There is a medical speciality for every personality archetype, as the yearly Battle of the Specialties shows.

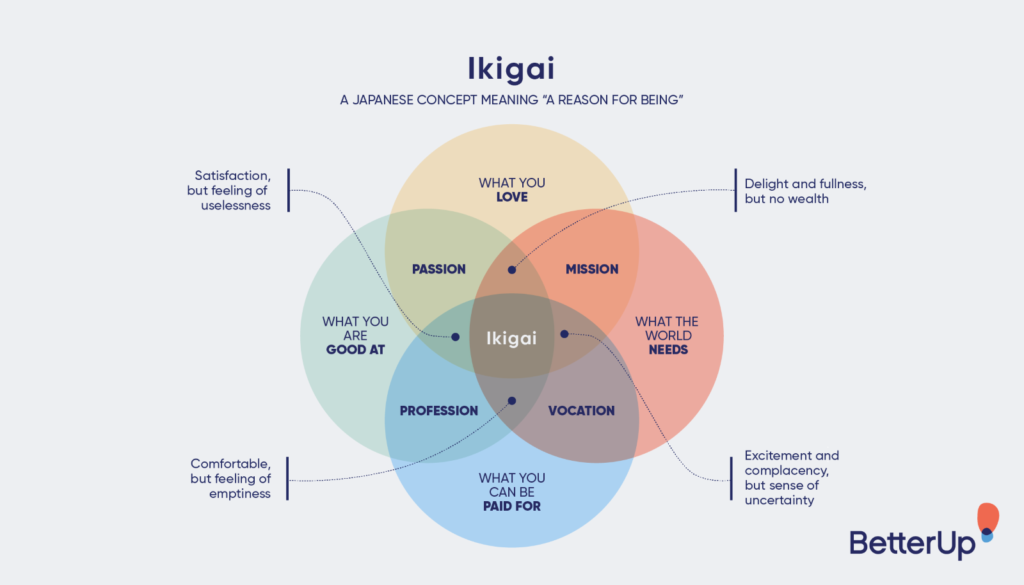

Professional identity is a vital part of a person’s overall identity.

The Japanese term Ikigai, literally “a reason for being”, places identity in general into context, emphasising its importance as a source of passion that gives value and joy to our lives. The benefits of a strong professional identity are substantial.

As a profession, medicine is a broad church. I have seen that breadth increase over the last 45 years. The democratisation of medical school entry within Australia, an explosion of new specialities and subspecialities plus mass immigration of international medical graduates have been drivers of the increased breadth. Thus, when medical schools admit “undifferentiated stem cells”, the first task of the graduant is to pick a tribe within the tribe.

Each year the Rural Training Hub in Bundaberg hosts a Battle of the Specialties. It’s a bit of fun, designed to engage medical students and interns with senior staff specialists championing and stoking robust conversations among the juniors about career options. As one of the old warhorses, it is interesting to hear my younger colleagues sell their specialty, both earnestly and playfully. During these times when the media is bursting with negative stories about the profession, it is consoling to hear these doctors speak so devotedly about their career paths.

We started with an oncologist, a neo-renaissance man and published fiction author. He quite honourably and with a tincture of mysticism spoke thus: While modern oncology has many treatment successes, there remains the daily humanistic challenges of talking about death and dying. He suggested that oncologists as a specialty serve as the high priests, since they are uniquely placed to embrace the grandeur of life as they are exquisitely aware that it is only death that so denotes it.

A prominent female general practitioner, with a side hustle as an amateur chorister, weighed in with the autonomy of being her own boss, running her own business, and having the flexibility of working as many or few hours as she wishes. The benefit of dealing with cradle to grave and beyond was mentioned (the beyond referring to the self-explanatory “cash for ash”).

A concrete thinking anaesthetist extolled the beauty of popping people off to sleep as the surgeon’s magical handmaiden in the hope that the number you put down equals the number you wake up. The bonus was that after the theatre show you could go home with no need for ongoing care.

A mid-career obstetrician gynaecologist became misty-eyed as she described the inexpressible joy of delivering a newborn. That, however, needed to be tempered with onerous on-call and even more onerous demands from midwives. Late-career gynaecologists can always go private and confine themselves to gynaecology!

The seasoned intensivist spoke of the sublime inner joy of having a nerdy alchemist understanding of fluid balance, electrolytes, organ function monitoring and higher order pharmacotherapy. In a moment of honesty, he did concede that it was really the nurses who did all the hard work.

The senior medical registrar doing general medicine waxed lyrical about the versatility of physicians, who are required to pick up all the odds and sods that the other specialties don’t want.

The orthopaedist put on a PowerPoint slide show, highlighting the great drills, screws, pins and plates that you can play with. Not to be outdone, the general surgeon showed a picture of the type of house and car you can afford because of doing surgery. This formidable woman added that as a person who makes a living from sewing, she had sewn the outfit that she was wearing and the matching tote bag.

I shall now state my own simple offerings, as an addiction physician, verbatim:

If you’re a concrete thinker, feel free to check your phone. If you relish abstract, then listen carefully.

There’s a mind-war that happens in many of us humans. It occurs in the subconscious. Some call it the Battle of Life. This is neuroscience at its most fascinating. The model goes like this: before you have a conscious mind, the wider environment is busy forming your unconscious mind. This unconscious mind has two parts; the autonomous you (I want to be me, I want to be in control) and the dependent you (I need you to feed me, to be kept warm and safe because I am defenceless). These two minds are pitted against each other. The consequences of this war are many and significant.

They include our ability to self-soothe in a healthy or unhealthy manner. This is an inward connection, a connection with Self. There is also an ability to connect with others in a healthy or unhealthy manner and get genuine satisfaction from that interhuman connection. Sometimes this includes a drive to be a people-pleaser. This is unhealthy and results in deep resentment. The alternative is having the courage to be disliked.

Sadly, the people-pleaser may have a drive to please those persons who were or continue to be perpetrators of unspeakable trauma. Sometimes the trauma was minor, but the wound was disproportionate due to high personal sensitivity.

“Addiction” in many cases is the symptom of that Battle of Life played out by incredibly courageous and resilient people. In the past a relationship with a particular substance or behaviour may have held some survival value. Over time it turned into self-sabotage. If you want to help them lift themselves up, then consider this speciality. You won’t be doing this on your own. In fact, you will need to build a multidisciplinary team around you. This is a real team sport.

When you tire of speed-dating problems that focus on bones, tissues, organs or organ systems and yearn to relate to real persons, with incredible personal stories over an ongoing period of years to decades, then consider this speciality. When you tire of treating disease and want to help people who have a disorder, but help in a genuine partnership, then consider this speciality. End.

At the evening’s conclusion, I was moved by the mixed sincerity and candour offered by my brothers and sisters in arms. Their words left me thinking that maybe we should all explore a second or third career for healthy professional vitality and longevity. They all sounded so great. All spokes of the medical wheel are necessary.

But more to the point, we all have complex professional identities. How wonderful it is to be able to counterbalance them with our complex and rewarding non-professional identities. That and our love of humanity. Without that balance of an identity beyond a profession, the spinning wheel will soon topple. A nice closing of the loop back to Ikigai.

Associate Professor Kees Nydam was at various times an emergency physician and ED director in Wollongong, Campbeltown and Bundaberg. He continues to work as a senior specialist in addiction medicine and to teach medical students attending the University of Queensland Rural Clinical School. He is also a poet and songwriter.