Current strategies are not effective in addressing the core issue, say respondents.

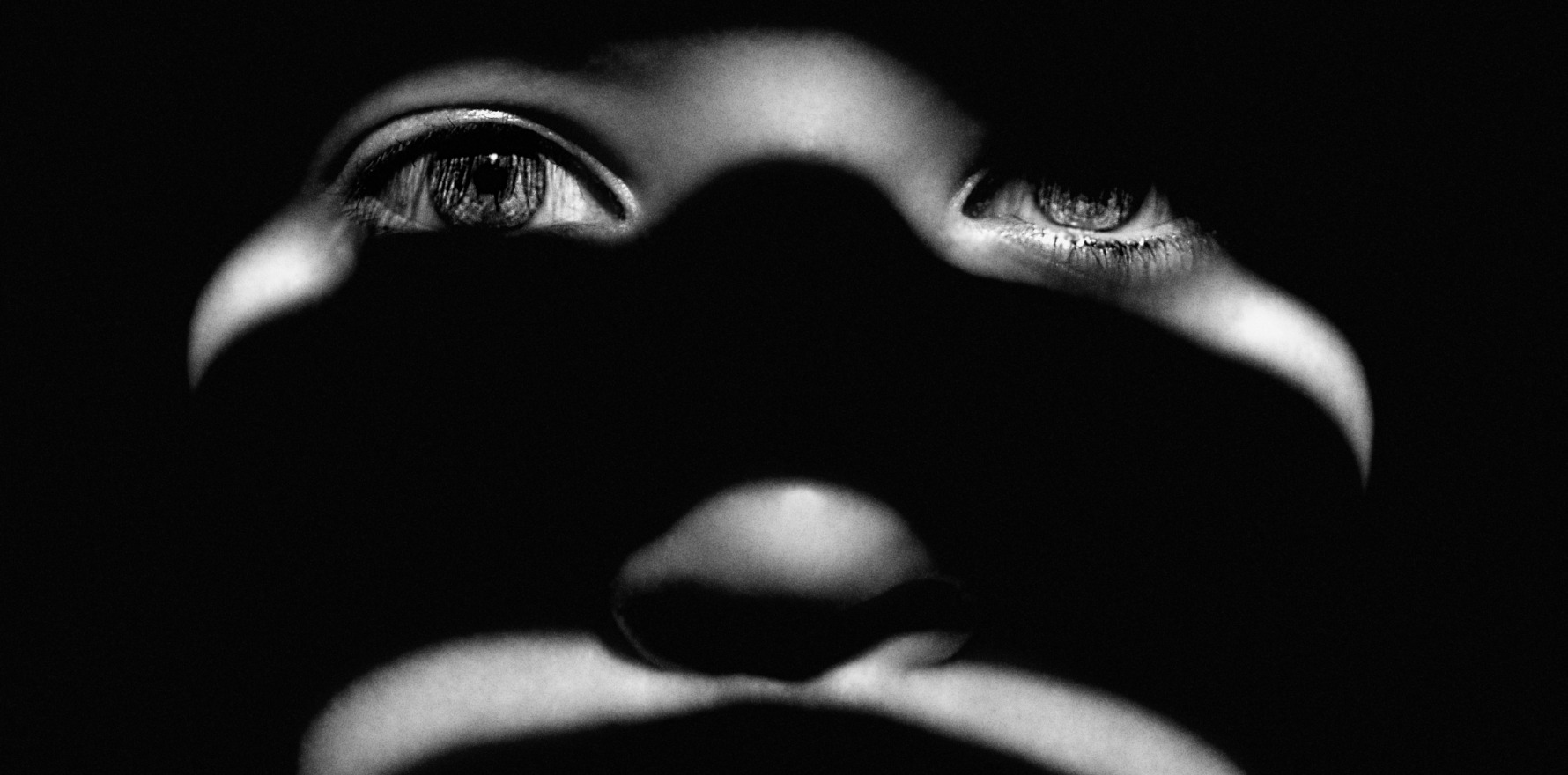

A recent national survey has highlighted concerning statistics on domestic violence, revealing that nearly 45% of participants reported experiencing a form of intimate partner violence.

The survey found that current national intimate partner violence prevention strategies have not yet achieved their objectives.

This has warranted calls for a strengthened long-term approach to domestic violence taking preventive measures, especially regarding support within social and economic conditions.

Three types of violence were addressed in the survey, with the most commonly reported form being psychological violence at 41.2%, followed by physical at 29.1% and sexual at 11.7%.

Analysis across age groups within the survey displayed a consistent prevalence of intimate partner violence, indicating that the issue remains a consistent problem in Australia.

Women were highly represented in the statistics with more women reporting experiences with each type of violence at 48.4% of participants, compared to men at 40.4%.

Regarding where general practice can assist with ending domestic violence, some are saying that general practice should not be seen at the same degree of responsibility as law enforcement.

“What you don’t want is GPs being used as duct tape,” Professor Louise Stone, women’s health researcher and GP, told TMR.

“Duct taping is about trying to make up for the deficit for the complex system by using general practice to fill in the gaps.”

Related

GPs evidently have the skills to address the direct health elements of domestic violence, but are not adequately trained or equipped well enough to address domestic violence’s other elements.

Medicare item numbers for domestic violence also raised concerns about how the listed mentions of domestic violence could endanger victims who may be in financially coercive situations.

Occupational violence was also an area of concern, especially for more isolated practices that would compromise the safety of GPs from aggressive partners.

“There’s also the consistent moral harm of being used in the system to ‘plug gaps’ when you actually can’t,” Professor Stone said.

Professor Stone elaborated on how general practice should not be used for advocacy, due to its inefficiency, as it would again be a “duct-tape” approach for a much larger issue.

“I think we should have a whole new area of the curriculum that addresses that concern and makes sure GPs are well placed to do this work,” she said.

A key argument within general practice’s involvement in domestic violence prevention is that domestic violence is firstly a crime before it is a health issue.

“I’ve got that is our job, however, I don’t think it’s our job to fix the underlying problem,” said Professor Stone.

“We just have to be careful that general practice is not being used to duct tape everyone else’s responsibilities together.

“We should be caring for women and families; we should be detecting domestic violence.

“We should be focusing on the medical care, not the social care, not that we should abandon people, but you can’t ask general practice to keep subsidising social care.”