GPs are tired of suturing the wounds – our patients’, our colleagues’ and our own.

In our last column, Erin and I introduced you to the swamp: the messy, unpredictable world we GPs inhabit.

We also described the high, hard ground overlooking the swamp where increasingly specialised systems live and thrive.

The boundaries between the two are becoming increasingly impervious, and this brings me to the crocodiles.

Down in the swamp, there are many threats to a GP’s health and wellbeing – the injuries, the infections, the exhaustion and of course, the stress. Sometimes, if we become too weary, we can drown. Sometimes a patient may pull us under. They may not intend to, but when you are drowning yourself, you will grab at your rescuer, and that doesn’t always end well.

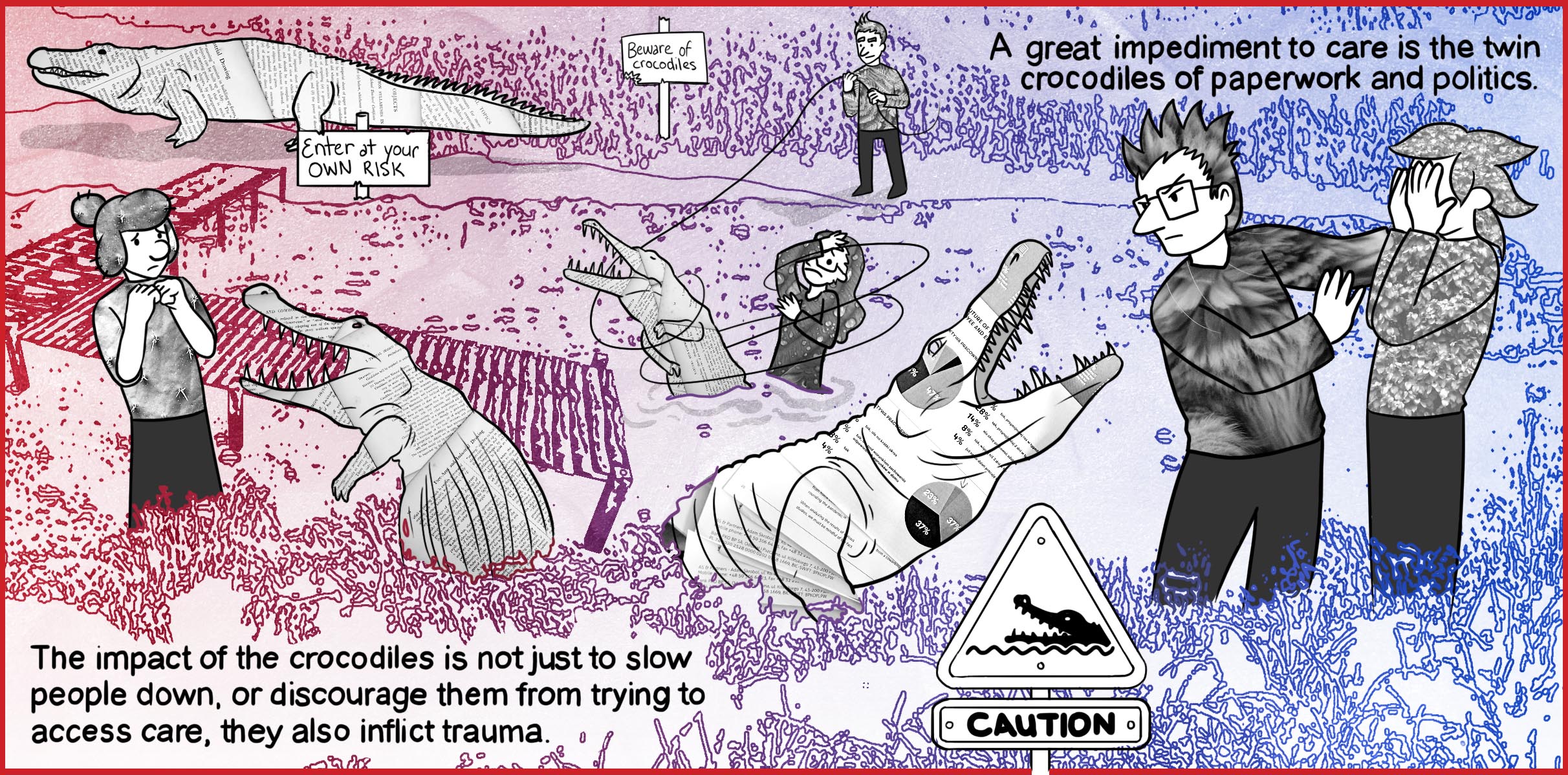

But for many of us the greatest impediment to care is the twin crocodiles of paperwork and politics. These crocodiles aren’t native to our swamp, which often means we don’t really understand them. Most of them are introduced species. Like cane toads, they were released into this habitat to deal with specific problems, the plagues of “low-value care” and “excessive billing” the politicians perceive in the system. Political crocodiles require us to duck and weave, predicting their path so we can protect our patients and our businesses from potential harm.

We don’t deny that there are sometimes species that need culling, but we do disagree with the extent and the method of eradication. Crocodiles have other things in common with cane toads: nobody likes them, nobody thinks they are a good idea, and they breed relentlessly.

The paperwork variety of swamp crocodile was originally bred to patrol the high grounds, ensuring only the best, brightest and bravest could get access to tertiary care. Nobody denies the need to have a system that defines who gets care and why, of course, and there has to be some form of triage for such an expensive and precious resource. But being crocodiles, they’ve spread out to occupy most of the ecosystem.

Unfortunately, crocodile handlers have difficulty listening to the guides on the ground who see the more vulnerable people fall victim to the fierce behaviour of their pets. It’s a bit like vicious guard dogs. “He’s a gentle giant, really, and exceptionally good with children” they say, as they introduce their favourite predator. These expert handlers just don’t understand how dangerous and terrifying crocodiles are to the uninitiated and vulnerable. They’ve created an environment that is increasingly hostile and dangerous.

Some crocodiles are merely annoying, and although they waste resources, they are not particularly dangerous. Think of the “Get a note from your doctor” species of paperwork.

This includes certificates to get a refund on your golf club membership because you were in hospital, the medical clearance for the gym, and the certificate to say a toddler is no longer an infectious risk and can return to childcare to pick up another infection. These crocodiles contribute nothing to the ecosystem, they consume resources, and are profoundly irritating.

It’s the government-sponsored crocodiles who do the most damage. Take any government system – the NDIS, DVA, Centrelink, Medicare etc. – and there will be a float of crocodiles just itching to slow the patient down and create a barrier to recovery. They impede the passage of patients, carers and GPs through the system and form a natural barrier to access.

Any GP will tell you that these crocodiles can sap your will to live. At the moment, GPs are doing up to a day of unpaid labour each week avoiding, fighting, placating and feeding crocodiles, while we try to shepherd our patients into the care they need. The crocs slow us down, distract us from patient care and reduce the financial sustainability of the practice.

However, the impact of multiple crocodiles is more insidious.

Like any predator, they pick off the weakest first – patients who are unprotected, too busy to access alternative systems of care, too poor to pay the gap to access my services as a guide, lacking the literacy to learn how to wrangle crocodiles, and lacking the health literacy to understand the ecosystem. These patients often end up abandoned in the middle of the swamp.

I asked a father and son recently how they got their income. Both were sleeping rough. They described going to Centrelink several years ago, and being directed to a computer they couldn’t understand. Recently, they tried again, and left with a multi-page document they couldn’t read. I asked again how they got their income. “We beg,” they said.

The impact of the crocodiles is not just to slow people down, or discourage them from trying to access care, they also inflict trauma.

We often think about cost shifting, and the way state and federal governments squabble over money like seagulls going after a chip. However, I see a more painful form of cost-shifting, where the Department of Social Services inflicts trauma by commission (Robodebt) or omission (inadequate payments and a lack of housing) and then shifts the cost to us in healthcare. We are the ones who manage the health impacts of trauma and neglect.

I am tired of suturing crocodile wounds. But at the moment, I am also suturing my own wounds and the wounds of my colleagues, because the crocodiles have recently started coming for us.

They are the nudge letters, the Medicare fraud debacle, the new CPD requirements and various over-zealous governance systems that we are expected to wrestle with ever-decreasing financial support.

We also have new “guides” in our ecosystem, who are well supported to take the more lucrative patients on to their boardwalks, leaving us to traverse the swamp with the most complex and needy patients with less resources than ever. I think I could almost cope with that, but when we have boardwalkers like Trent Twomey from the Pharmacy Guild shouting insults from the heights, it’s a bit disheartening.

Every hour I spend wrestling crocodiles is an hour taken from patient care. I would love permission to shoot some of the bastards. I recently watched a documentary on cane toads, where the residents of Humpty Doo were waxing lyrical about their ingenious cane toad eradication schemes.

Of course, they don’t really work. But I’d settle for some culling.

In the end, every intervention we make in the swamp has an impact on sustainability, cost, workforce and equity. We know that patients with the least privilege have the greatest health needs, and the least access to services. If we could cull some of the low-value bureaucracy, listen to the experience of the guides, and support the most needy patients to access care, we would have a better system.

But the missing element is, I think, trust.

Without trust in the swamp guides, the crocodile handlers will still try to control us, doing things to us, not with us, to influence care. And eventually, the crocodiles will drive most of us out of the swamp altogether.

We know we are losing general practice, the most effective and efficient part of the health system, and that experience and wisdom will not easily be replaced. I blame the moral distress of being unable to help patients because we are too busy wrestling crocodiles.

What an extraordinary waste.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP, and lectures in the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. Find her on Twitter @GPswampwarrior.

Dr Erin Walsh is a research fellow at the Population Health Exchange at ANU. Her current focus is the use of visualisation as a tool for communicating population health information, with ongoing interests in cross-disciplinary methodological synthesis.