When education focuses solely on evidence, we can end up learning more and more about less and less.

As I face yet another year of compulsory CPD, I am thinking about the reasons why we humans tend to over-simplify life.

Medicine would be so much easier if Mother Nature read our textbooks and organised herself into whatever categories we determine are important. However, this is not how humans work.

No matter how we try to divide up the world into aliquots, many GP patients are likely to be the ones that slip through the classification net, and these are also the people who are excluded from clinical trials. They are the people that research rejects.

Uncertainty is uncomfortable, so there is a tendency to focus on the more concrete aspects of care in greater and greater detail, but put the unknowns to the back and not attempt to understand them at all.

When education focuses solely on evidence, we can end up learning more and more about less and less.

The lure of ‘best practice’

There is a great historical precedent for over-reliance on experts and systems, and it comes from anatomy.

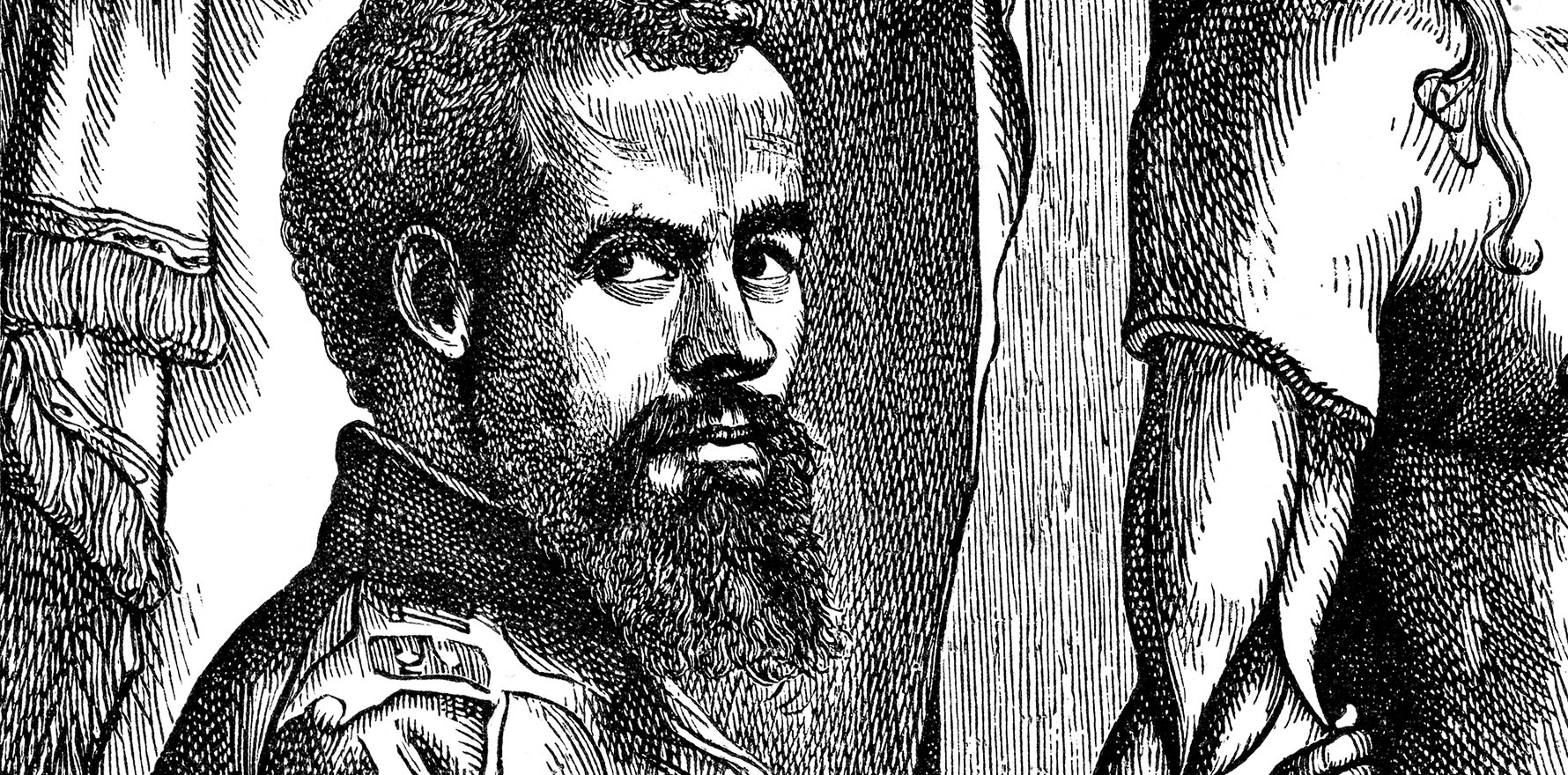

Galen was an ancient Roman anatomist, who learned most of what he knew from dissecting monkeys. Over the next 2000 years, his knowledge was cemented into a series of drawings and eventually a textbook, probably the longest lasting medical text of all time. By 1500, learning anatomy meant approaching a dissection with someone reading aloud from a Galenic textbook, with the dissecting technician searching for the evidence to support what Galen expected to find.

And then, in the great tradition of medical science, Italy produced an upstart.

In the 16th century, Andreas Vesalius was one of those kids who collected animal bones and lined them up on his windowsill for further study. He graduated at a ridiculously young age and became a professor of anatomy a day after graduating.

At the time, there was a unique opportunity at the University of Padua. The Pope decided that it was a rather good thing for artists like Leonardo da Vinci to be able to examine bodies in detail, and it probably did the medical profession no harm to be able to openly dissect bodies, rather than learning their anatomy from bodies in various states of decay stolen from tombs.

Six years after graduation, Vesalius had transformed teaching, using a dissector and an artist to document what they could actually see, rather than what Galen told them to find. His textbook, De humani corporis fabrica, transformed the teaching of human anatomy. It probably helped that the artists of the renaissance were rather good at representing three-dimensional objects, because the illustrations were a core feature of the learning.

Matching education techniques with educational aims

The rationale behind AHPRA’s insistence on “measuring outcomes” and “reviewing performance” activities for all doctors is a good one, but it’s like saying dissection is an excellent way of learning anatomy.

It depends on the goal, the way the teacher approaches the task and the way the learner uses it to meet their needs.

There are always doctors who are poor performers. These doctors may avoid examining their own practices, choosing passive forms of CPD, like sitting up the back in large lectures at professional conferences in nice places. In a way, they listen to someone reading out Galen.

Making them do particular forms of CPD may not help. I’m sure there are ways of remaining disengaged in any form of CPD. Educators offer opportunity, not magic.

The problem is that these doctors are a small, unrepresentative cohort in a large group of dedicated professionals who are life-long learners and care about their communities, who learn because it is a constant part of their professional practice.

Because people, and diseases, and techniques, and science, and expectations constantly change, we learn from our students, our patients, our peers and a whole lot of inputs that are hard to quantify — and that is the problem.

Some forms of learning are hard to squeeze into pre-defined boxes, which means we often have to do educational programs that are not really geared towards our educational needs. It’s irritating, often pointless, and sometimes a little bit soul destroying.

Educational theories and techniques are never universally “good”. An expert lecture may change my practice more profoundly than a poorly targeted audit. The reality of audits is that they address a small part of practice. The more diverse your practice, the less revealing they are.

Reviewing performance and measuring outcomes works best with a relatively homogenous population with definable and measurable outcomes. Think hip replacements, or cataracts, or well understood, common diseases like diabetes.

Quantifiable outcomes have little to say when we are trying to help people who would never have made it into any trial on which guidelines are based.

After all, “reviewing performance” needs an understanding of what “good performance” is. Without a gold standard we may review our performance and alter care to make it worse, not better.

Related

First principles

There is a business framework called the Cynefin framework which defines problems as simple, complicated, complex and chaotic.

Complex and chaotic problems need to be solved by going back to first principles, which brings me to the art of general practice. When a person isn’t getting better, it is important to think both in terms of biomedicine – am I missing something or is there a disease lurking below the surface – and in relational terms – is there something about this person I’m not understanding.

In a way, I think of this like Vasalius, using a scientist for the dissection and the artist for seeing what is really there.

Because AHPRA requirements are geared towards the scientific end of the equation, I’ve been working on finding ways of incorporating other ways of knowing into CPD, specifically for measuring outcomes and reviewing performance requirements.

I think it is important to understand the breadth of what we do, and focus on more than applying yesterday’s (biased) evidence to today’s diverse patients to improve health in tomorrow’s context.

Learning can involve improving compliance with established standards, but it also needs to be curious, open and critical. If you are interested in finding out more about addressing the art of general practice, not just the science, feel free to join my little CPD revolution at drlouisestone.com/cpd.

We should do more as GP learners than adhere and comply with pre-determined best practice. We need space to be the critical thinkers we are.

Professor Louise Stone is a GP in Canberra and an academic at Adelaide University. A collection of her research, policy and teaching materials can be found at drlouisestone.com.