Mitigate the acute infection and reduce the risk of lingering symptoms, says an Australian expert.

Some simple steps can help mitigate long covid and treat its symptoms, according to the head of the long covid clinic at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney.

With 750 million covid survivors globally, more awareness of the treatable traits would help address this public health problem, respiratory physician Associate Professor Anthony Byrne told delegates at the Immunisation Coalition ASM in Melbourne last month.

GPs played an important role at every stage in the long covid journey, from identifying high risk patients to diagnosing long covid and treating it and comorbid conditions, Professor Byrne said.

How to diagnose long covid?

The first step in combating this public health problem was diagnosing and mitigating the infection when it occurred, said Professor Byrne, whose multidisciplinary long covid clinic was one of the first and has seen over 1000 patients in its three years.

“When that patient calls you and says they’re covid-positive, have a think about giving them treatments that might reduce the chance of them getting long covid, rather than waiting for three months for them to tell you that they’re still sick,” he told TMR.

One barrier to diagnosing long covid was that patients and clinicians alike often didn’t think of linking a prior infection to current symptoms.

He recommended PCR tests to confirm the covid diagnosis, and said he gave patients with chronic illnesses PCR request forms in advance to prevent diagnostic delays.

Some data suggests antivirals such as nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid, Pfizer) cut long covid rates by a quarter compared to no treatment.

Metformin also appears to help. Among patients who took the drug for two weeks at the time of diagnosis, 6.3% had long covid a year later compared to 10.4% of those who didn’t take metformin.

Similarly, inhaled steroids with budesonide reduced the risk of long covid while also treating symptoms in the acute phase of the illness, such as cough, Professor Byrne told the meeting.

One challenge in diagnosing long covid was that there were more than 200 symptoms described in this population, he said. But the simple definition is the presence of these symptoms at least three months after infection that is not otherwise explained.

The most common symptom, by far, is fatigue. But mild cognitive impairment (brain fog), breathlessness (with or without cough), pain (including chest pain) and mental health problems (with or without sleep disturbances) are frequent complaints.

“Although there’s not one biomarker or one test, the diagnosis of long covid should not be hard. It involves taking a history, knowing the patient, knowing what they were like before and what they’re like now. That’s what GPs do all the time, particularly if they’ve got regular patients,” he told TMR.

Another challenge is that many patients were complex, with one or multiple comorbidities.

This complexity played a role in patients not getting diagnosed and sometimes being dismissed by healthcare professionals, Professor Byrne said.

But of the patients Professor Byrne and colleagues saw in their clinic, “99% of them who think they have long covid have long covid”.

“So the diagnosis is not in question. What’s in question is how much blame, if you like, to allocate to long covid, and how much to allocate to their poorly controlled diabetes or their chronic pain syndrome or their sleep apnoea that’s undiagnosed, etc, etc.”

Who’s at high risk of long covid?

Mitigation strategies such as metformin or inhaled corticosteroids were particularly important in patients at a high risk of long covid, such as those who were un- or undervaccinated, had severe acute covid infection (which included hospitalised patients or those with more than five symptoms), were older, female or who had comorbidities (such as hypertension, diabetes, or who were immune suppressed or had autoimmune disease).

More surprising risk factors included stress at the time of infection and low self-esteem. Professor Byrne has also seen a high number of patients with ADHD.

Doctors can also use a new long covid risk calculator, CoRiCal, which can be found on the Immunisation Coalition website.

How to treat long covid

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 can cause sweeping changes to the body.

“We see, in the severe spectrum, lung alveolar injury and diffuse alveolar damage on autopsy. SARS-CoV-2destroys type II pneumocytes and causes inflammation, and then you have this cytokine storm and viral replication,” Professor Byrne said.

“Within the vascular system, we see thrombosis, and we see dysfunction and damage on the alveolar level and coagulopathies. Then within the airways, we see problems with inflammation and problems of dysfunction within the airways.”

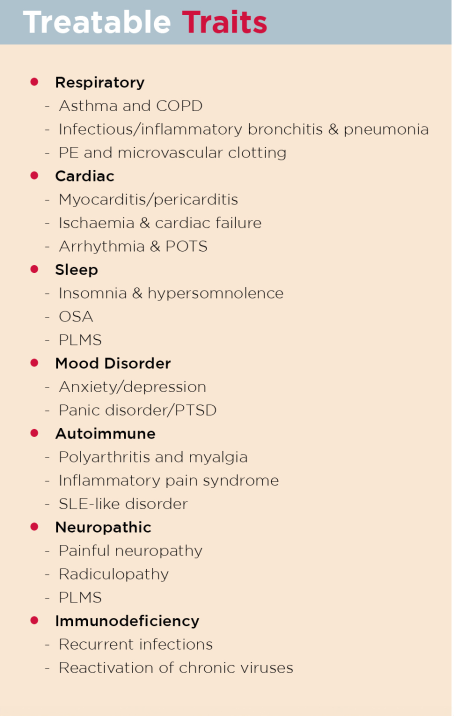

The good news was that GPs could address “treatable traits” in long covid individually, Professor Byrne said.

“It’s helpful to compartmentalise the condition,” he said.

“So, have an approach to fatigue … Look at their sleep hygiene, do some simple tests for thyroid, iron, diabetes, think about mental health, think about confidence and think about things that you can act on and treat.”

Professor Byrne said he would evaluate conditions in order of life-threatening, important and then annoying and disabling causes.

For example, long covid patients had a high risk of cardiovascular events: “That chest pain could be cardiac – it probably isn’t – but you’ve got to do the usual things and make sure that it’s not a heart attack, that it’s not unstable angina, and that it’s not a pulmonary embolism,” he said.

Patients will often have already presented to hospital or other specialists, so test results may already be available.

“They’ll turn up to an emergency department for chest pain and the ED doctors will do an ECG, troponin [test] and chest X-ray, they’ll be fine, and [doctors] will send them on their way, but they have still got chest pain, scratching their heads and thinking ‘Okay, well, that’s good. I’m not dying, apparently, but I’ve still got terrible chest pain that I’m worried about’.”

It was also helpful to consider the lungs and not just the heart when a patient complained of breathlessness, Professor Byrne said, noting the lack of spirometers compared to ECGs in many GP surgeries.

“In evaluating breathlessness … we do identify lots of our patients that have subsegmental mismatch defects on V/Q scanning that are not found on CT pulmonary angiography, and we see these patients get better with anticoagulating them, as you would expect.

“We see a lot of myocarditis and pericarditis when it’s looked for, and we also see a lot of anxiety and panic disorder, and the interplay with that and small airway dysfunction, asthma, dysfunctional breathing.

“The chest pain is really interesting. Sometimes it can be because of pathology, such as PE – often it’s not – and we see pleuritis, and we see a neuropathic-type syndrome in these patients, with presumably nerve injury as the potential cause of their pain.”

Patients with long covid often had normal lung function when tested, but there were some with evidence of small airway dysfunction when oscillometry was used, Professor Byrne said. Those patients, according to early data from their clinic, tended to improve over six months when put on inhaled steroids.

But it was important to remember that this was a respiratory virus, he told TMR.

“It does cause recrudescence and new onset asthma … And occasionally there’s infected bronchitis and pulmonary embolism.

“Sometimes you can get this organising pneumonia that needs steroids to treat in the post-acute period of time,” he told the Melbourne audience. Patients were at an increased risk of bacterial, fungal and other infections in the acute and post-acute phase.

“Venous thromboembolic disease is also seen in the acute phase, but we commonly see this in our long covid population.”

There are resources for long covid on the Australian Lung Foundation website, and St Vincent’s Hospital offers an online program for mental health anxiety and depression which patients can take.

Long covid patients often had comorbidities, such as diabetes, sleep apnoea, ADHD, rheumatoid arthritis and COPD, and the infection often worsened these conditions. Managing and trying to improve these chronic conditions was an important job for GPs, Professor Byrne said. There was some data to suggest that long covid patients often improved after 24 months, but Professor Byrne said he still saw patients who were persistently unwell beyond that.

“It results in airway, vascular and nerve injury, organ dysfunction, and it leads to reduced quality of life. And those symptoms have real impacts on social functioning and economic and professional roles in these patients.”

For patients at the St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney clinic, at least one in three can’t work or are working in impaired capacity at least six months after their infection. Many have seen multiple other specialists, which is costly and difficult, and are “very debilitated”, he said.

In general, data suggests that long covid patients frequently present to doctors, which was an important distinction to the long-term consequences of influenza infection, he said.

Ultimately, keeping long covid in mind and treating it seriously at the time of infection would improve the situation for individuals and the public health consequences of long covid downstream.

“Many patients that I see two or three months later that actually were PBS eligible for antivirals did not get them because their prescriber or GP thought that they were fine, and they were at low risk of needing hospitalisation.”

Professor Byrne said clinicians should keep a close eye on eligibility criteria for metformin and Paxlovid in the acute setting as it was frequently updated.

Patients were eligible for Paxlovid if they had been previously hospitalised for covid, and private script was always an option for this and metformin , he said.

“There’s probably some reducing efficacy over time, and in some patients – and there is data to support this – remdesivir intravenously is probably better.

“If there’s the capacity and the willingness to use that for a high-risk patient, I would have a lower threshold for bringing a patient in, giving them three days of IV remdesivir, even if they don’t have hypoxic respiratory failure if they’re at a high risk of long covid for other comorbid condition reasons.”

Stigma still surrounds this condition, and people often aren’t listened to by the medical professionals they see, Professor Byrne said.

“The message is: don’t just throw up your hands. It’s important to believe patients.”