The digital stethoscopes used to detect AI-generated videos have been missing a trick.

It’s to my regret, and your probable relief, that I announce this will be my last Back Page, as I’m leaving The Medical Republic after six years.

In that time I’ve been a political and clinical reporter, TMR editor and political news editor, clinical news editor, opinion editor, and most importantly, wrangler of the Humoural Theory and Back Page columns.

It’s been an honour to keep you informed of clinical advances and the political and professional matters affecting general practice and the nation’s health.

It’s also been a pleasure writing for an audience smart and discerning enough to appreciate (or at least pardon) writing on topics as tangential as stupid big cars, romantic typologies, brain vitrification, space microbes, sweary surgeons, tripping barbarians, 16th-century anatomy, bed rotting, fake centenarians, D&D, how cats are better than children and 5000-year-old osteoarthritis patients, to give just a few recent examples.

So let’s go out with something weird.

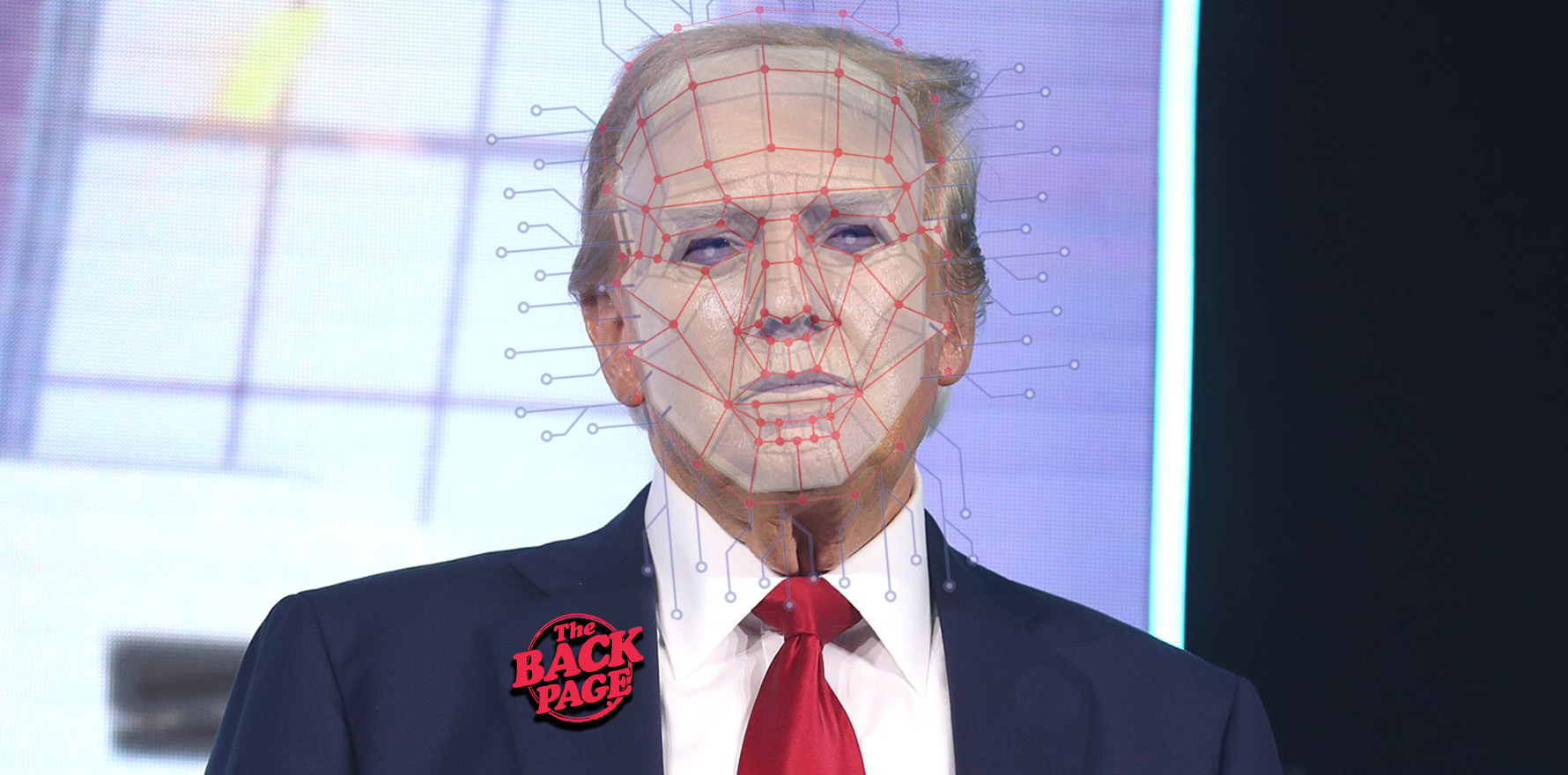

If you live on this planet you’ll have been exposed to AI-generated video of Donald Trump licking and kissing Elon Musk’s feet. I didn’t say you wanted to come in contact with it, or that you weren’t quite unwell after it, only that you almost certainly saw or heard about it.

The video, which was beamed on to monitors at the US Department of Housing and Urban Development two months ago to protest the unelected Musk’s reckless rampage through government, is just one of the more prominent examples of deepfake videos – one with a relatively wholesome purpose.

This new paper, published in Frontiers in Imaging, tells me two things I didn’t know about this next-level digital clownery:

1) The absence of a visible pulse allows deepfake detection through techniques such as remote photoplethysmography.

2) Sorry, deepfaked people have pulses too.

“The cardiovascular pulse, inducing individual pulsating blood flow in human skin, causes subtle color variations that are assumed to be plausible in genuine videos only,” the authors write. “However, contrary findings indicate that deepfakes can indeed exhibit a one-dimensional signal resembling a heart rate (HR), further complicating the detection process.”

They go on to prove that deepfakes are slipping past the detectors by (to cut a long and technical story very short) generating a cutting-edge deepfake detector designed to extract and analyse heartbeats in videos using rPPG, generating fake videos from real source video, and finding heartrate signals in these and a range of other deepfakes, including older ones.

By monitoring the real heartbeat of their subjects during filming, they are able to determine that the convincing heartrate derives from the source video, so there isn’t even the need for deepfakers to deliberately add it.

For deepfake detection algorithms to be trustworthy, they write, they need to switch from global readings to more localised ones.

“Recent advances in video-based vital sign analysis have moved toward capturing local pulse signals from specific facial regions which better reflect the anatomical blood flow patterns of the human face,” they write.

But the bigger medical story here is that where there’s a heartbeat there’s the potential for arrests and arrhythmias, murmurs and myopathies, fibrillations and flutters.

Who is taking care of the heart health of these unreal individuals as they go about subverting democracy and engaging in degrading virtual behaviour?

Someone deepfake a team of cardiologists and upload them to the interwebs, stat.

So long – send specious and spurious story tips to grant@medicalrepublic.com.au.