What psychological factors drove two men to attempt to assassinate the mastermind behind the apartheid?

What psychological factors drove two men to attempt to assassinate the mastermind behind the apartheid in South Africa?

Here comes the story of the Hurricane

The man the authorities came to blame

For something that he never done . . .’

– Bob Dylan Hurricane

Assassination is the killing of a political figure (or celebrity) for political goals, although these can be muddled and confused. It is done by three types of people: firstly, by those operating on behalf of a political organisation or group; secondly, by individuals who represent no one but see their goal as political; thirdly, by individuals with overt mental illness who may rationalise their actions as political. Many assassins fall somewhere between the second and third categories, if not the first – the ‘lone nut’ assassins in American parlance.

There has been much debate about the mental state of assassins of John Kennedy, Martin Luther King and John Lennon, if not many other cases. To pursue this theme it is worth studying the two men who attempted to kill the high priest of apartheid, South African prime minister Dr Hendrik Verwoerd, succeeding on the second occasion.

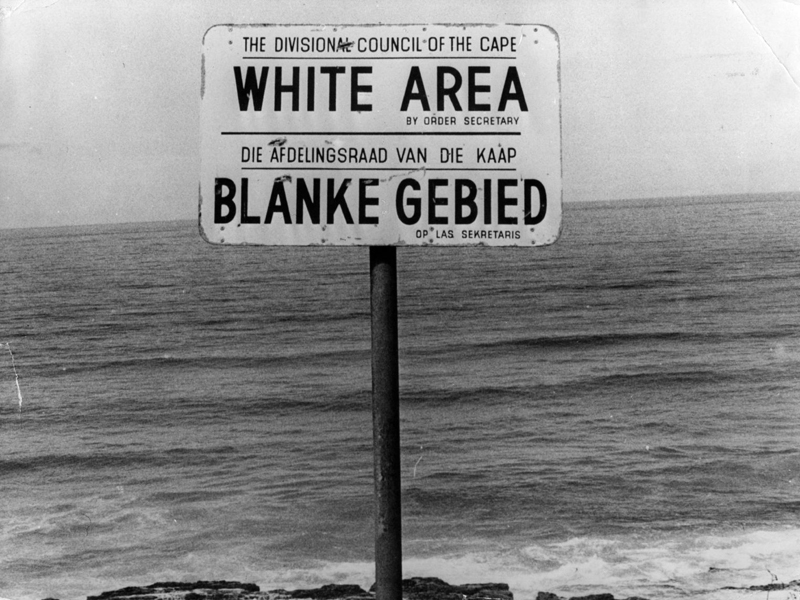

After he became Prime Minister in 1958, Verwoerd took Afrikaner nationalism to a new high, establishing the republic and leaving the Commonwealth. But shadows loomed. The Sharpeville massacre was an indication of the lengths to which the state would go to suppress opposition. Many whites worried – rightly as it turned out – that the outside world would become increasingly hostile.

One of these was David Pratt. Of English origin, his father was enormously wealthy. He had epilepsy from an early age and this led to bullying at school. His later life was turbulent with bouts of mental illness requiring hospitalisation in South Africa, England and America. He often experienced euphoria after a seizure, followed by auditory hallucinations, interpreting organ music in his head as heavenly messages, and spiritual delusions. In this state of mind he would engage in excessive spending, make reckless business decisions and grandiose religious claims.

Pratt owned four farms with a manganese mine and sold trout to restaurants. Two marriages failed and there was scarcely a time when he did not require treatment. Although he could be kind and charming, he was prone to violent and disruptive outbursts. Strongly opposed to Afrikaner Nationalism, Pratt was convinced that apartheid was ‘a monster’ that would drag South Africa backwards. The day before the Rand Easter Show in 1960 he thought: “This cannot go on. Where can we see any light?”

On 9 April he went to the Show where he had some trout exhibits, taking a revolver with him. He was to say “the feeling became very strong that someone in this country must do something about it, and it better bloody well be me, feeling as I do about it.” Verwoerd was to give a speech. He thought: “I shall not kill the man, but lay him up for a month or more to give him time to think things over.”

Pratt walked towards Verwoerd on the podium and shot him twice in the face at point-blank range. He was immediately arrested and taken into custody.

At court, Pratt said, “I won’t go through the shooting sequence, except to say that I felt a violent urge to shoot the apartheid – the stinking apartheid-monster gripping South Africa’s throat.” He interrupted the proceedings, saying, ‘I was shooting at the epitome of apartheid, rather than Dr. Verwoerd.’

The news of Verwoerd’s recovery struck him as miraculous and “It all fitted a pattern.”

The court accepted the reports by five psychiatrists that Pratt lacked legal capacity and could not be held criminally liable for having shot the prime minister. Pratt had manicdepressive disorder with a “psychotic saviour syndrome” and acted on the spur of the moment.

On 26 September 1960, he was committed to a mental hospital in Bloemfontein. A year later, he hanged himself on his 52nd birthday.

Miraculously surviving being shot reinforced Verwoerd’s messianic belief that he was the chosen leader: ‘I heard the shots and then I realised that I could still think, and I knew I had been spared to complete my life’s work’.

And he went on to try his best. The result was increased repression, the driving of the ANC underground, growing isolation and guerrilla incursions into South West Africa. Verwoerd was undeterred. There was no going back. The misery for black and mixed race people steadily increased.

Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all humankind sinned against me?

– Mary Shelley Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus

Dimitrios ‘Minis’ Tsafendas, epitomised the tragedy and contradictions of a racially segregated society. Officially classified as being of mixed race, born of the union with a Swazi woman with a Greek father in Mozambique, he was able to function at the lowest point in the crazy racial quilt that constituted South Africa. Despised and rejected, there was no family, no friends, no group with whom he could find acceptance.

There is a curious resonance between the lives of Tsafendas and Nelson Mandela, the freedom fighter and secular saint who was imprisoned for his political beliefs. Mandela, a scion of Xhosa royalty, gave up?family life and legal practice to fight for a free?society. Jailed for 27 years for treason against the?racist state, he never lost his dignity. By standing up for his beliefs and refusing to be intimidated, he won over his guards and waited out his opponents, who eventually lost the will to govern.

Like Mandela, Tsafendas, although poorly educated, was intelligent, perceptive and interested in the world. The Odyssean virtues of silence and cunning ensured his survival in exile and kept him moving. Like Ulysses, travelling as a sailor, he was destined to wander for decades until he was ineluctably drawn to the source of his pain and rejection. Fluent in a number of languages, he espoused a crude Marxism and believed in a free society. Constantly in trouble with the authorities and thrown in prison or psychiatric hospital, he managed to survive and move on to the next country including Mozambique, United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Germany and Portugal. Between 1943 and 1963 he was arrested five times, deported five times, twice incarcerated for long periods and eight times refused entry into South Africa.

When he did get back, Tsafendas returned to a land in the grip of a fanatic. Deeply resentful of the racial divisions that excluded him, he adeptly navigated the system to become a parliamentary messenger, his past not detected by those who hired him.

Oblige me by taking away that knife.

I can’t look at the point of it.

It reminds me of Roman history

– Stephen Dedalus in James Joyce’s Ulysses

The deed was done at 2.10 pm on 6 September 1966 when the House of Assembly about to convene the afternoon session. Verwoerd was expected to make an important announcement. Tsafendas walked over to his seat, leaning over as though he wanted to say something and stabbed Verwoerd four time before being overpowered by several members of parliament. Verwoerd died instantly.

Arrested, Tsafendas said that he had been told to kill Verwoerd by a tapeworm in his bowels.

All the psychiatrists who saw him agreed that he was insane and not accountable for his actions.

To the white folks who watched he was a revolutionary bum

And to the black folks he was just a crazy nigger

– Bob Dylan Hurricane

His trial was a farce, the judge saying ‘I can as little try a man who has not in the least the makings of a rational mind as I could try a dog or an inert implement. He is a meaningless creature’. He was found not guilty by virtue of insanity.

After the trial, the authorities wanted the whole situation to just disappear with too many loose ends to tie up, not least of which was why a man classified as mixed race with a criminal record espousing communism and a well-documented history of mental illness was allowed back into the country and employed as a parliamentary messenger. It occurred as a direct consequence of the irrational state policy; the system was set up to provide employment for Afrikaners who could not get work on their own ability. The incompetence that this brought about was the key issue in the mistakes that led up to the murder. It was all most inconvenient, authoritarian states not being very good at self-criticism. The tapeworm was an ideal scapegoat and no further questions needed to be asked.

Tsafendas was put in death row at Pretoria Central Prison, where he languished for three decades, being a nightly punching bag for the loutish prison guards, most of whom could scarcely remember Verwoerd or what he stood for.

With the end of apartheid, he re-emerged in people’s memories like a dusky incubus. Nelson Mandela arranged for him to be transferred to a mental hospital where he regained some dignity. He lived long enough to see the new South Africa, free of restrictions on mixing of the races, although it is doubtful whether it made much impact on him. He died in October 1999 and is buried in an unmarked grave in the cemetery alongside Sterkfontein Hospital.

For Tsafendas, the tapeworm that infested his bowel assumed mythical qualities, a crazy inversion of the South African obsession that said that because there was something wrong with him on the outside (the colour of his skin), there was something wrong with him on the inside. The commanding nematode drove him to find a solution to the problem; if he could not silence its voice, then he would kill the man who epitomised the racial purity that made him a pariah in his own land.

In all likelihood, as Tsafendas had periods of catatonia, depression, thought disorder and depersonalisation, in addition to thought disorder, hallucinations and delusions, his illness would be formally diagnosed as chronic paranoid schizophrenia.

But another possibility, if only to be excluded, suggests itself to the phenomenologist, an odd condition with a marvellous title: monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (MHP), a.k.a. delusional parasitosis or dysmorphobia. MHP is the delusional belief that something is wrong with your body; e.g. your nose is too big, your genitals are mis-shaped, parasites crawl under your skin. It is a form of paranoia, a group of illnesses that change or wane, but never disappear. MHP patients haunt dermatology and urology clinics, begging for special investigations and surgery that will correct their deformity or infestation. As many doctors have found to their cost, surgery on such patients does not relieve their concerns, but leads to renewed treatment seeking.

With Verwoerd dead, once ritual obeisance was over, the government could not wait to distance themselves from him. High Apartheid was finished and despite the rhetoric, it was never more than white supremacy that remained. It staggered on until 1994 when, to everyone’s relief, the game was up.

By then Verwoerd was long forgotten. He remains a curiously one-dimensional figure, easy to despise but difficult to understand. Like Hitler and Stalin, he was an outsider to some extent, having been born in Holland and over-compensated to establish his Afrikaner credentials. An intellectual giant who trained in Germany and the USA, he founded social psychology and sociology in South Africa. He is central to the development of the apartheid state and the definitive biography remains to be written. An unrepentant, if not fanatic ideologue, he was responsible for establishing the system of racial separation that uprooted the lives of millions of people.

Assassination is surprisingly rare in African politics. Verwoerd was a political phenomenon one can only hope will never be repeated. It gives some idea of the passions he aroused that there were such attempts on his life. Pratt, driven by a grandiose impulse he could scarcely understand, was but a myrmidon of what was to come. Then, with four furious thrusts of a hunting knife, Tsafendas joined the ranks of those fringe characters who have succeeded in changing the course of history, among whom Gavrillo Princip and Lee Harvey Oswald are the principal figures.

Robert M Kaplan has a section on assassinology in his new book, currently destined by the enemies of publishing promise never to see the light of day.