The causes of tremor range from benign conditions through to progressive neurodegenerative diseases

“My hand is shaking, doc, do you think it’s Parkinson’s?”

Tremor is common. So common, in fact, that most of us can probably think of a time when we have experienced a tremor in our hands or voice, perhaps during a time of stress.

What causes this mild, physiological tremor in otherwise healthy people? A few mechanisms have been identified. Mechanical tremor is an oscillation of an extremity (commonly a finger or hand) at its resonant frequency which is defined by the mathematical equation:

where K represents the spring constant and is governed by the stiffness/tone of the muscles attached to the extremity.1, 2

The kinetic energy driving this tremor is thought to come from cardioballistic movement and normal muscle tone. The resonant frequency of the tremor varies by body part, ranging from ~25 Hz for the fingers to 6-8 Hz for the hands, and even higher for more proximal joints such as the elbow (3-4 Hz) and the shoulder joint (0.5-2 Hz).1, 2

Muscle spindles and asynchronous firing of motor units within the muscles are also thought to play a role in the generation of physiological tremor. This tremor is usually very low in amplitude and seldom causes symptoms (stressful situations aside).

What are the causes of a symptomatic tremor?

DISEASES CAUSING TREMOR

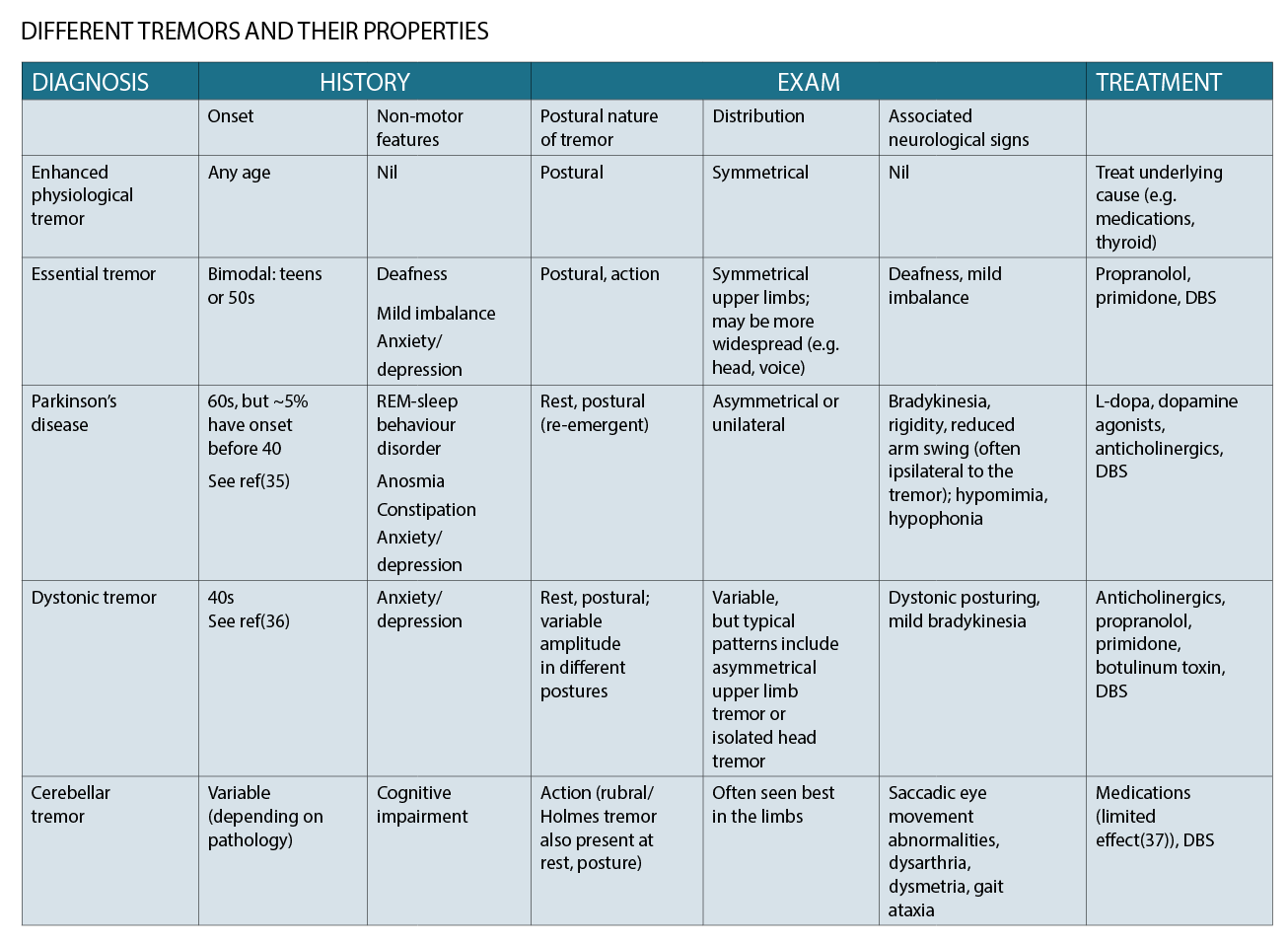

A number of diseases have been described as causing tremor, with the commonest and best known being essential tremor (ET) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). The table on page 28 provides a summary of a few common types of tremor and their properties.

These diseases range in terms of their anatomical localisation and pathology. Parkinson’s disease, for instance, is a neurodegenerative disease, while in the case of essential tremor the neuropathology remains controversial.

A common mechanistic feature of these tremors is activation of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network.3, 4 The existence of this common pathway among different tremors also helps explain how treatments targeting the thalamus (e.g. deep brain stimulation or MRI-guided focused ultrasound) can be effective for tremors of a number of different aetiologies, presumably by interrupting this network.

AN APPROACH TO ASSESSMENT

Keeping the above common syndromes in mind, the goals of the history and examination of tremor are to characterise the anatomical distribution and nature of tremor (frequency, rest versus postural, amplitude), look for clues as to the aetiology, and assess the functional impact.

Making a diagnosis is important both for treatment and prognostication, especially as the causes of tremor range from benign conditions (e.g. physiological tremor, essential tremor) through to progressive neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

HISTORY

Onset

It is important to clarify the age and affected body part at onset. If the hands tremble, was one initially affected or both? Patients with Parkinson’s or dystonic tremor will often recall clearly that one hand was initially affected (even if both are affected by the time of review). Patients with essential tremor, by contrast, will often report both hands shaking at onset.

Exacerbating and relieving factors

– Stress and social situations commonly exacerbate tremor, irrespective of the cause.

– Alcohol has been reported to give relief in many patients with essential tremor; alcohol intake is also relevant as patients with essential tremor may self-medicate with alcohol in order to suppress the tremor, leading to alcohol-related health problems.

– Past medications trialled and their effect.

Functional impact

This is often the most crucial part of the history in that it guides the approach to treatment.

How is the tremor impacting on the patient’s day-to-day life? It is important to enquire specifically about:

• Eating and drinking

– Using cutlery (e.g. soup from a spoon, peas on a fork)

– Drinking from a cup – one hand or two? Spills?

• Eating in public – since tremor is often exacerbated by stress and social situations, some patients will feel embarrassed to eat in public lest they spill food, and this can be a source of morbidity through limiting their social interactions.

• Writing – Are they able to write? Or sign their name?

• Work/hobbies – Does tremor interfere with fine motor tasks?

• Social impact – Is embarrassment about the tremor limiting their social life?

If a tremor is not causing significant functional impact, explanation of the diagnosis may be the only treatment that is required (and this is commonly the case for essential tremor in particular).

Medication history

Exposure to tremor-inducing medications should be screened for, including:5

• Antidepressants – SSRIs, lithium, amitriptyline

• Antiepileptics – valproate

• Beta-agonists – salbutamol, salmeterol

• Anti-dopaminergic medications – metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, haloperidol, tetrabenazine

• Immunosuppressants – tacrolimus, cyclosporine

• Anti-arrhythmics – amiodarone

• Hormones – thyroxine

• Drugs of abuse – alcohol, cocaine

Non-motor symptoms

Symptoms unrelated to tremor or movement can provide useful aetiological clues, and there is a growing appreciation of the non-motor phenotypes of different tremor syndromes.6

Some useful symptoms to screen for include:

– REM-sleep behaviour disorder – this is abnormal behaviour and muscle activity during REM sleep, classically consisting of acting out (often violent) dreams. The patient is often unaware and therefore the bed partner should be asked about violent behaviour while dreaming such as punching, shouting, or throwing oneself out of bed. This disorder has a very high rate of conversion to a synucleinopathy (such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, or dementia with Lewy bodies) and can be considered a prodromal symptom of these conditions that may anticipate the motor manifestations and diagnosis by many years.7

– constipation (also seen in Parkinson’s disease)

– anosmia (also seen in Parkinson’s disease)

– deafness (over-represented in essential tremor)

– anxiety/depression (over-represented in several tremor aetiologies)

Family history

It is useful to ask about a family history of tremor, Parkinson’s disease or dystonia.

This can be helpful both because of the hereditary nature of essential tremor but also if a relative has Parkinson’s disease it may be a clue as to the patient’s hidden anxiety regarding the cause of tremor.

Examination

• Inspect the patient seated with their hands in their lap

– Look for hypomimia

– Listen for hypophonia

– Look for rest tremor – this may only be seen if the patient is distracted (e.g. asked to say the months of the year backwards)

• Look for hand tremor with the hands in different positions:

– Arms outstretched, palms down

– Is there postural tremor?

– Is there re-emergent tremor? In PD the rest tremor often disappears upon stretching the arms out, and then re-emerges after a few seconds in this position.

– Finger-to-nose task – is there action tremor?

• Examine handwriting – is it small (PD)? Is there abnormal posturing of the hand/arm while writing (dystonia)?

• Look for tremor in other body parts – legs, head, tongue, voice, jaw.

• Look for bradykinesia and rigidity (PD)

• Examine the gait, looking for loss of arm swing, stooped posture, slow turning, and tremor in the hand while walking (PD); examine tandem gait to check balance.

What to document from the examination?

• Where is the tremor? Hands, legs, head, tongue, voice, jaw.

• What conditions bring out the tremor? Rest, action, and posture (+/- re-emergent)

• Any additional signs? Parkinsonism, cerebellar signs, etc.

INVESTIGATIONS

Investigations are often non-contributory, but occasionally can help clarify the diagnosis.

Bloods

• TFTs (hyperthyroidism can cause enhanced physiological tremor)

• Copper/caeruloplasmin (and 24 hour copper collection) – Wilson’s disease is a rare, but treatable, cause of movement disorders and present with an isolated tremor.8

Imaging

• MRI-Brain – this can sometimes reveal a structural cause e.g. in the case of rubral/Holmes tremor

Neurophysiology

• Neurophysiological tremor study – some tremor centres are able to perform specialised neurophysiological studies using surface electromyography (EMG) and accelerometry to measure quantitatively the frequency, amplitude, and other parameters of the tremor. These studies may be helpful in elucidating the diagnosis, particularly in difficult cases.9, 10

TREATMENT

Treatment of tremor is very much dependent on the cause, but as with most movement disorders, the main categories of treatment are oral medications, botulinum toxin, and deep brain stimulation.

Oral medications

We will discuss oral medication treatments for two of the commonest causes of pathological tremor: Essential Tremor and Parkinson’s disease.

Essential tremor

Beta blockers

Beta-blockers, propranolol in particular, have been used for several decades for the treatment of essential tremor. Their effect on reducing upper limb tremor is supported by randomised control trials.11-13

Effective doses of propranolol reported in the literature range from 120-240 mg per day, given in two or three divided doses for tolerability. Slow uptitration from a lower starting dose (e.g. 10mg twice daily) can be a useful strategy to minimise side effects.

Potential adverse effects include dizziness, fatigue, bronchospasm and bradycardia.

Primidone

Like propranolol, primidone is also effective for the treatment of essential tremor,14 but is less well tolerated and is therefore often used as a second-line therapy.

Doses of 125-500mg have been used in randomised control trials, and roughly a quarter of patients experienced an acute toxicity reaction to an initial dose of 62.5mg (consisting of nausea, vomiting, ataxia, and dizziness lasting one to four days).15, 16 In one study, doses above 250mg did not appear to confer any additional benefit.17

Parkinson’s disease

Tremor can be a more difficult symptom to treat in Parkinson’s disease compared to bradykinesia or rigidity, and appears to have a less clear relationship with the loss of dopaminergic neurons.18 The two main pharmacological categories of treatment are dopaminergic medications (e.g. levodopa) and anticholinergic medications.

Dopaminergic treatments

Tremor can often seem more resistant to levodopa treatment compared to bradykinesia and rigidity. Recent research suggests that the properties of the tremor can determine its response to treatment. For example, re-emergent tremor is effectively treated with levodopa, whereas non-re-emergent postural tremor is less responsive.19, 20 Higher doses of levodopa may be needed to achieve control of the tremor.21

Dopamine agonists such as pramipexole and ropinirole have also been proven to be beneficial in randomised control trials.22, 23 Care must be taken to screen for side effects, in particular Impulse Control Disorders (ICDs) such as gambling, internet addiction, sexual compulsions and excessive shopping.

Anticholinergic treatments

Anticholinergic medications (such as trihexyphenidyl) pre-dated levodopa in the treatment of Parkinsonian tremor. Research data suggest, however, that they are not as effective as levodopa and are more poorly tolerated, with neuropsychiatric and cognitive side effects in particular.21, 24, 25 Anticholinergics are sometimes used for the treatment of dystonic tremor, though RCT data is lacking.26

Botulinum toxin

Intramuscular injection of botulinum is used for the treatment of a number of neurological conditions, primarily dystonias (e.g. cervical dystonia, blepharospasm), spasticity, and hemifacial spasm. The botulinum toxin interferes with pre-synaptic release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junctions in the muscle it is injected into, weakening the muscle and giving some relief in many neurological conditions involving muscle hyperactivity.

In the case of tremor, botulinum toxin has a role in the management of dystonic head tremor and vocal tremor,27 and it should be noted that there is evidence that isolated head tremor is a form of cervical dystonia rather than a manifestation of essential tremor.28 There is emerging trial evidence for the use of botulinum toxin for upper limb tremor due to essential tremor or Parkinson’s disease,29-31 but in Australia botulinum toxin is not presently PBS-subsidised for this indication.

Deep Brain Stimulation

In patients with severe and disabling tremor refractory to medications, surgical treatments can be considered. The most commonly used surgical treatment at present is deep brain stimulation (DBS), which entails implanting electrodes to stimulate targets deep within the brain.

For tremor, the thalamic ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) is the most commonly used. While this treatment is used in various tremor types, there is long-term follow-up data to suggest a greater effect in parkinsonian tremor and essential tremor than in dystonic tremor.32

More recently, MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) has emerged as a non-invasive method of ablating a deep brain tremor target such as the VIM, and has been used successfully for both ET and non-ET tremors.33, 34

At time of writing, this treatment is not yet available in Australia.

REFERRAL

Referral to a neurologist is recommended when the diagnosis is unclear or for specialist input regarding treatment.

As previously mentioned, for mild essential tremor not causing any functional impact on activities of daily living, explanation of the diagnosis alone may be sufficient without any need for treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

• Tremor is a common problem.

• Focussed history and examination are most useful in determining the diagnosis; investigations usually have a lesser role.

• Screening for alcohol use and potentially causative medications (e.g. antiepileptics) is an important part of the history.

• Treatment is determined by the diagnosis and functional impact of the tremor; mild cases of essential tremor may not require any treatment beyond an explanation of the diagnosis.

• For severe tremor refractory to medications, non-pharmacological treatments such as Deep Brain Stimulation (and MRI-guided focussed ultrasound) have an important role in treating symptoms and restoring function.

Dr Alessandro Fois, BSc (Adv; Hons 1, Medal) BM Bch (Oxon) MRCP FRACP, is a Sydney-based neurologist with a special interest in movement disorders (such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia) and headache, migraine and general neurology.

Website:

//neurologycastlehill.com.au/dr-alessandro-fois

Disclaimer: This is an article that is written to inform medical practitioners and does not replace seeking appropriate medical advice from a professional medical practitioner.

References:

1. Deuschl G, Raethjen J, Lindemann M, Krack P. The pathophysiology of tremor. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24(6):716-35.

2. Stiles RN, Randall JE. Mechanical factors in human tremor frequency. Journal of applied physiology. 1967;23(3):324-30.

3. Timmermann L, Gross J, Dirks M, Volkmann J, Freund HJ, Schnitzler A. The cerebral oscillatory network of parkinsonian resting tremor. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 1):199-212.

4. Schnitzler A, Munks C, Butz M, Timmermann L, Gross J. Synchronized brain network associated with essential tremor as revealed by magnetoencephalography. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2009;24(11):1629-35.

5. Morgan JC, Kurek JA, Davis JL, Sethi KD. Insights into Pathophysiology from Medication-induced Tremor. Tremor and other hyperkinetic movements (New York, NY). 2017;7:442.

6. Fois AF, Briceno HM, Fung VSC. Nonmotor Symptoms in Essential Tremor and Other Tremor Disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2017;134:1373-96.

7. Dauvilliers Y, Schenck CH, Postuma RB, Iranzo A, Luppi PH, Plazzi G, et al. REM sleep behaviour disorder. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2018;4(1):19.

8. Jang W, Cho J, Kim JS, Kim HT. Wilson’s disease only presenting with isolated unilateral resting tremor. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38(6):939-40.

9. di Biase L, Brittain JS, Shah SA, Pedrosa DJ, Cagnan H, Mathy A, et al. Tremor stability index: a new tool for differential diagnosis in tremor syndromes. Brain. 2017.

10. Schwingenschuh P, Katschnig P, Seiler S, Saifee TA, Aguirregomozcorta M, Cordivari C, et al. Moving toward “laboratory-supported” criteria for psychogenic tremor. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2011;26(14):2509-15.

11. Calzetti S, Findley LJ, Perucca E, Richens A. Controlled study of metoprolol and propranolol during prolonged administration in patients with essential tremor. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1982;45(10):893-7.

12. Jefferson D, Jenner P, Marsden CD. beta-Adrenoreceptor antagonists in essential tremor. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1979;42(10):904-9.

13. Koller WC, Biary N. Metoprolol compared with propranolol in the treatment of essential tremor. Archives of neurology. 1984;41(2):171-2.

14. Haubenberger D, Hallett M. Essential Tremor. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;378(19):1802-10.

15. Findley LJ, Cleeves L, Calzetti S. Primidone in essential tremor of the hands and head: a double blind controlled clinical study. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 1985;48(9):911-5.

16. Koller WC, Vetere-Overfield B. Acute and chronic effects of propranolol and primidone in essential tremor. Neurology. 1989;39(12):1587-8.

17. Koller WC, Royse VL. Efficacy of primidone in essential tremor. Neurology. 1986;36(1):121-4.

18. Rossi C, Frosini D, Volterrani D, De Feo P, Unti E, Nicoletti V, et al. Differences in nigro-striatal impairment in clinical variants of early Parkinson’s disease: evidence from a FP-CIT SPECT study. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(4):626-30.

19. Belvisi D, Conte A, Cutrona C, Costanzo M, Ferrazzano G, Fabbrini G, et al. Re-emergent tremor in Parkinson’s disease: the effect of dopaminergic treatment. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(6):799-804.

20. Dirkx MF, Zach H, Bloem BR, Hallett M, Helmich RC. The nature of postural tremor in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2018;90(13):e1095-e103.

21. Jimenez MC, Vingerhoets FJ. Tremor revisited: treatment of PD tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012;18 Suppl 1:S93-5.

22. Navan P, Findley LJ, Jeffs JA, Pearce RK, Bain PG. Randomized, double-blind, 3-month parallel study of the effects of pramipexole, pergolide, and placebo on Parkinsonian tremor. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2003;18(11):1324-31.

23. Schrag A, Keens J, Warner J. Ropinirole for the treatment of tremor in early Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9(3):253-7.

24. Katzenschlager R, Sampaio C, Costa J, Lees A. Anticholinergics for symptomatic management of Parkinson’s disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2003(2):Cd003735.

25. Koller WC. Pharmacologic treatment of parkinsonian tremor. Archives of neurology. 1986;43(2):126-7.

26. Fasano A, Bove F, Lang AE. The treatment of dystonic tremor: a systematic review. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2014;85(7):759-69.

27. Fasano A, Bove F, Lang AE. The treatment of dystonic tremor: a systematic review. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2014;85(7):759-69.

28. Albanese A, Sorbo FD. Dystonia and Tremor: The Clinical Syndromes with Isolated Tremor. Tremor and other hyperkinetic movements (New York, NY). 2016;6:319.

29. Mittal SO, Machado D, Richardson D, Dubey D, Jabbari B. Botulinum toxin in essential hand tremor – A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study with customized injection approach. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2018.

30. Kim SD, Yiannikas C, Mahant N, Vucic S, Fung VS. Treatment of proximal upper limb tremor with botulinum toxin therapy. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2014;29(6):835-8.

31. Samotus O, Lee J, Jog M. Long-term tremor therapy for Parkinson and essential tremor with sensor-guided botulinum toxin type A injections. PloS one. 2017;12(6):e0178670.

32. Cury RG, Fraix V, Castrioto A, Perez Fernandez MA, Krack P, Chabardes S, et al. Thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor in Parkinson disease, essential tremor, and dystonia. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1416-23.

33. Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, Ghanouni P, Kim YG, Lee W, et al. A Randomized Trial of Focused Ultrasound Thalamotomy for Essential Tremor. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;375(8):730-9.

34. Fasano A, Llinas M, Munhoz RP, Hlasny E, Kucharczyk W, Lozano AM. MRI-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy in non-ET tremor syndromes. Neurology. 2017;89(8):771-5.

35. Nalls MA, Escott-Price V, Williams NM, Lubbe S, Keller MF, Morris HR, et al. Genetic risk and age in Parkinson’s disease: Continuum not stratum. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society. 2015;30(6):850-4.

36. Erro R, Rubio-Agusti I, Saifee TA, Cordivari C, Ganos C, Batla A, et al. Rest and other types of tremor in adult-onset primary dystonia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):965-8.

37. Labiano-Fontcuberta A, Benito-Leon J. Understanding tremor in multiple sclerosis: prevalence, pathological anatomy, and pharmacological and surgical approaches to treatment. Tremor and other hyperkinetic movements (New York, NY).2012; 2.