists, allied health and hospitals

- Have a plan – Develop do a holistic 10 year national healthcare plan and vision integrating all points of the healthcare compass (Aged Care, Hospitals, NDIS, Specialists, Allied, even social determinants of health, the whole shebang) and explain to GPs where they fit in.

Now you put them in the order you think they should go in terms of what GPs said and see if you can win GP Family Feud.

In fact, the above list wasn’t actually a survey, apologies.

We got it by asking Google AI to tell us its top five priorities for reforming general practice and to put them in order of priority. That’s the list in priority order above.

Before anyone asks, of course Google AI did not come up “with fix the gender bias in GP remuneration” even though Professor Louise Stone is all over the internet explaining why it occurs and how we can fix it. AI still sometimes needs a little help because, as a creature of the internet, it is a natural misogynist.

One other thing about this list. Is anyone worried that even AI thinks we need to have an overall plan for healthcare and provide GPs proper context within that plan so they have a roadmap of sorts?

I’m not a GP, but although that’s not a bad list, although I’m not sure AI got the order or detail right at all.

Something that would almost certainly lead to transform the GP sector isn’t really on the list at all … although you could say it’s part of point No 4.

It’s our next National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA).

Im hoping most GPs will know about it, I’m not sure many would recognise it’s potential significance to their futures.

This is what the government says the main goal our NHRA is on the current Department of Health Disability and Ageing website:

“The NHRA is an agreement between the Australian government and all state and territory governments.

“It commits to improving health outcomes for Australians, by providing better coordinated and joined up care in the community, and ensuring the future sustainability of Australia’s health system.” [our emphasis]

So far, the NHRA, which has been going a full 14 years now, and has had two iterations already, has achieved none of this.

Hospitals are hospitals, GPs are GPs and mostly, never the twain shall meet.

At their structural core, Australian hospitals still largely function with a narrow focus on episodic and acute episodes of care.

Once a patient is admitted, they’re managed within a hospital’s own, often bespoke, and mostly siloed, network of care teams, EMRs, IT and admin systems.

The only significant development in connectivity thinking so far from the states, who manage our public hospital networks, is for public hospitals within a state to talk to each other better via projects like NSW’s single digital patient record, or Victoria’s statewide hospital HIE (notably, neither are working that well so far).

No serious focus or effort has been made by any of the states so far to get their hospital networks to talk meaningfully to community-based care networks.

Yet every key policy document and healthcare review (state and federal) of the last decade points to only one way forward if we are to address our impending chronic care crisis which is threatening system collapse: the rapid integration of the tertiary and primary care sectors – data and patient fluidity between the two sectors.

When patients discharge to home from a hospital, transfer to aged care, or need ongoing GP follow-up, the transition is hit and miss, uncoordinated, and often hazardous.

A big problem with all this existing system legacy, complexity and duplication is that it is amplifying our existing and increasingly dire workforce problems.

Clinicians across both the hospital and community settings are currently charged with plugging all our continuity of care and integration gaps manually.

This means more admin and less time with patients. It’s hugely inefficient but worse, all this additional admin and paperwork is a significant contributor to provider burnout both in hospitals and in primary care.

If the NHRA actually did what it is supposed to do, it would set us properly on a path to system and GP role transformation.

The federal government has embarked on a significant program over the last few years to lay the foundations for a new national digital health infrastructure designed to facilitate far better technical interoperability between hospitals and community care.

This is the “sharing by default” program, lots of plans of which are in play already.

The ability to achieve technical interoperability is, of course, an important foundational element of integrating the two sectors, but in the end the integration of hospitals seamlessly to community-care networks is not just a technology problem.

It’s a cultural, political and funding problem with its problematic roots in our federated model of system management: states run hospitals, the commonwealth runs most community-care networks and until now, little actual effort has been given to the integration of the two.

The third NHRAagreement is due before the middle of next year. It was due this year but thankfully (we think) was delayed.

But GPs and system advocates for transformational change may have a big problem if they like the idea of an NHRA that actually stimulates sensible system change.

There is a lot of secrecy and opaque process surrounding how the current NHRA is unfolding.

It is obviously a highly sensitive negotiation from a political perspective. But it seems to have become Secret Policy People Business. High-level political and policy people’s eyes only.

Surely that’s a dangerous way to run a process on which the future transformation of healthcare system and the GP sector depends.

As mentioned above, the federal government through DoHDA has and is doing a lot of work to build out much better national infrastructure for digital interoperability and connected care across Australia – think Health Connect Australia, 1800 Medicare, a properly connected and atomised My Health Record, telehealth integration, and plans for a national HIE that won’t just connect hospital networks to each other.

But all this work has as a fundamental flaw if we really want to connect hospitals into our integrated care vision – hospitals all use legacy IT systems that don’t communicate with primary-care software, aged-care platforms, or standard digital health tools and standards.

While the states are talking “cooperation” in the key interoperability program of Sparked (a CSIRO-run initiative to equalise clinical coding as a preparation for software development standardisation), they can still choose to do what they want to do when they want to do it in terms of key levers like funding and technical integration.

The big problem with the states is that politics runs far deeper into their management of health than it ever has at the federal level.

Hospitals are key chess pieces in state elections. Outside of elections everything that goes wrong in hospitals reverberates far harder for the politicians because hospitals and their mistakes are so big and visible in a state context.

Over time the technological isolation of hospitals has begun to mirror their organisational isolation from the rest of the system in a manner that has become so systemic the status quo has become very hard to perturb.

A properly constructed NHRA offers us the chance to start changing this dynamic: to incentivise state governments and the hospitals to start meaningfully participating in the interoperability momentum that is being stimulated at the federal level.

From a patient perspective, today they have very little information or reasonable navigation resources to empower them to improve their healthcare journeys . If we could provide it to them, the system will likely gain an additional level of efficiency, as patients will do much of the work healthcare providers are having to do now.

In addition to new funding signals and better data-sharing infrastructure, a good NHRA would encourage meaningful joint governance between hospitals and the community sector, particularly with GPs.

Clinical integration of the sort required to connect hospitals properly to the community requires a proper power balance in the executive and system-level leadership of both the state-run hospitals (eg, LHDs, HHSs) and the federally run community-care provider organisations (eg, PHNs, the colleges etc).

Work on this sort of joint governance arrangement has been ad hoc to date. It has been promoted by various champions of “joint commissioning” but if you look around the states today, a lot of that enthusiasm has evaporated post-covid and amid the rapidly growing day-to-day logistical and budget issues of simply keeping a busy hospital running.

Without embedding such governance within a federal and state agreement such as the NHRA, and somehow incentivising it properly with funding, something like this is not likely to ever be a serious initiative.

Our next NHRA must be brave and bold

Today, hospitals are measured and paid in large part based on inpatient metrics – length of stay, bed occupancy, throughput and in-patient procedure efficiency and cost. These existing models include virtually no signals for post-discharge continuity of care within the community.

For those in state policy positions, and everyone around them, including our GP leadership, who have influence in the next NHRA negotiation, take note.

If we end up with yet another financial deal between the feds and the states on hospitals, we can kiss all the good work everyone is doing around interoperability, and connected care, goodbye for the foreseeable future.

And with that we can kiss one of our biggest levers for positive change for the GP sector goodbye as well.

The NHRA needs to be an ambitious and bold new strategy play that synchronises all the infrastructure work going on, and incentivises the states and the hospital sector to seriously start concentrating on integrating their bricks-and-mortar vote-winning palaces of acute care into local community care provision hubs.

The following are some of the basics that need to change in our next NHRA – this of course may be a naïve list that others need to add to or edit, but it’s enough hopefully to give everyone who is thinking this through some starting points.

Mandate continuity-based KPIs for hospitals and primary care

Rather than bed turnover and procedure volumes only, hospital performance frameworks should be balanced to include measures for post-discharge follow-up and continuity, including seamlessly starting to work with GPs, specialists and allied care in the community, and for hospitals themselves to be able to better manage a lot of their patients directly in the community via new virtual care programs and better connectivity with GPs.

Tie funding to care transitions

The NHRA should pave the way for developing shared budgets to specifically incentivise hospital-community transitions. A significant element of this should be addressing joint commissioning models, bundled payments, or discharge-to-care agreements. Some of the money needs to go to incentivising at the GP end.

Create conditions for proper collaborative governance between the sectors

Money should be set aside to incentivise and build joint leadership structures by region (defined probably by PHNs and their local overlapping hospital networks) where hospitals, primary care groups, PHNs, aged care facilities, patient groups and mental health community providers jointly use locally acquired population research and then design and build out local digital continuity between all the stakeholders.

This would mean adjusting how care continuity and care pathway innovation is delivered and funded by regional (patient) needs.

Such groups might ideally start managing a single regional heatlhcare budget which incorporates all the funding of all the elements of the stakeholders at the table. This idea is probably too far for an NHRA now, but the states and the commonwealth should pick some advanced regions and maybe pilot the idea.

Incentivise and organise for better patient data, analytics and engagement strategies

The next agreement should imbed the collection and analysis of regional patient data to help local health management develop specific regional strategies for deployment of connected care services.

This probably means that DoHDA will need to get a little more serious about how they manage PHNs, who theoretically have always been charged with this task, but have essentially just been used by the department to deploy tactical inititiatives top down. It would be interesting to see what the Boston Consulting Review into PHNs has to say about this problem. That is if DOHDA releases that report publicly – so far they are sitting on it.

The AIHW should probably be built into this model as it’s doing a pretty good job already with data and analytics.

Everyone should imagine that AI might significantly enhance this initiative.

Using this data, the joint provider leadership teams should then be measured and incentivised to build out digital solutions that promote better localised patient experience, promote increasing patient engagement and participation in the provision of their local community-based care and facilitate hospital to community patient transition (both ways).

A key objective of the connected-care revolution that is unfolding around us (and around the world) is reimagining the patient experience as a continuous, seamless, person-centred journey from community to hospital and back – sometimes never to the hospital ideally.

Today hospitals in Australia remain mostly bricks-and-mortar and digital health islands lost to a series of disconnected community care provider services, GPs being one of the most important among them.

The commonwealth’s interoperability work is laying the rails for being able to make information flow seamlessly between providers and providers and patients in both sectors soon.

But without institutional, policy and funding reform – something that a well-constructed NHRA can start us down the track on – our much hoped-for healthcare system transformation will almost certainly continue to stall and with it GP sector transformation as well.

True connected care will come when hospitals anchor themselves within integrated systems—shifting focus from their four walls to the lived experience of each patient out in the community, very often, as managed by general practice.

Note: If you’re interested in canvassing some of the latest models of connected care being used in hospitals, including case studies, and the sort of funding alignment changes and political will that might be needed to expedite hospital connectivity and transformation, then maybe have a look at our upcoming summit: New Models of Care Reshaping the Future of Hospitals, October 16, Aerial Centre, UTS, Sydney, HERE. Use this code – FUTURE20 – for a one off 20% off Tickets. If you have any queries on the summit, content or sponsorship you can contact greta@healthservicesdaily.com.au