Injuries and infections are just the beginning of what doctors can expect after a cyclone – and you can expect them to get more intense.

If there is one thing I know, it’s cyclones. I grew up in Innisfail in Far North Queensland, where they were a regular occurrence. My youngest sister was born in one (Cyclone Justin) and my final year of high school was significantly affected by one (Cyclone Larry).

And let me tell you, you have to see it to believe it. Nature is a phenomenal force of which I am forever in awe.

Locals may love or loathe them, but irrespective of one’s feelings about cyclones, climate change is expected to make them more destructive, so they are of ever-increasing relevance to public health.

The literature on the health consequences of cyclones is hampered by the predominance of US-based research and a relative dearth of studies from Australia and the small, often developing, tropical nations where natural disasters result in a more serious impact. This is further compounded by study heterogeneity, exposure assessment bias, and limited follow-ups. Nonetheless, we know that cyclones are associated with numerous direct and indirect health effects and risks.

Overseas, cyclones are associated with an increased risk of all-cause hospitalisation for three months after the event and a consistently elevated risk of morbidity from injuries. This includes drowning from storm surges and injury from collapsing structures and moving debris.

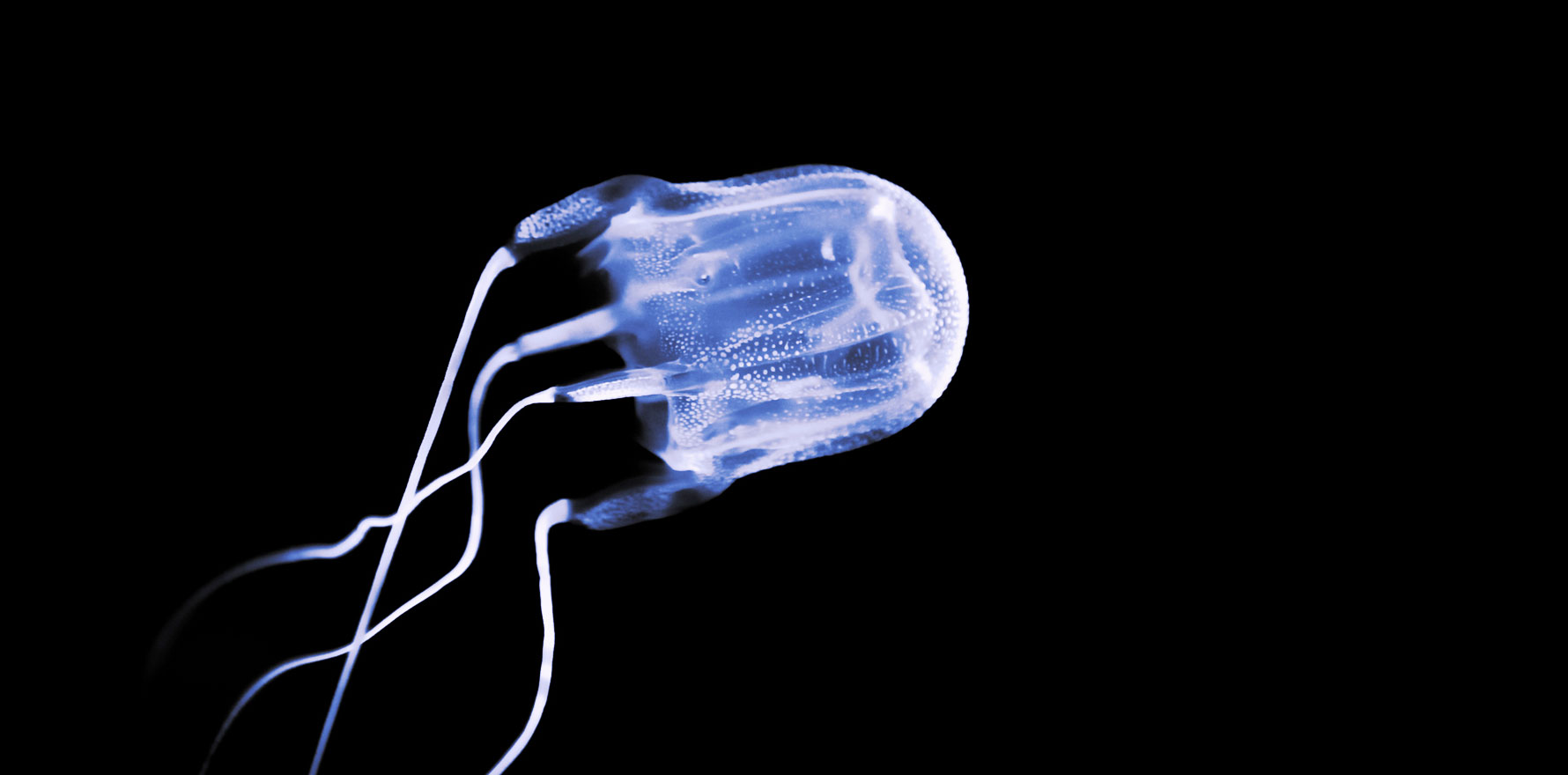

Infections pose a risk after cyclones, with increased morbidity rates from all infectious diseases found in international research. Contaminated floodwater and mud in Australia can carry an increased risk of wound infections, diarrhoea, conjunctivitis, and ENT infections, as well as unique tropical infections such as melioidosis.

A recent melioidosis death in Cairns prompted calls for caution after Cyclone Kirrily. Melioidosis, caused by a bacterium found in soil and water across Northern Australia, is a particular risk during the wet season, where heavy rains bring the bacteria to the soil surface.

The heavy rainfall and flooding associated with cyclones provide the perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes, which can cause mosquito-borne infections such as Ross River Fever and Barmah Forest Virus. In Far North Queensland, dengue fever is also a risk, where outbreaks can occur annually.

The relationship between cyclones and obstetric outcomes is an interesting area. A 2022 study that analysed adverse birth outcomes in Queensland found an association between exposure to environmental stressors in early to mid-pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. It found that cyclone exposure in early pregnancy was associated with significantly higher odds of preterm births, while mid-pregnancy exposure was associated with higher odds of low birth weight.

The study noted the limited Australian research into perinatal outcomes and tropical cyclones, despite the relevance and importance of the issue.

Analysis of data in East Asian countries found a significant association between cyclone exposure and respiratory disease mortality in the over-65 age group. This is consistent with American research, which has suggested increased morbidity of all respiratory diseases following a cyclone.

The reasons for these findings are unclear but may be due to a combination of factors including high wind speeds, sudden decreases in atmospheric pressure, the dissemination of bacteria and allergens (such as mould), and increased air pollutants during debris cleaning.

Cyclones can cause disruptions in hospital care (Cyclone Yasi resulted in the pre-emptive evacuation of both hospitals in Cairns, the largest evacuation of a hospital in Australia). The infrastructure damage that can result from cyclones interrupts healthcare delivery. Power outages and flooding can further limit access to health services.

Power outages are also associated with the health risks of food poisoning from contamination, potentially compromised medications, and the risk of asphyxiation from generator use (this was responsible for a death during Yasi). Furthermore, power outages can cause problems for those who use medical equipment that is electricity dependent. Outages after cyclones can last for weeks.

Mental health issues are a known consequence of any natural disaster. In international research, cyclones are associated with a higher mental illness prevalence for up to three years after the event, an increase in mental health service visits, and consistently higher rates of PTSD.

Cyclone Larry, a severe cyclone that decimated the small North Queensland town of Innisfail in 2006 (and at the time the most powerful cyclone to hit Queensland in almost a century), was found in one study to cause moderate to severe PTSD symptoms in approximately one in five primary school children and one in twelve secondary school children 18 months after the event.

An Australian study that assessed NSW residents who experienced flooding after 2017’s Cyclone Debbie found a significant association between those whose lives were directly or indirectly affected by the flooding and PTSD, as well as a strong association between loss of access to healthcare and every mental health outcome investigated.

GPs are at the coalface of the Australian health system, are the cornerstone of successful primary healthcare, and are integral to disaster response. It is self-evident that we should be included in the disaster planning process and be thoroughly supported in providing care to our communities after cyclones and other disasters.

The AMA’s position statement on the involvement of GPs in disaster and emergency planning calls on all levels of government to give consideration to the numerous important roles that GPs can and do play in emergency and disaster situations.

The RACGP has several resources in this area, such as its Summer Planning Toolkit, resources in managing emergencies in general practice, and information for GPs in disaster-affected areas. The college offers an online CPD activity, Disaster recovery – providing psychological support, as well as a Disaster Medicine Specific Interest Group. Your local HealthPathways may also have pathways with localised links for post-disaster healthcare. Lastly, the Australian Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub is a government platform with numerous resources on disaster preparation and response.

Related

Regarding the provision of mental healthcare after cyclones, the RACGP has a fact sheet on mental health care in emergencies and disaster, and the Australian Psychological Society has information on psychological support after disasters. The World Health Organisation and the Red Cross also have excellent guides on psychological first aid. Phoenix Australia has produced guidelines on the prevention and treatment of acute stress disorder and PTSD in the context of disasters.

Of course, GPs must also look after themselves and their own mental health during these events, and practise self-care as much as possible.

More research is required on the many facets of the cyclone-health relationship, particularly in Australia and the vulnerable Pacific nations that are most at risk of the impacts. Improvements are clearly needed in the Australian disaster response space, with each new natural disaster often exposing deficiencies across all sectors and levels of government.

Finally, GPs should be better recognised as the specialists we are in the provision of post-disaster primary healthcare, and fully integrated into disaster planning and response frameworks.

Dr Brooke Ah Shay is a GP in the Northern Territory; formerly working in Arnhem Land, she is now completing her Masters of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in Darwin.