A new study has made 'definitive' findings around pregnancy and the onset of multiple sclerosis.

Women who have been pregnant will experience the onset of multiple sclerosis more than three years later on average than those who haven’t, an international research team has found.

Datasets for 2557 women with clinically isolated syndrome (the precursor to MS) were compared to reveal that on average, patients who had been pregnant were diagnosed with their first multiple sclerosis symptoms 3.3 years later than women who hadn’t.

Similar delays were discovered among women who gave birth.

“While we might have had hints that we knew something’s going on between pregnancy and MS, this study is a definitive answer,” Dr Julia Morahan, MS Research Australia’s head of research, who was not involved in the study, told The Medical Republic.

“It’s showing that now, without a shadow of a doubt.”

Multiple sclerosis affects 25,600 Australians, and three out of four patients are women.

The condition is typically diagnosed in people in their 20s and 30s but can occur at any age, with 32 years being the global average age of diagnosis.

The data used in the Monash University-led study was taken from the MSBase Registry, which has been coordinating and gathering data for over 71,000 patients attending 160 clinics in 35 countries since 2001.

Dr Morahan said the incidence of multiple sclerosis was increasing, particularly in women, and that keeping patients within the clinically isolated syndrome stage for longer would be beneficial.

“So, this paper is really exciting from my perspective, because it is something that might be able to help us think about what factors are affecting the women living with multiple sclerosis,” she added.

“What this data shows on its own is that pregnancy is safe for women that have multiple sclerosis, and even that is a bit of a deviation from where we were a number of years ago, where people who had MS or had a diagnosis of MS really weren’t entirely sure whether they were able to be able to have children.

“All of the medical community now has shifted to understand that pregnancy is often positive for women with MS, and that there’s no reason not to go down that path if that’s something that they want.”

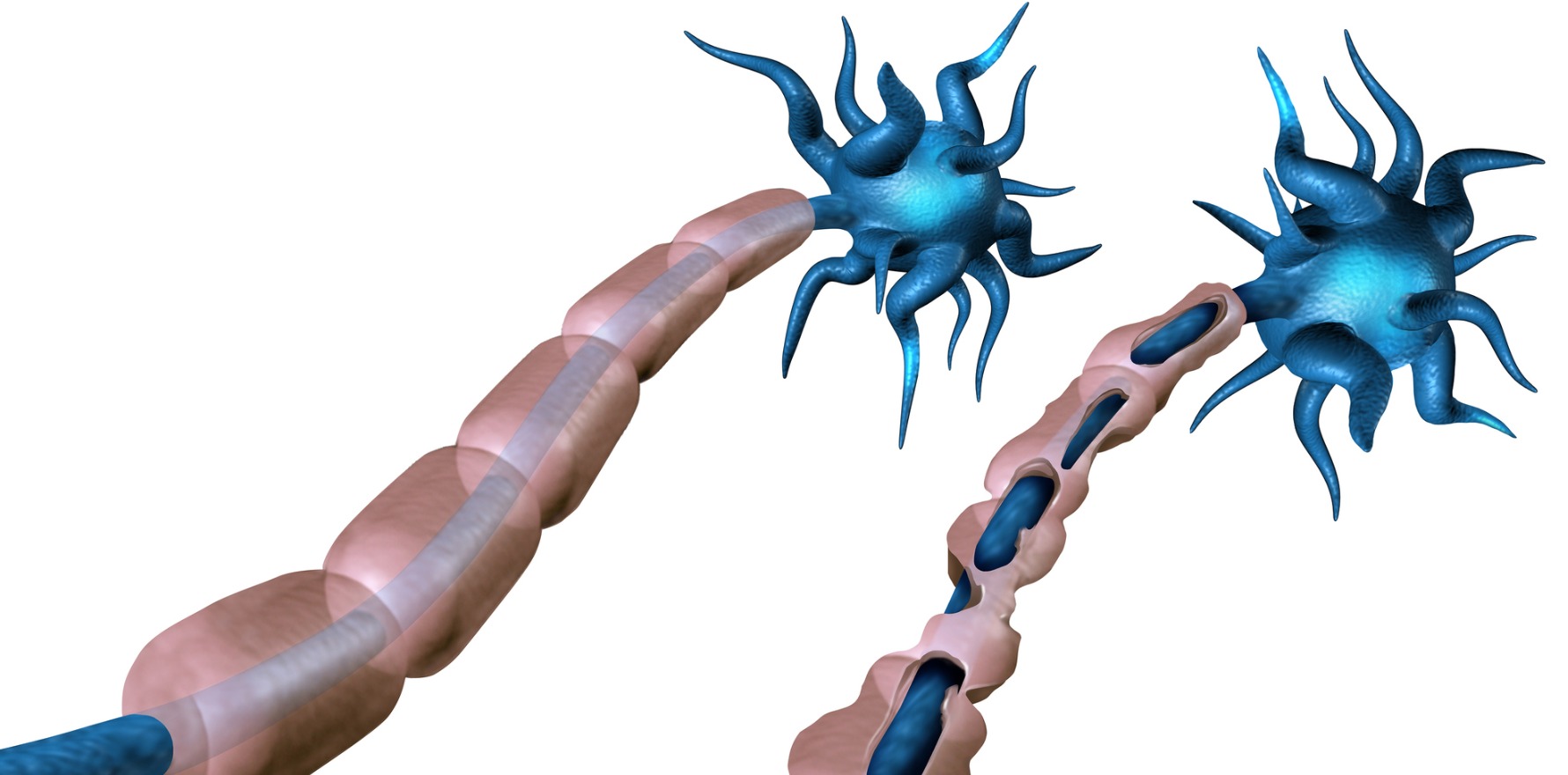

Immune system changes that occur during pregnancy mean women with multiple sclerosis fare better, but often have a rebound of the disease once they’ve given birth.

The next step in research will be determining what is behind the findings.

Dr Vilija Jokubaitis from the Monash University Department of Neuroscience, who led the study, said it could be that pregnancy suppressed the abnormal overactivity of the immune system that causes the condition, potentially long-term.

“At present, we don’t know exactly how pregnancy slows the development of MS, but we believe that it has to do with alterations made to a woman’s DNA,” Dr Jokubaitis said.