Hitting that button is regarded as one of sleep’s original sins, but a new study finds snoozers raring to go on cognitive tests.

Your faithful Back Page correspondent has confessed in a prior story to being of an evening chronotype, aka Not A Morning Person.

We may as well go further and confess to regularly hitting the snooze button for a precious extra 10 minutes of being asleep at a time when our body actually wants to be asleep.

We say “confess” because, as previously noted, this behaviour incurs a hefty moral stigma from those who spring out of bed at dawn to begin their wholesome day.

Just Google “snooze button” and look at the headlines:

Stop Hitting Snooze! Here Are 8 Expert Tips for Waking Up on Time

The Negative Impact of Hitting the Snooze Button

Snoozing Your Alarm Is Bad for You. Here’s What to Know

How to Stop Hitting the Snooze Button: Follow These 14 Tips to Never Hit it Again

This Is What Happens To Your Body When You Keep Hitting Snooze

The results in that last one are, in case you were wondering, “alarming”.

Luckily we can go on ignoring all those stories and whatever riff-raff science informs them, because now there’s this paper in the Journal of Sleep Research.

The team performed two studies, one to investigate the characteristics of people who snooze and why they do it, the second to analyse “the acute effects of snoozing on sleep architecture, sleepiness, cognitive ability, mood, and CAR [cortisol awakening response]”.

Since cortisol takes about 35-40 minutes after waking to shoot up and increase your alertness, they reason, waking and then snoozing through that period may actually make you feel less sleepy and have better executive functioning as soon as you get up.

This is a counter-hypothesis to the concerns about fractured and shortened sleep (shortened because you should just set your alarm to the time you plan on getting up instead of factoring in a snooze).

More than 1700 people, mostly Swedish, responded to a survey about sleep and waking habits, around 70% of whom copped to using the snooze function at least “sometimes”. The mean snooze duration was 22 minutes, but this included at least one result of 180 minutes … which we think stretches the definition of snoozing.

Snoozers were younger and four times more likely to be evening chronotypes than the non-snoozers. There was no difference in reported sleep quality, though the snoozers were three times as likely to report mental drowsiness on waking.

Most common reasons given: “feeling too tired to wake up” (25%), “it feels good” (17%) and wanting “to wake up more slowly/softly” (17%).

The second study was small but perfectly formed with just 31 participants, all habitual snoozers, with a range of sleep and other health problems excluded. (“We did not perform a power analysis; the sample size was determined by resource limitations.” That’s one way to do it.)

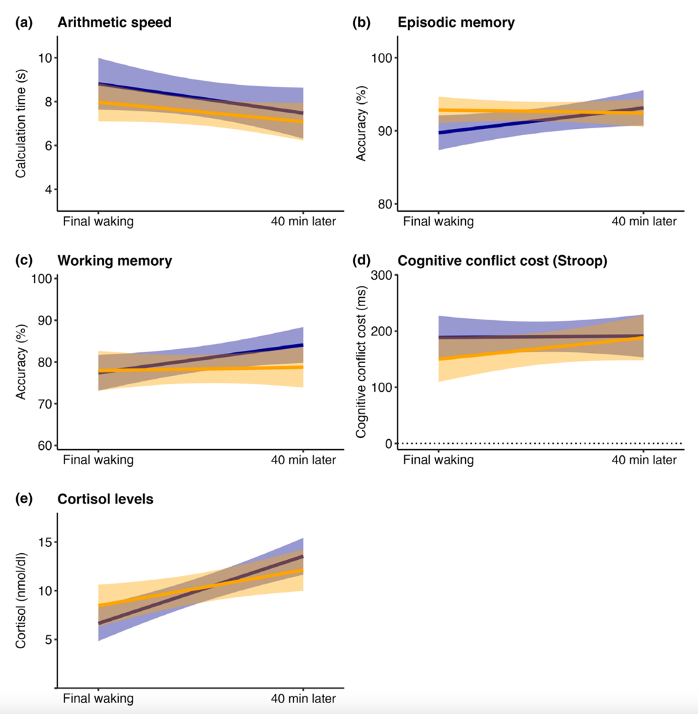

They all spent three non-consecutive nights in a polysomnography lab – one night for practice, one with snoozing (30 minutes total, three snoozes) and one without. In the morning they gave a spit sample (to measure the cortisol awakening response), underwent sessions of cognitive testing for processing speed, episodic memory, executive functioning and the Stroop test for colour-word congruence – including one session immediately on waking and one after 40 minutes.

They were quizzed on their sleepiness, effort, performance and mood.

Performance in all tests except Stroop improved with time awake in both condition, showing a “sleep inertia” effect – but this effect was less in the snooze condition. By the 40-minute mark the non-snoozers had caught up.

Cortisol was higher in the snooze condition at waking, but the gap had closed by 40 minutes.

Somnography showed that snoozers never got up straight from slow-wave sleep – which may increase the effects of sleep inertia – whereas some sleep-throughers did.

Visually, you can see that the non-snoozing makes for a steeper curve (except on Stroop, and arithmetic speed, which bizarrely seems to decrease in both conditions):

On most other factors there was no significant effect. The authors were surprised to report that snoozing did not affect self-reported sleepiness or mood.

“Although one could argue that the snooze period would be better spent sleeping, considering the detrimental effects of reduced and fragmented sleep, snoozing appears to serve a function for those who engage in this behaviour,” write the authors, sounding somewhat bewildered and still a tad disapproving.

Although more study is needed to confirm that people perform better on cognitive tests after snoozing, “it is at least clear that snoozing does not lead to cognitive impairments upon waking in habitual snoozers”.

“While snoozing did not clearly affect subjective sleepiness or mood,” they conclude, “it may be beneficial in relieving sleep inertia and improve cognitive functioning right upon waking.”

The Back Page is taking that as a very rare vindication for our sleeping and waking habits.

Send lullabies to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.