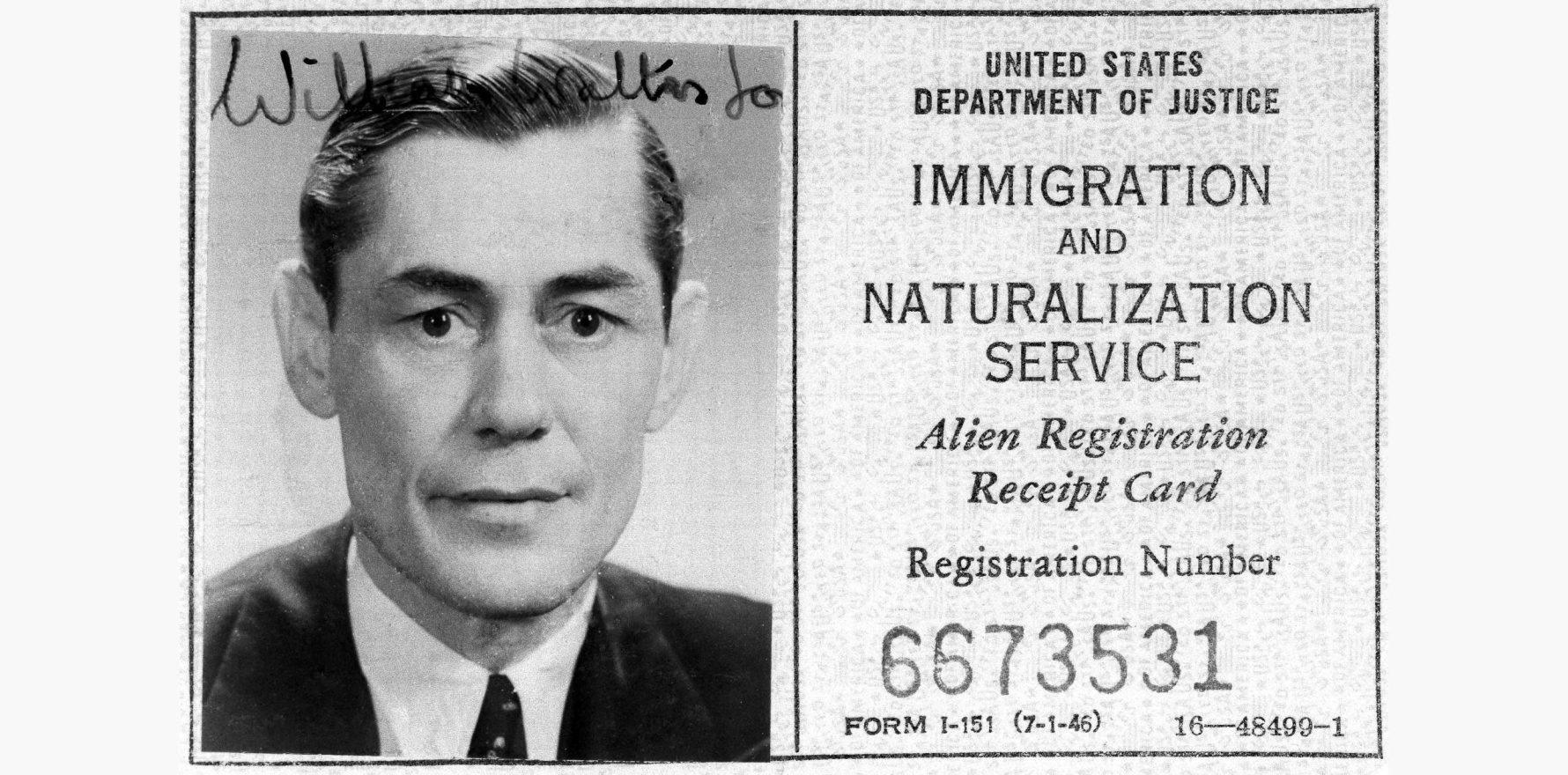

Would you trust your mental health to this man? Plenty did. Picture: US Department of Justice.

More than any other discipline in medicine, psychiatry attracts flamboyant, eccentric or charismatic characters; and in that phalanx William Sargant stood out.

He was deeply controversial within the profession, had equally divisive opinions among those whom he had treated and, through his books and talks, had the reputation as a great man of his profession who improved the image of psychiatry.

He was a dominating and charismatic character such as does occur in medicine and often obtained cures through sheer force of character, although they did not necessarily last. That was the image during his lifetime; time, as it often does, has led to negative views of his work and personality.

Sargant represented an arm of a division in psychiatry that emanated from the Maudsley Hospital. Aubrey Lewis, cautious about adopting new treatments, especially physical, was a pioneer in social psychiatry and had a highly critical intellect.

Eliot Slater and Sargant were focused on treatment of the patient at a time when there were few options, dismissive (if not hostile) to psychoanalysis and psychotherapy and prepared to try anything that could relieve symptoms. The Maudsley could not contain the tension and they went their own ways, Slater to Queen’s Square and Sargant to St Thomas’ Hospital. Their book An Introduction to Physical Methods of Treatment In Psychiatry had multiple reprints.

They made an interesting combination. Slater, who had an intellect that easily matched that of Lewis, eschewed Sargant’s avid self-promotion, wrote superb articles on a range of subjects and was not associated with treatment abuse.

Sargant, who came from a Methodist background, had an uncompromising and evangelical approach. His dogma was that psychiatric illness arose from brain disease and required physical treatment. He had no shortage of glowing testimonials from those that he helped; the failures were ignored, kept in the background or only emerged later.

The physical or biological treatments started in the 1930a, with deep sleep therapy (DST) a little earlier. DST, started by Scottish psychiatrist Neil Macleod with bromides, was popularised by Swiss psychiatrist Jacob Klaesi using barbiturates with schizophrenics. The therapeutic rationale was that by “switching off” the brain, distressed thoughts and emotions would be removed. Questions were raised about its safety from the start but it was used widely for all kinds of conditions. There was never a consensus about its application. In their sleeping state patients required intense care, not far removed from that used in ICU.

Yet the hazards of physical treatments did not deter practitioners from its use. Private psychiatrists would offer it to middle-class patients needing a break from “stress”, a useful money spinner. In Melbourne a clinic associated with the psychiatrist Reg Ellery had a “sleep temple”. In South Africa, until well into the 1990s, private patients could go to a clinic for “a nice sleep” aided by large doses of Valium. The singer Mario Lanza died during “twilight sleep” to lose weight.

In the late 1940s, looking at the treatments and disillusioned with psychoanalysis, Humphry Osmond went to faraway Weyburn in Canada and did the world’s largest trials of LSD. Ronnie Laing was horrified by physical treatments, trained in psychoanalysis and proceeded to develop his anti-psychiatry rhetoric, blaming the bourgeous family for mental problems.

Convulsive therapy, induced by camphor, or ECT as it became, produced remarkable results with depression and often with schizophrenia, although this did not last. Manfred Sakel’s insulin coma therapy (ICT), dangerous as it was, was claimed by some to produce cures in up to 40% of cases – this was unheard of in psychiatry at the time and quite remarkable.

The historiography shows that ICT was discredited by the studies of Bourke and Ackner in the 1970s. The late Max Fink did a controlled study of ICT in 1968 showing that it was as effective as haloperidol but clearly not as convenient or easy to apply. He maintained that with modern technology it still had a place in treating intractable cases.

Finally, there was psychosurgery, known then as lobotomy, the severing of frontal lobe white matter. In retrospect, it was beyond frightening: the insertion of a probe that was waggled around to sever the nerves with little discretion. Some patients did improve; others were considered cured because they were left with inert and passive personalities. This was a world away from the modified stereotactic leucotomy that is still done today in highly selected cases (mostly OCD) with the extirpation of no more than 2 millimetres of tissue.

It is important to remember that up to that point psychiatry had no treatments for the severe conditions in their patients, only sedation, such as paraldehyde or barbiturates, or ineffective efforts such as water immersion. Malariotherapy only worked for advanced cases of neurosyphilis.

For psychiatrists, who had done no more than custodial care, for the first time they could return to their medical roots, treating patients with positive results. This not only led to an improvement in the collective professional esteem, participation of patients in discussions about the treatment was a start to levelling the doctor-patient imbalance.

Sargant took to physical treatment without restraint. When the Second World War came, he added in chemical abreaction for combat neurosis. He unceasingly promoted the treatments and was unrelenting in their application. Herein lay the danger.

Related

Regardless of a high rate of complications Sargant would plough on until he got a result that satisfied him. If he did not, he blamed the patient’s personality, not his treatment.

Although he was not a great writer, his books – such as The Battle for the Mind, A physiology of conversion and brainwashing (written with Robert Graves) had great public appeal and promoted the belief that treatment was far more straightforward than it was in practice.

What Sargant is most remembered for was his use of DST, which he took to extremes, often keeping patients in a semi-comatose state for several months. While comatose he would give them repeated bouts of ICT and unmodified ECT. When all else failed, psychosurgery followed.

Nursing staff had to wake patients for toileting and feeding before they went back to sleep. Having impaired consciousness for long periods could lead to any number of problems, notably thrombosis, emboli, heart attacks, strokes and pneumonia.

Ann Dally, a critic, noted that despite the complications and coercive aspects of DST, he got away without any deaths, possibly a reflection of the good nursing care.

And no one put DST to such extensive use as Sargant and his Australian epigone, Harry Bailey. The Chelmsford nursing home where Bailey’s patients were treated has entered into the legends of horror with multiple deaths that were covered up or ignored until a Royal Commission in 1988 led to DST being banned.

When Bailey was being pursued by court cases, Sargant was asked to give evidence to support him but refused. By then he was aware that the game was up and he could not support Bailey, who took his own life when his defence insurance was withdrawn.

There has been no shortage of writing about Sargant. While his reputation has rather shrunk under the criticism over time, there are positive reports on him.

He was described by Desmond Kelly as the most important figure in post-war psychiatry – a category that Ronnie Laing may have disputed – and the most outstanding clinician and teacher of his generation.

Substantial figures among his trainees included David Owen, later Foreign Secretary and Minister for Health; Jim Birley, president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, and Peter Gautier-Smith, later dean of The National Hospital, Queen Square. All were unstinting in their praise of Sargant and this cannot be swept aside.

The latest addition to the Sargant literature is The Sleep Room: A Sadistic Psychiatrist and the Women Who Survived Him, by Jon Stock. The book focuses on casualties of Sargant’s DST, including actors and models. Sargant is portrayed as a charming monster who could not be swayed and refused to accept there was anything wrong in his treatment.

Sargant provides all the material for a sensational story. Good looking and physically imposing (he had been a champion rugby player and this got him into St Mary’s medical school), rumours swirled about him sexually abusing patients and being into “swinging” despite an apparently close marriage. He wildly promoted the use of psychedelics. He had US connections and was widely believed to have joined Donald Cameron and others in unethical CIA experiments.

There can be no doubt that Sargant deserved to be deregistered but he operated at a time when doctors could get away with far more, patients were reluctant to challenge their exalted position and old school tie connections also made a difference.

A quote from Desmond Kelly is worth repeating:

“He was a rebel with a cause… His work at St Thomas’s Hospital was legendary. When he was physician in charge of the department of psychological medicine, more medical students entered psychiatry than from any other medical school. He had massive self-confidence, sometimes amounting to recklessness, therapeutic fervour, stubborn persistence and clinical intuition. It was this last quality that was the most remarkable. He had an amazing sixth sense – a talent for taking short cuts to knowledge. So many of his former patients have said ‘Dr Sargant saved my life’. A rare statement in the case of other psychiatrists, but a commonplace with Will. Most of all, he gave his patients hope.”

This assessment cannot be separated from his otherwise calumny. Sargant went to extremes regardless of the consequences, behaved badly in some circumstances and engaged in questionable practices; nevertheless, he was an important figure in psychiatry, notably with his treatment of war neurosis.

Having dealt with the sensational and abusive aspects of the story, what do we have left?

William Sargant joins the ranks of charismatic doctors who have been present since the start of the profession. Some outstanding examples are Leander Starr Jameson, Hamilton Bailey, Bernard Spilsbury, Christian Barnard and Jacques Lacan.

In each we see the same progression. A brilliant and talented physician is seen as getting great results where others fail. They obtain a reputation as being nothing short of magical in their ability before the inevitable rule on charisma sweeps in: they have to keep delivering the magic or lose the followers. This results in treatment extremes where the failures are overlooked and the casualties rise.

William Sargant is a case study in the dangers of a charismatic doctor. In all his follies and successes there is much to learn about the practice of medicine. Hubris is always followed by Nemesis.

Robert M Kaplan is a forensic psychiatrist, writer and historian.