Identification and rapid referral and treatment of symptomatic patients is critical to reduce the risk of recurrent strokes

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the Western world and the principal cause of permanent neurological disability, with more than half of all stroke survivors remaining dependent on others for everyday activities.

Up to 85% of all strokes are due to ischaemia, but in up to a third of these, a definite cause is not identified. Approximately 20% of ischaemic strokes will affect the vertebrobasilar territory, and 80% the carotid territory, of which approximately half will be due to extra-cranial carotid disease.

The rest will be due to small vessel disease of the brain, cardio-embolic disease or other rarer causes.

Carotid-related ischaemic strokes are perhaps the most amenable to treatment to prevent further major strokes or death.

The greatest stroke risk, however, occurs in those with previous neurological symptoms, amaurosis fugax, transient ischemic attack, or previous stroke.

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for stroke, both ischaemic haemorrhagic.

The Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists have convincingly demonstrated that symptomatic patients with a carotid artery stenosis of greater than or equal to 70% benefit from carotid endarterectomy (CEA).

The benefits of intervention from surgery for asymptomatic carotid stenosis is controversial, but Level A evidence suggests that selected patients with a high-grade stenosis will benefit from stroke prevention measures directed to their carotid disease. This is more so in men than in women, in patients younger than 75 years of age, and with a life expectancy of more than five years.

Risk factor management for secondary prevention is essential, and vascular risk has been shown to decrease with treatment of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, smoking cessation and antiplatelet drug treatment.

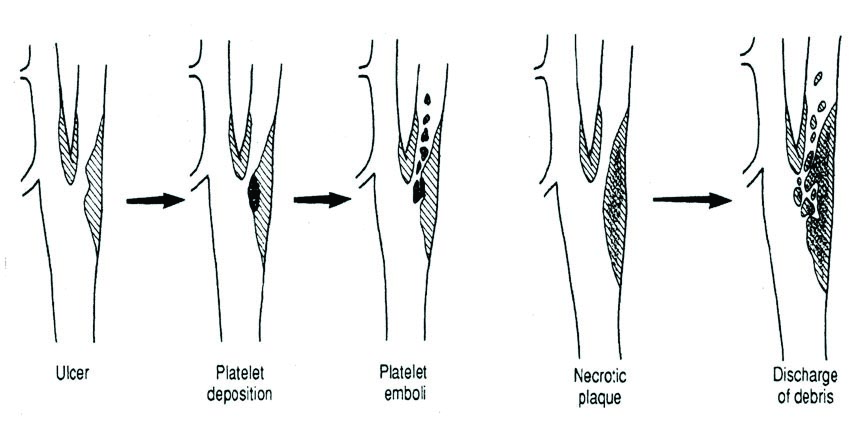

Figure 1: Pathophysiology of an ulcerated plaque, and plaque rupture in carotid artery disease, resulting in distal cerebral embolisation

Patho-physiology and risk factors

Atheroma is formed frequently at sites of arterial branching and turbulent blood flow, causing injury to the vascular endothelium as a result of haemodynamic shear stress. Endothelial injury leads to infiltration of macrophages laden with fat (“foam cells”), followed by a proliferation of smooth muscle cells and an extracellular matrix, covered by a fibrous cap.

Persistent injury results in an increase in the size of the atheroma and subsequent reduction of the vascular lumen. The progressively increasing size of the lesion may make it “unstable”, with a high degree of activated inflammatory cells and a large lipid core.

Rupture of the fibrous cap exposes circulating blood to the thrombogenic elements of the atheroma, forming platelet aggregates and localised thrombus, or even resulting in arterial occlusion. Distal thromboembolism, from rupture of the carotid plaque, to the intracranial vessels may result in an embolic stroke. (Figure 1)

Carotid atherosclerosis is prevalent in patients with disease in other vascular territories e.g. coronary or peripheral vascular disease.

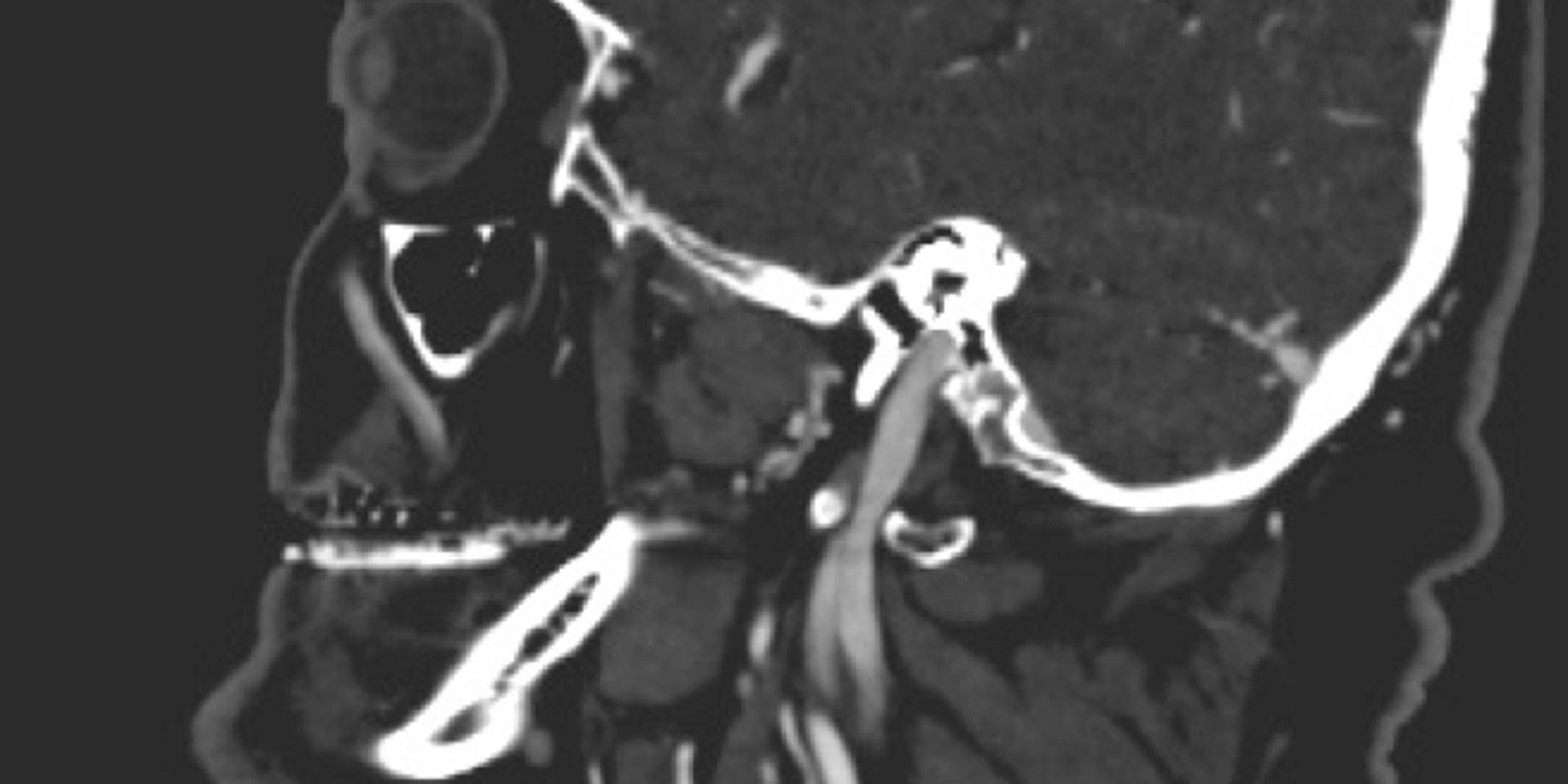

The risk factors for carotid atheroma are therefore the same as for all atherosclerosis. And the classical risk factors for stroke include hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and diabetes, smoking and advancing age. Age is an independent risk factor for carotid artery stenosis, and in the general population, the overall prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis (Figure 2a) greater than 50% is estimated at 2% to 9%. The incidence increases to 5% to 12% in patients older than 65 years of age, and is even higher in patients with other arterial disease.

This is estimated at 11% to 26% in patients with coronary artery disease and 25% to 49% with peripheral artery disease.

Hypertension is the most important risk factor for stroke, both ischaemic and haemorrhagic, and management of hypertension considerably reduces coronary and stroke risk.

The obesity epidemic directly increases the risk factors for stroke including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycaemia.

Diabetes mellitus itself also ranks highly as a risk factor for stroke. Rigorous control of blood pressure and lipids is recommended in patients with diabetes.

Tight glucose control should be the goal among diabetics with ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack to reduce microvascular complications.

Hyperlipidaemia is a risk factor for stroke, and stroke-risk may be reduced by the use of statins, as demonstrated in patients with coronary artery disease in studies such as the SPARCL trial and the Heart Protection Study.

The carotid artery can easily be investigated with Doppler ultrasound, and changes to the intima-media thickness of the vessel wall may serve as a marker of generalised vascular health. Composition, structure, and inflammation of the plaque in a carotid artery are important factors in determining the stroke risk of someone with carotid artery stenosis.

There is a strong association between smoking and stroke risk.

The duration and quantity of smoking plays a key role in stroke risk and the development of atherosclerosis, and coexisting vascular risk factors also influence stroke risk in synergy with smoking. Current smokers have at least a two to four times increased risk of stroke compared with ex-smokers. This risk increased to six times when this population was compared with non-smokers.

The carotid intima-media thickness in patients attending a lipid clinic was highest in current smokers, lower in ex-smokers and lowest in non-smokers (p < 0.0001).

The exact triggers that convert a stable plaque to an unstable plaque are unknown.

Carotid intima-media thickness was positively related to the number of cigarettes smoked and duration of smoking, and held true for ex-smokers and current smokers (p < 0.0001). There were no differences for those smokers of cigarettes with high or low nicotine, tar or carbon monoxide content (p > 0.05).

Progressive carotid narrowing may also be due to intimal hyperplasia, which can occur after radiation treatment to the neck or prior carotid endarterectomy.

The unstable plaque

Plaque may be heterogeneous, echodense and calcified, and can be formed by the homogenous deposition of cholesterol. Specific features of an atherosclerotic plaque may represent an unstable plaque and one that is prone to rupture, and for carotid stenosis, precipitate a stroke.

A vulnerable plaque includes a lipid core with a thin fibrous cap, and superficial ulceration. Plaque rupture causing endothelial disruption, platelet aggregation or thrombus formation are important mechanisms predisposing to embolic cerebral infarcts and acute ischaemic stroke. Inflammation in the plaque wall has been postulated to influence thrombus formation in myocardial infarction (MI) as well as stroke.

However, the exact triggers that convert a stable plaque to an unstable plaque are unknown. (Figure 1)

Symptoms of carotid disease

At risk patients are warned to use the B.E.-F.A.S.T. acronym to recognise the symptoms of stroke, and to monitor for Balance, Eye symptoms, Facial weakness, Arms or leg symptoms or weakness, Speech abnormality and Time from the event (to act quickly).

Dizziness, collapse and visual symptoms may be signs of global cerebral ischaemia, because the brain is hypo-perfused. Amaurosis fugax or “fleeting blindness” is a transient loss of vision when a clot is lodged in the retinal vessels, patients frequently present to ophthalmologists with scotoma, flashing lights or a temporary or permanent loss of a part of the visual field, and cholesterol emboli may be identified on fundoscopy.

A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is defined as a focal neurological deficit that may be either sensory or motor and resolves completely within 24 hours. It may be due to a small embolic clot from the carotid artery that lodges in a particular area of the brain.

The size and site of lodgement of the clot determines the presentation for e.g. weakness or tingling in the arm or upper and lower limbs.

Dysphasia, either expressive or receptive, and speech deficits is a symptom of left hemispheric TIAs.

Symptoms of stroke are similar to those of a TIA, however a “mini-stroke” is when patients have symptoms of an attack that recovers completely but takes longer than 24 hours. A major stroke or cerebrovascular accident occurs when symptoms do not resolve within a few days, and is due to infarction of a portion of the brain due to loss of its blood supply, and can result in severe disability or death.

Evaluation of a carotid stenosis

A carotid artery stenosis can sometimes be identified by the detection of a bruit, representing turbulent flow, with a stethoscope to the neck on clinical examination. Further evaluation can be performed with imaging tests that diagnose, localise and evaluate the carotid stenosis.

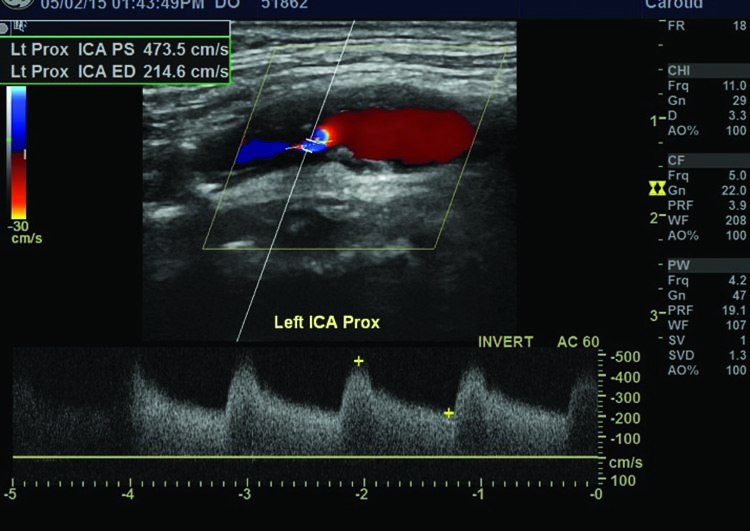

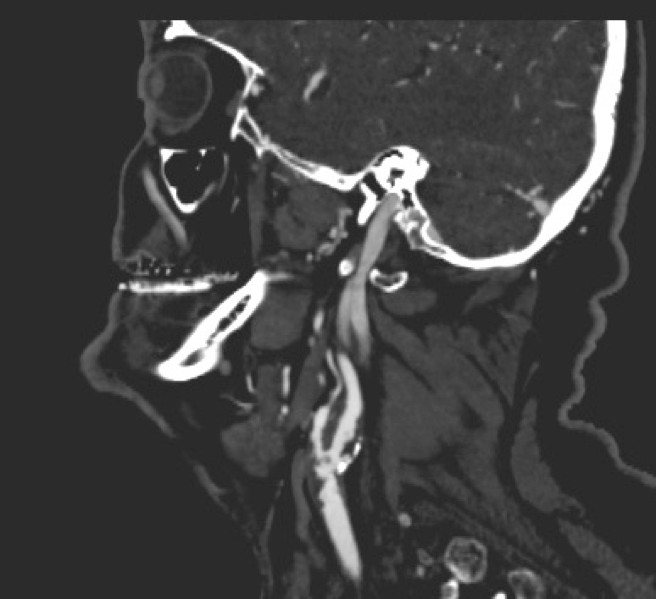

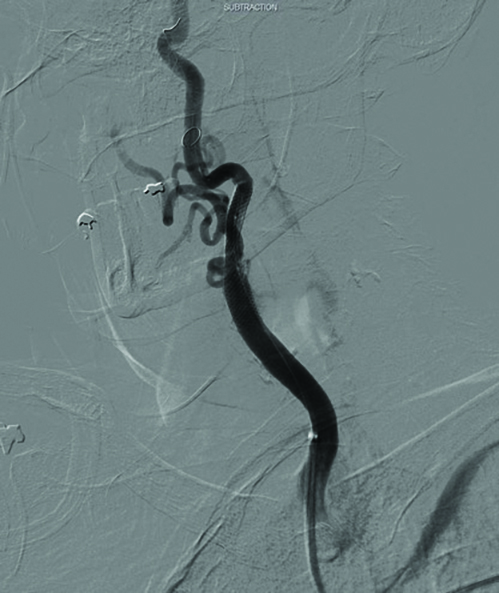

These imaging modalities include carotid duplex (Doppler ultrasound), non-invasive vascular ultrasound; computerised tomography angiography (CTA), which involves the administration of intravenous contrast to produce and assess detailed pictures of arteries anywhere in the body using ionising radiation; magnetic resonance angiography, which produces pictures similar to CTA and may involve the administration of contrast but avoids ionising radiation; and formal digital subtraction angiography, when contrast material is injected into the arteries, and a special X-ray image is captured. (Figures 3a, 3b and 3c)

Doppler ultrasonography is an excellent first-line non-invasive investigation after identification of a carotid bruit.

Using grey-scale imaging, it can uniquely measure intima-media thickness – a biomarker for atherosclerosis – and characterise plaque for plaque morphology related to the risk of stroke. Ulceration of carotid plaque can be identified on ultrasound, and is one of the strong predictors of future embolic events.

Systolic and diastolic velocity measurements correlate with the degree of arterial stenosis. Intima-media thickness can be reliably measured during carotid ultrasound, and an increasing ratio is a predictor of cardiovascular risk. (Figure 3a)

A simple non-invasive vascular ultrasound will identify a significant carotid stenosis, and is the first-line investigation.

Interventions

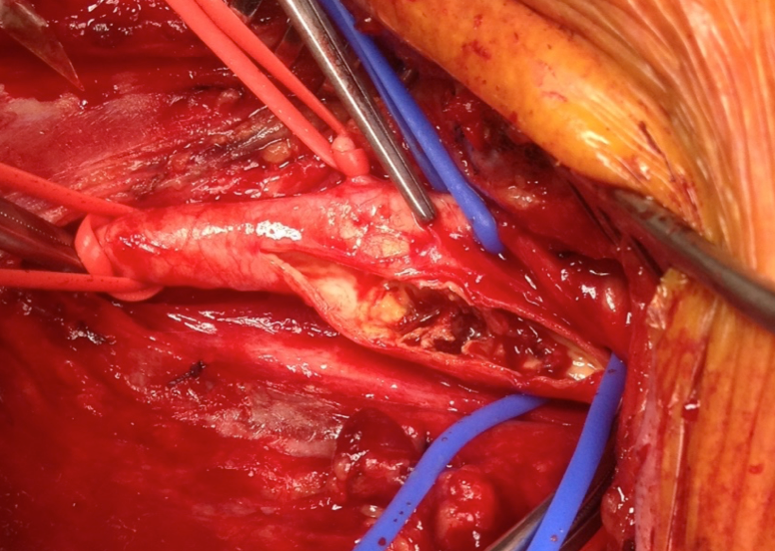

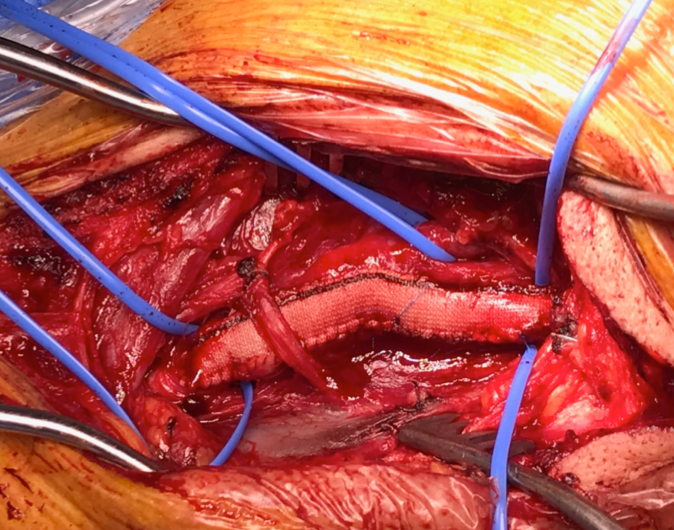

Since the 1950s, carotid endarterectomy has been the treatment of choice for high-grade symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Since then, the technical results of surgery have been further improved with the use of an arterial patch, and carotid endarterectomy can also be done under local or general anaesthesia.

The rapid advancement of endovascular technology has adapted endovascular techniques for carotid stenting using neuro-protection with distal filter devices or flow reversal techniques. Although the gold standard is currently carotid endarterectomy and patch, rapid improvement and evolution of endovascular devices may make carotid artery stenting more widely applicable.

Asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis and medical management

Medical management, and the initiation of secondary prevention therapy is generally considered as first-line therapy in asymptomatic patients with a less than 70% carotid stenosis, based on non-invasive ultrasound criteria.

Medical management may also be considered to be definitive therapy for selected patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis.

Medical management involves the use of an antiplatelet agent, and aggressive management of risk factors, including smoking cessation, hypertension, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia. Aspirin is the antiplatelet agent of choice, but dipyridamole, or clopidogrel or ticlopidine, or combination drugs are alternatives. Patients already on formal anticoagulation such as vitamin K antagonists or the newer direct Factor Xa inhibitors can continue on this treatment.

Lifestyle modifications and increased physical activity are important adjuncts. The benefit of surgical intervention for asymptomatic carotid stenosis is unclear. In the interventional surgical trials, benefit from carotid endarterectomy for selected patients with high-grade stenoses was seen in men more than women, and in patients less than 75 years of age, and with a life expectancy of more than five years.

(Figure 4a)

Symptomatic carotid artery stenosis

The triggers that activate an asymptomatic carotid plaque to become symptomatic remain unknown, but the relationship between the severity of stenosis and the risk of stroke is well established.

Symptomatic patients who experience symptoms from a carotid-related cerebral event should undergo carotid endarterectomy if the ipsilateral carotid stenosis is greater than 50%, and rapid referral to a vascular surgeon or neurologist is highly recommended.

The single most important issue for symptomatic carotid interventions is rapid treatment and there is now a concerted drive towards treating symptomatic patients as soon as possible after onset of symptoms, as a greater proportion of patients will die or suffer permanent disability through delayed interventions. Urgent carotid endarterectomy (less than two weeks) for evolving symptoms has a higher risk of procedural stroke than for stable symptomatic patients, but prevents more strokes.

Early intervention for symptomatic carotid stenosis remains a challenge for carotid artery stenting, but stenting outcome may be equivalent to carotid endarterectomy for younger patients, and may be a more suitable option for older patients. Stenting may be an alternative in patients with anatomical challenges for endarterectomy, e.g. very high lesion, close to the base of the skull, prior neck irradiation or prior neck surgery or carotid endarterectomy. Despite the technological advances however, carotid endarterectomy can still be performed with less risk than stenting. (Figure 4b, Figure 5)

Antiplatelet therapy should be initiated preoperatively if possible to minimise the post-operative risk of complications, and risk factor management is essential. Patients who experience a major stroke and present at a tertiary hospital within a few hours of the event may be a candidate for intravenous cerebral thrombolysis, which may reduce the severity of ischaemic stroke and significantly improve outcomes, and possibly allow definitive subsequent surgical intervention.

Concurrent carotid and coronary artery stenosis

Patients with combined coronary artery and significant carotid disease have better outcomes with staged rather than combined coronary artery bypass and carotid endarterectomy. The perioperative stroke, MI, and death rate of combined coronary and carotid surgery is 9% to 12%.

Therefore, the combined procedure is usually recommended for patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis and critically symptomatic coronary artery disease only. There is probably no benefit to be gained for combined carotid intervention for high-grade asymptomatic unilateral stenosis.

Bilateral carotid artery stenosis

In asymptomatic patients found to have bilateral carotid stenoses greater than 70%, the higher-grade stenosis, or the dominant hemisphere is generally treated first if the patient meets the criteria for intervention. If a patient is symptomatic on one side and found to have a asymptomatic contralateral carotid artery stenosis, the asymptomatic carotid stenosis is treated based on the merits of that stenosis.

Carotid restenosis

A high-grade stenosis noted after a prior carotid intervention is uncommon and generally a consequence of neo-intimal hyperplasia within the first two years after surgery, or new atherosclerotic plaque when it occurs beyond two years after surgery.

There is a very low risk of embolic stroke associated with neo-intimal hyperplasia and re-intervention is reserved for symptomatic patients.

Referring to a vascular surgeon

All patients with high-grade asymptomatic carotid stenosis and those with focal neurological deficits referable to the carotid or vertebral circulation, including visual deficits, transient ischaemic attacks, and mini-strokes or strokes with good recovery, should be referred for a full vascular assessment by a vascular surgeon. Full medical management and risk factor modification should be initiated in all patients.

The most important factor for symptomatic patients is identification, and rapid referral and treatment to reduce the risk of recurrent strokes, and to minimise the severity of the cerebrovascular accident. A simple non-invasive vascular ultrasound will identify a significant carotid stenosis, and is the first-line investigation.

Associate Professor Irwin V Mohan is vascular and endovascular surgeon at Northern Endovascular Specialists, Dee Why, and the University of Sydney