Slower recovery from low back pain is a marker for developing long-term disability and pain.

Early targeting of patients who are recovering slowly from low back pain could help prevent persistent back pain and associated disability, Australian researchers suggest.

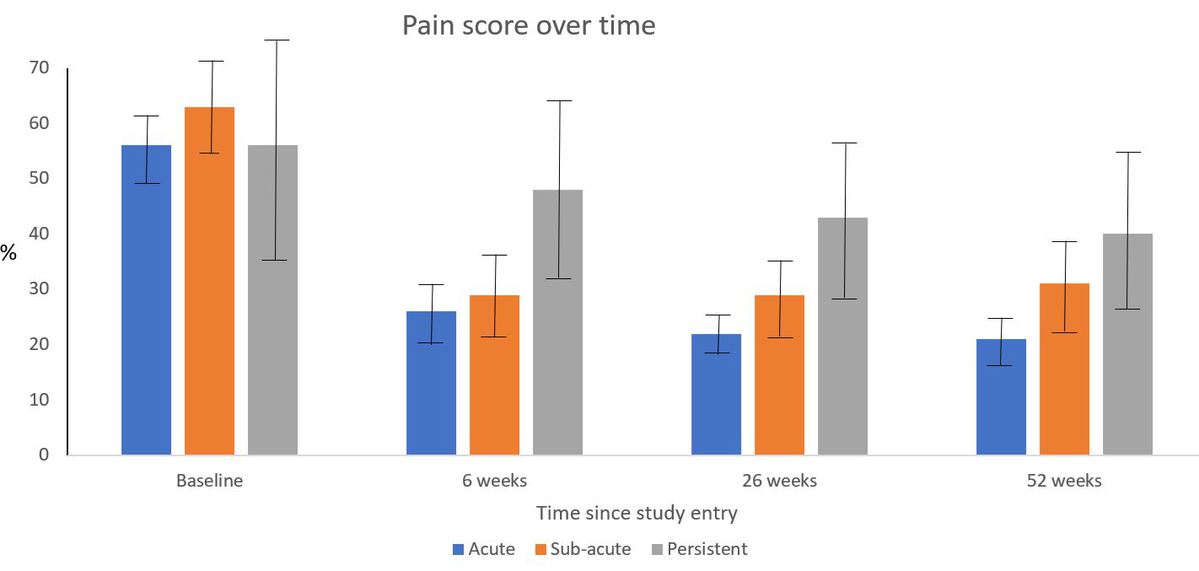

The team reported that people with acute and subacute non-specific low back pain (less than six weeks and six-12 weeks respectively) at study entry experienced substantial improvements in pain and disability in the first six weeks.

Conversely, people with persistent pain (12-52 weeks) at study entry had minimal improvements over time.

The authors noted that while most people with acute and subacute pain see early improvements, with those in the acute group experiencing greater reductions in pain and disability than those in the subacute group, many continue to experience ongoing pain and disability.

Identifying and escalating care in people with subacute low back pain who are recovering slowly could help reduce the likelihood of transition to persistent low back pain, they wrote in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

“This care might involve clinicians starting to look at other non-tissue-based contributors to their pain, such as any patient-specific psychosocial factors,” first author Dr Sarah Wallwork PhD told The Medical Republic.

“Escalation of care may also involve increasing patient understanding of ‘how pain works’, including how to reduce pain system sensitivity, while focusing on increasing function and participation in meaningful activities,” said Dr Wallwork, a physiotherapist and research fellow at the University of South Australia.

In addition to escalation of care, providing positive but realistic advice about the likelihood of symptom recurrence and reassurance that ongoing symptoms don’t necessarily represent serious pathology may also be beneficial, the authors noted.

Apart from time since pain onset, the researchers didn’t look at any specific prognostic indicators for prolonged back pain, Dr Wallwork told TMR.

“Having said this, we did conduct a couple of sensitivity analyses: one only included studies with patients who didn’t have radicular pain or radiculopathy and the other only included participants aged 18-60 years, however these analyses followed similar trajectories to the main analysis,” said Dr Wallwork.

The research included 95 prospective inception cohort studies, and did not include experimental or interventional studies, or studies including people with conditions that might affect the trajectory of back pain, such as pregnancy and certain other comorbidities.

The study was a follow-up to a 2012 meta-analysis by the same research group, where patients were categorised as having acute back pain (less than six weeks) and persistent back pain (more than six weeks). They reported marked improvements in pain and disability in the first six weeks for both groups, and the findings informed international clinical guidelines for managing non-specific low back pain.

However, pulling out a “sub-acute” group from the “persistent” group in the current study has resulted in a more nuanced picture of the clinical course of low back pain, with the outcomes for people with persistent back pain a lot less favourable than previously thought.

“The current understanding that most individuals with a new episode of low back pain get better within two weeks may need reconsideration,” the authors wrote.

“Although most people with acute and subacute low back pain do see improvements early on, our updated meta-analysis shows that many continue to experience ongoing pain and disability.”

The authors suggested that the findings support the need for reassessment within the first three months after an episode of low back pain to identify and escalate care among those recovering slowly, describing it as “a critical focus of intervention”.

“For people who have pain that persists for 12 weeks or more, pain and disability remain high, which highlights the importance of developing better treatments for this group,” they wrote.

Canadian Medical Association Journal 2024, online 22 January