Medical facilities and doctors in Syria are being repeatedly targeted in order to harm civilians

The world is turning a blind eye to the “weaponisation” of healthcare by armed forces in Syria, researchers warn.

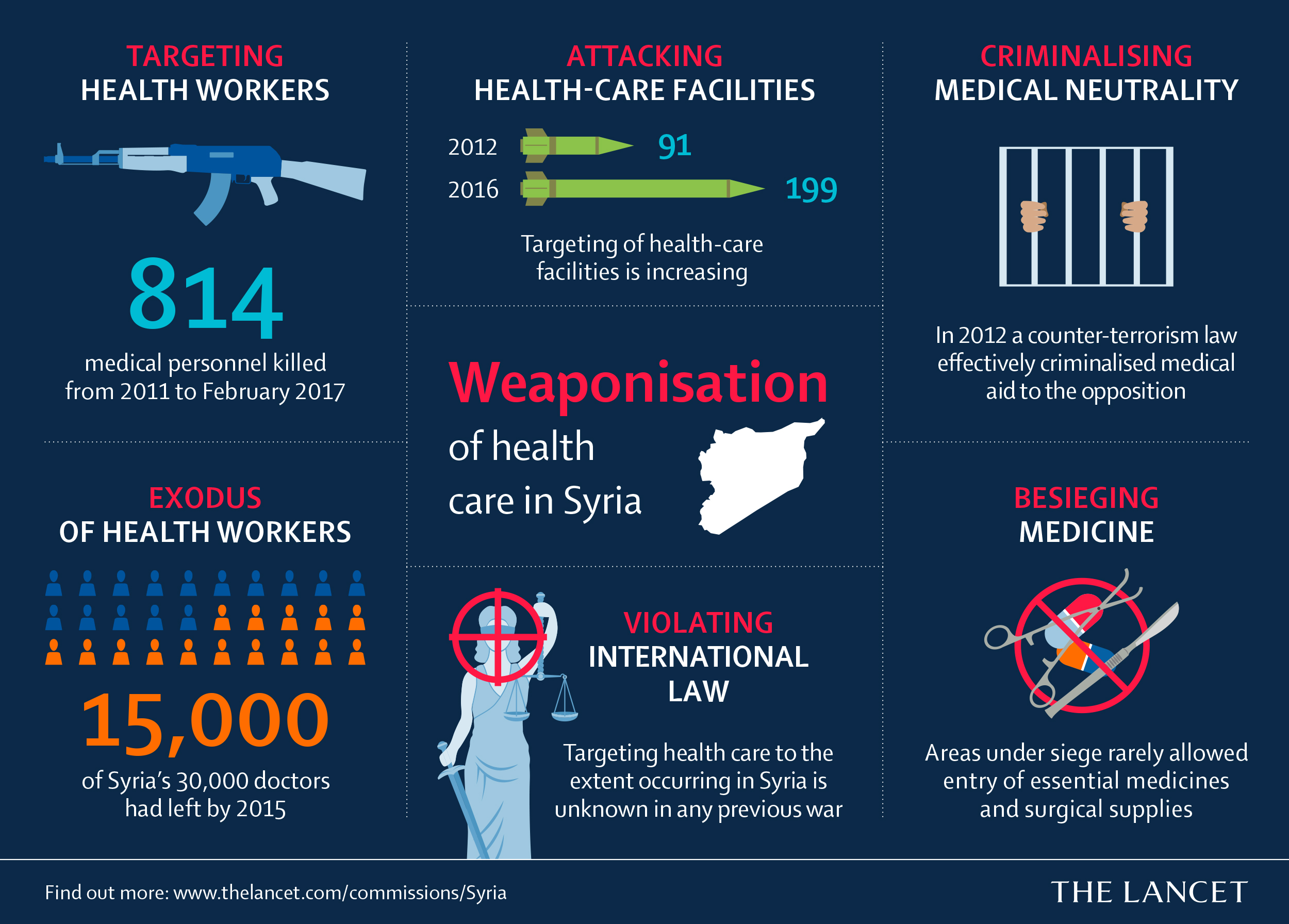

Health services have been targeted on an unprecedented scale during the six-year conflict, peaking at 199 attacks on health facilities last year, a report in The Lancet said.

The weaponisation of healthcare is a strategy of using people’s need for healthcare as a weapon by violently depriving them of it.

“The frequency and extent of targeting of health care [in Syria] is not known to have occurred in any previous wars,” the authors wrote.

The neutrality of health workers during armed conflict is enshrined in international law, including the Geneva Conventions.

Yet the Syrian government and allied forces routinely bombed hospitals and terrorised health workers as part of a violent military tactic, the authors, who are academics at the American University of Beirut, said.

More than 800 medical personnel have been killed during the conflict in Syria.

Around 15,000, or half, of Syria’s doctors have fled the country, leaving one doctor for every 7,000 residents in eastern Aleppo.

One underground hospital in eastern Aleppo was attacked 19 times before being forced to shut down. Another specialist health facility was bombed 33 times.

“The repeated bombing and shelling of medical facilities … is completely off-the-scale,” Fabio Forgione, a Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) project officer, told The Medical Republic.

MSF currently supports 23 health facilities in Aleppo, Idlib and Hama.

But maintaining a humanitarian response was “extremely challenging” when the lives of staff were continually put at risk, Mr Forgione said.

The decision to expand medical activities was a difficult one when structures were likely to be bombed as a strategy of war and medical personnel and patients killed as a result.

Underground hospitals and decentralised care have become more common in Syria.

But this “bunkerisation” ran contrary to the need for hospitals to be public, well-known institutions that were clearly marked as neutral zones, Mr Forgione said.

Using healthcare deprivation as a military tactic has left around 27% of Syrians with no access to health workers whatsoever.

In besieged cities, the Syrian government has stopped public-health measures such as water chlorination and most children born in Syria in the past five years have not been vaccinated for preventable diseases such as measles, rubella, tetanus or pneumonia.

The government rarely allows surgical supplies, dialysis kits or essential medicines into areas under siege. This has forced doctors to resort to unusual measures such as using urine bags with anticoagulants added for blood storage.

In clear violation of international humanitarian law, the government has criminalised the provision of healthcare to those injured by pro-government forces.

“The passing of this law was an effort to justify the arrests, detention, torture, and execution of health workers,” the authors wrote.

Few efforts had been made by the international community to hold to account those responsible for this persecution of health workers, the authors said.

The “unacceptable global indifference” to the plight of health workers in war zones must change through a framework of accountability and consequences, they said.

In July last year, the WHO began collecting data about attacks on healthcare workers and facilities in Syria, but did not include the perpetrators.

“[This] fosters a sense of impunity on the part of the Syrian and Russian governments, undermining the accountability needed to end these wars,” the authors wrote.

Efforts to refer Syria to the International Criminal Court have reached a stalemate in the UN Security Council.

Resolutions issued by the UN Security Council demanding humanitarian access have not been implemented due to diplomatic and political obstruction.

MSF called on the four out of five members of the UN Security Council involved in the conflict in Syria to do more to ensure that their forces respect international law.

The Lancet 2017, 14 March

Image credit: Photograph taken by Karam Almasri and supplied by MSF. The image depicts Dr Abu Wasim, a plastic surgeon, stands next to a damaged ward on the upper floors of a hospital in east Aleppo after it was hit by an airstrike in mid-October 2016. He is one of the seven surgeons left in East Aleppo.