Female GPs are financially punished for doing the hardest work. Even the most resilient break under enough pressure.

Recently I was asked to put in a research proposal to address sexual harassment in medicine.

It’s an area I feel strongly about, and I have spent the last 10 years undertaking research in this area, including leading an international multi-author book. There is a lot of evidence, and at the moment I’m a bit of temporary expert.

I was suggesting we should undertake more research in specific areas to better understand how best to prevent this sort of harm. The senior public servant I was speaking with was keen to help, but put in some stipulations. “Just make sure you focus on solutions,” she said. “I need to hear more from GPs than the usual complaints from whining women.”

I wish I’d felt surprised, but I really wasn’t. It’s something female GPs put up with a lot. I am weary of meetings where I’m stuck in the middle, with female nurses accusing me of being patriarchal and non-collaborative, and senior male doctors, usually not GPs, telling me I don’t understand what general practice is actually like.

When I’m frustrated, I’m accused of “whining”. When I talk about the wellbeing of GPs, I’m told they “lack resilience”. It’s relentless and exhausting.

Do GPs have something to whine about?

GPs report declining job satisfaction, unsustainable workloads and increasing financial stress. Complex regulatory changes and increasing administrative requirements are particularly damaging. Fear of regulation is increasing. GPs report high rates of moral distress, feeling unable to protect patients from harm in a healthcare system under increasing strain. There has also been an increase in occupational violence that disproportionately affects women GPs, leaving them feeling physically and psychologically unsafe.

Internationally, rates of burnout, depression and abuse continue to rise. A survey of 10 high-income countries by the Commonwealth fund in 2022 shows over 50% of older physicians in most countries reported they would stop seeing patients within the next three years, leaving a primary care workforce made up of younger, more stressed, and burned-out GPs.

In the UK, GPs have faced increasingly negative press, portrayed as “clinically incompetent and morally deficient”. “While journalists and columnists are portraying themselves as the patients’ champion,” writes one author, “they need to realise that these relentless attacks have a much deeper impact. They can demoralise GPs to the point that they dread going to work or hasten their decision to leave the profession.”

There is a limit to anyone’s endurance. Standing there a copping a tirade of abuse from patients, media and other health professionals isn’t being “professional” or “resilient”, it’s being a doormat or a punching bag.

Do women have more reason to whine?

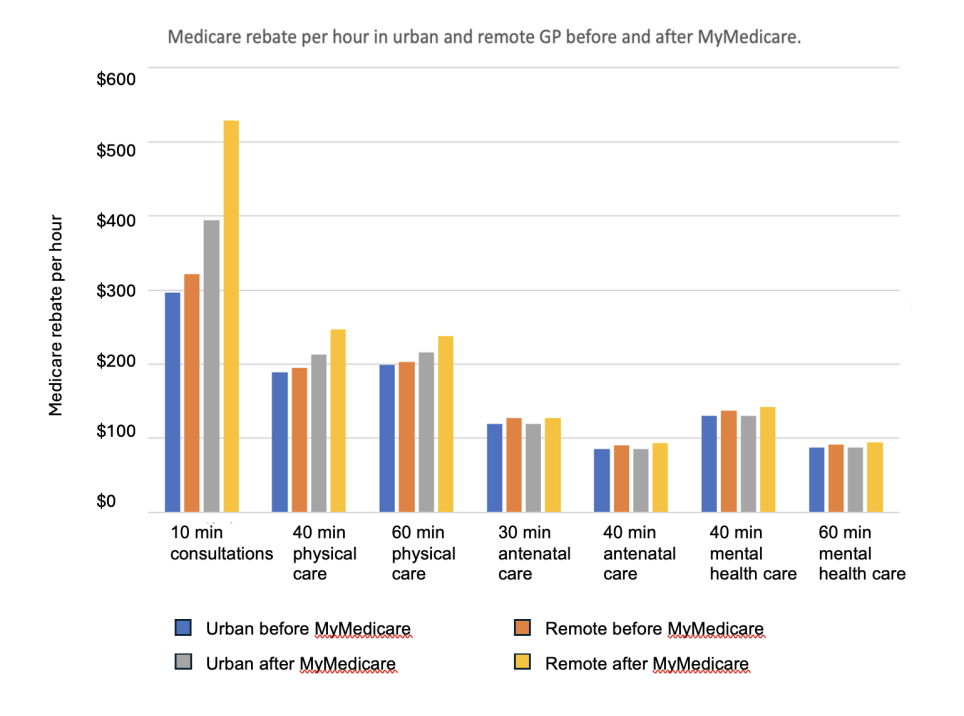

In Australia, female GPs have always had longer consultations, and a greater proportion of their work involves managing patients with mental illness and complex chronic disease. It wouldn’t be a problem if they weren’t financially penalised for doing the hardest work in the system.

The usual pushback is that we should have “better boundaries”. This is, of course, code for moving complex patients out of our appointment books, which many of us are not prepared to do for ethical reasons. We wouldn’t have to have “better boundaries” against less lucrative patients if there wasn’t a penalty placed on “women’s work”.

Recent policy changes have worsened this divide.

GPs have one of the highest gender pay gaps in healthcare. Based on taxable income, the pay gap is currently around 40% which explains why female GPs cite financial stress as a major concern. The following graph shows the total pay gap, but also the gap per hour, calculated from taxable income and hours worked.

Mayson and Bardoel in their qualitative study of female GPs outline the community expectations of women, and how this affects the work that they do. Healthcare is characterised as a caring profession, but “lady doctors” are assumed to care as a vocation, in which they have innate capacity and find personally fulfilling. They are seen as the best source of time and empathy.

This is not true, of course, with plenty of male GPs demonstrating similar skills. However, we live in a gendered world with gendered expectations where patients make gendered choices. The result is predictably unfair. Mayson & Bardoel describe seven key characteristics of female GP work.

- Physically and emotionally demanding part-time work, with a “second shift” of physical and emotional labour at home

- Poorly remunerated and invisible labour, with gendered remuneration structures

- Wanting to practice high-quality, slower medicine

- Trading off income for flexibility to accommodate uneven expectations of domestic labour and availability

- Internalised and external assumptions from health professionals and community characterising female GPs as expert in particular forms of caring, including treating psychological trauma

- Pressure from patients to donate time and reduce fees

- Portfolio careers, incorporating jobs with non-clinical or procedural elements with better pay to offset the cost of clinical work

So do the sensitive snowflakes just need to toughen up and stop whining?

There is a fabulous cartoon about the NHS, with an exhausted doctor talking to a bureaucrat about the wellbeing of his colleagues. “I’ve given them a room to cry in,” says the bureaucrat. “What more do they want?”

Related

The resilience narrative places the responsibility for wellbeing firmly on the shoulders of the individual. Our code of conduct reinforces this, putting wellbeing into AHPRA’s manual of professional expectations. I understand the idea, but it’s a curious choice. It implies we are responsible for our own health, even when there are systemic reasons to make wellbeing almost impossible.

The resilience narrative talks about the idea of being able to “bounce back” from adversity. However, a ball’s ability to bounce is not just about the characteristics of the ball, it’s also about the surface. Even a superball can’t bounce in a swamp. Nevertheless, attempts to push back and ask for the swamp to be drained inevitably lead to questions around resilience. It’s a convenient narrative that shifts responsibility from policy makers to GPs.

Female GPs constitute a particularly vulnerable workforce with multiple systemic barriers to sustaining a psychologically safe, financially viable and personally fulfilling career. With rising rates of mental illness and complex chronic disease in the community, the burden of care on women GPs is increasing exponentially. Sustaining this critical workforce will require a deeper understanding of their contemporary needs, and the threats to their wellbeing.

Maybe they have a reason to “whine” and maybe listening to them might help rehumanise an impossible system.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.