There’s a special place in the swamp for us lady GPs who find ourselves caring for the complicated, vulnerable patients no one else wants.

In our previous articles, we’ve talked about how the swamp works. I wanted to spend some time talking about what the swamp is like. Especially for “lady doctors”.

I am a “lady doctor”. This is not a term I choose, it is chosen for me. Internationally, and across professions from oncology to dentistry, “lady doctors” are seen to be kinder, more compassionate, more willing to provide cut price services for the needy, and more able to understand mental health and complex care. In other words, we carry the legacy of Florence Nightingale and Sister Kenny without their spicy attitude towards the patriarchal establishment.

Before my equally capable and competent male colleagues feel besieged, I don’t think this is true, rational or justified. But discriminatory attitudes rarely are.

Often these gendered expectations are unconscious.

“I see Doctor Mathew, Mark, Luke or John for simple things” patients say, “but when it’s complicated, I always come to you.”

This would be the compliment it was meant to be if there were no structural sexism in the health system. Unfortunately, Messrs Mathew, Mark, Luke and John attract around $6 of Medicare money per minute of their six-minute medicine, while my patients are subsidised about $1.20 for theirs. Which means $50 take-home before tax for me for an hour of complex mental health or antenatal care.

No wonder we all find the “greedy doctor in the new Mercedes” narrative so galling. No wonder there is a 24% gender pay gap in general practice.

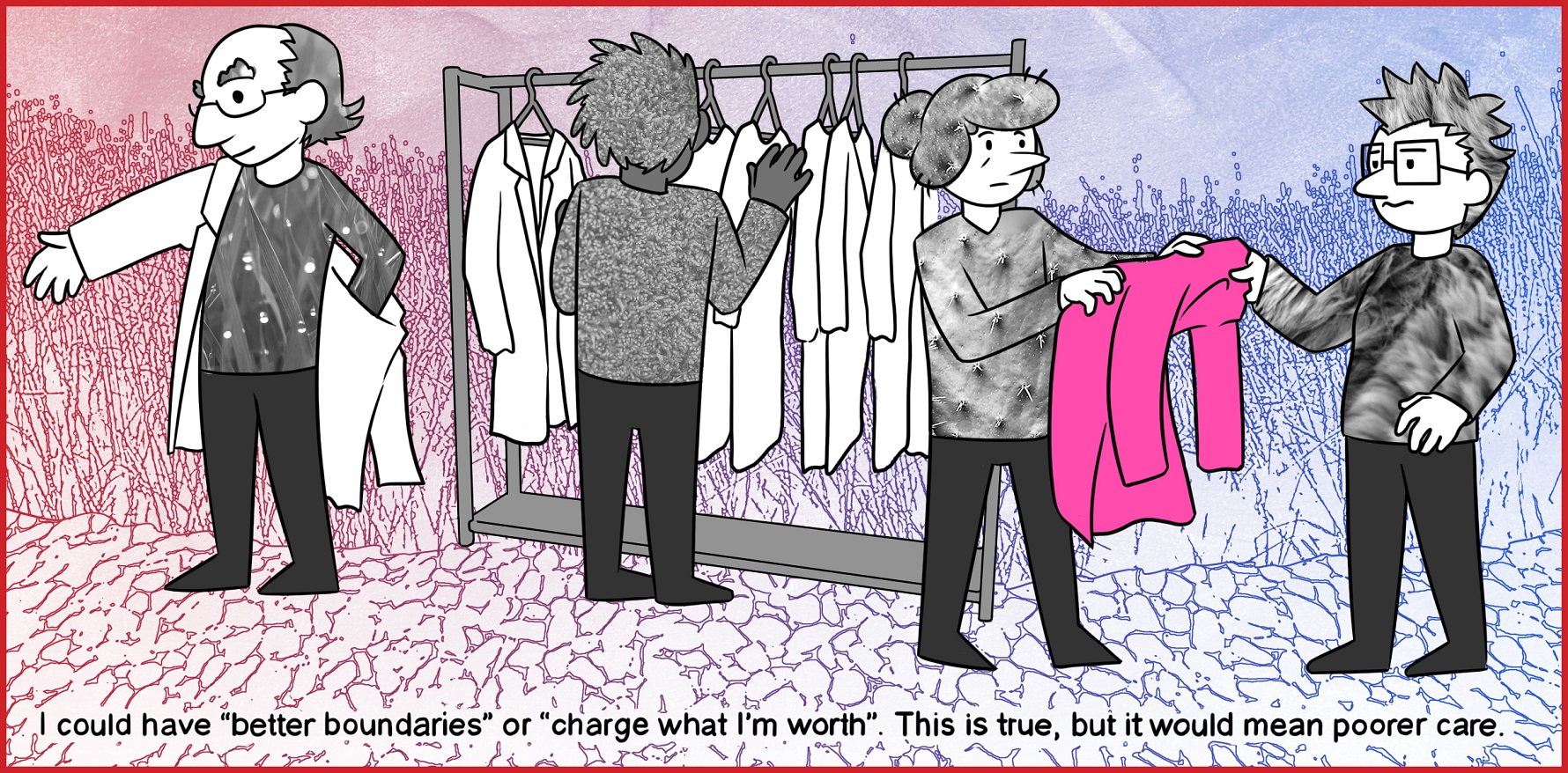

Of course, one could argue that the problem lies in my control. I could have “better boundaries” or “charge what I’m worth”.

This is true, but it would mean poorer care. Interestingly we never say a hip replacement would be quicker if the orthopaedic surgeon had “better boundaries”, we let him take the time he needs.

We also never discuss what would happen to the poorest, most vulnerable patients in the system if all GPs “charged what they are worth” across the system. When young female GPs approach me and tell me they’re failing because they can’t manage their billings, I usually tell them “you don’t have a time management problem, you have a complexity allocation problem”. Partly it’s the patients, but partly it’s the receptionist who unconsciously sees a person quietly disintegrating, or sobbing with a few unruly kids in tow and decides the lady doctor is a perfect fit.

So let’s walk though a typical day in the pink swamp, for me and a number of my colleagues.

Patient 1 has early dementia, and comes to see me with her long-suffering daughter. The 40-minute consultation is punctuated by resentment from the patient, who, despite her daughter’s best efforts, feels her rights to consent are being eroded. In fact, her memory of being consulted is eroding much more rapidly.

My patient doesn’t understand why her licence has been taken away. She doesn’t understand why all these strange carers are coming to her home. She resents this talk of respite. And in the fragments of conversation her daughter and I can exchange between her repeated and quite justified requests for explanations, I manage to get a list of this week’s paperwork – the disability permit for her daughter’s car; yet more NDIS paperwork; the form to reassure the exercise physiologist that she is fit to exercise, which I thought the exercise physiologist was trained to assess; and the endless referral letters.

In between all that, I arrange a time to see her daughter separately. She looks exhausted.

The next five patients are survivors of trauma. Over and over I hear stories that stay with me, and add to the festering heap of vicarious sludge that has built up in the back of my brain and heart. Nobody would believe some of this. It is more horrible than anything a novelist or screenwriter would consider. And in my day, it goes on, and on, and on. It is unending, unfixable and at times deeply unbearable.

One of these patients is a doctor, who not only survived personal trauma, but has been systematically exploited and abused by the hospital system. She has just been disciplined by her supervisor for her “time management skills”. In the last month, she has been covering for three colleagues who are off on “stress leave” which means she was supposed to be in two theatres and an admission clinic simultaneously. Unsurprisingly, she was late for two of them. She cannot take time off, because she has already had too much time off training (according to her college) due to maternity leave and personal health issues. She has panic attacks just walking in the door of her hospital.

Like 33% of her colleagues, she has also survived persistent sexual harassment as a junior doctor. I write an unusually assertive medical certificate, because I fear for her safety as a junior doctor on the edge of her capacity to cope.

“This doctor can return to the workplace,” I write, “when the hospital can guarantee that she will be placed in a team that follows the hospital’s stated values of respect and kindness.”

I don’t think this is likely, but I feel better writing it down. Later that afternoon, I ring the college and ask what she is supposed to do. They send me a policy document that also tells me they are committed to kindness, equity and respect. I give up.

My next patient is a gender-diverse person who is living with unstable housing and deep poverty. After two years, they have finally seen a specialist at the local centre of excellence for a bewildering constellation of symptoms which may be endocrine, may be neurological, or may simply be the consequence of a life of unrelenting trauma and complex PTSD.

They do not use metaphors, possibly because they have autism, so I believe it when they tell me what happened. They are seething.

“I am not going back to that hospital,” they say. “The specialist told me my GP should stick to her knitting and not meddle in things they don’t understand.”

I have no letter from the specialist a fortnight later. After many phone calls, my receptionist cannot get one, or even clarify who the specialist was. I am no clearer about what is going on, and I don’t knit. I am forced to continue meddling in things I don’t understand.

At the end of the day, it is likely I will stay back for a few hours of unpaid paperwork, including answering a report for AHPRA.

As a senior member of the profession, I take on some patients who I know are likely to be challenging, because I think I owe it to the more vulnerable doctors just starting their careers. Inevitably, I will fail these patients because their expectations are unrealistic and change often. The critique of my practice is unfounded, but takes hours of paperwork, liaison with the MDO lawyers and a lot of soul searching so I can be the reflective, contrite person the Board needs to see to ensure I am a safe person with the public.

I have no idea what I was supposed to do with this patient, whose unrelenting demands are undoubtedly the result of her own trauma and unstable attachment. It was always inevitable she would report me. I also know that AHPRA and the Board don’t actually see the complainant in full flood, and rely on her letters which even to me sound eminently reasonable. So I shove down the anger, resentment and self-doubt, and write a letter which the lawyer will vet, expressing my commitment to reflection and continuous quality improvement. It does nothing for my mental health or self-respect.

I also debrief my receptionists. They are extraordinary, and I wouldn’t cope without them. However, as young women, they are in the right demographic to be disrespected, yelled at and threatened by patients who demand to be bulk billed. They pay their tax levy, they yell, and the doctor was late, so why should they have to pay? And the minister said she is now getting three times the rebate, so what does she want? Another Mercedes?

Yet despite the systemic disrespect, the media accounts that anyone could do my job because it’s just scripts and referrals anyway, the accusations of fraud and the daily interaction with the public who ask me if I’m a specialist or “just a GP”, I do love what I do.

I just know that my ability to survive it will be shortened by the deep systemic disrespect. Like any other form of systemic discrimination and abuse, it may not be intentional. Perhaps the policymakers and leaders in the health system believe they value me. However, their behaviour suggests otherwise.

Florence Nightingale was famous for her image as “the lady with the lamp”, the devoted, compassionate angel of competence and care. However, she was a fierce advocate. She had no time for emotional displays.

“I think one’s feelings waste themselves in words; they ought all to be distilled into actions which bring results.”

Equally, she had no time for leaders and policy makers who lacked the context to make good decisions.

“What cruel mistakes are sometimes made by benevolent men and women in matters of business about which they can know nothing and think they know a great deal.”

However, my favourite quote is one I can relate to as a “lady doctor”. Florence describes the expectations she carried as a “lady doctor” equivalent: devotion and obedience. For me, the expectation that I am “devoted” to the community is expressed as “patient-centredness” and the commitment to care for any patient the nurse-led clinics, centres of excellence and outpatients departments don’t want. “Obedience” helps me avoid the attention of AHPRA, the PSR and the behavioural economists. However, like Florence, I sometimes share this sentiment.

“No man … ever gives any other definition of what a nurse [or a lady doctor] should be than this – ‘devoted and obedient’. This definition would do just as well for a porter. It might even do for a horse.”

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP, and lectures in the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. Find her on Twitter @GPswampwarrior.

Dr Erin Walsh is a research fellow at the Population Health Exchange at ANU. Her current focus is the use of visualisation as a tool for communicating population health information, with ongoing interests in cross-disciplinary methodological synthesis.