Working for ourselves can leave us especially prone to overwork and an eternity on call.

Among the commonest reasons cited for GPs setting up solo include not seeing eye to eye with business owners, lack of flexibility with working hours and an inability as contractors to set the standard for how we wish to practise medicine, including and especially around charging fees.

With the freedom that comes with going out on your own come the inevitable downsides: working on the business side of general practice and taking on excessive responsibility.

What are some of the dangers?

- Not delegating work to administrative staff but doing everything ourselves

- Not having reception staff act as buffer between doctors and patients

- Being accessible to patients between appointments for non-urgent or new issues as they crop up

- Being accessible to patients via text messaging or similar

- Guilt at charging a gap fee and therefore providing patients with “more” to justify the fee

Some refer to these as an “annoyance tax”. Others speak of it as a badge of honour: “I want to do everything I can to be of help to my patients and I reply to every email/message I receive”.

At heart, most of us are people pleasers afraid of disapproval and anger, so we go to great lengths to avoid them.

Then we wonder why we have no clear demarcation between our work and private lives, especially if we’re female, and why life feels so hard.

We wonder, as this dermatologist in the US did, why people take us for granted and don’t appreciate our efforts to help them.

We wonder why they’re outraged when money is mentioned, especially after we’ve given advice for free.

Here’s what I think.

- We generally don’t value what costs us nothing, e.g. a bulk-billed GP appointment. When we pay nothing, or not much, we are less invested. When we pay more, we also pay more attention (and expect more).

- We don’t generally value other people’s things and time the way we do ours, hence the late cancellations and no-shows for appointments. (Some people don’t even seem to value their own time, so it would never occur to them to value someone else’s.)

- If we don’t understand that someone is doing us a favour, we can’t be grateful for it, e.g. a discounted fee.

It may rankle to hear this, but that doesn’t make these facts any less true. Our psychology and psychiatry colleagues understand this as it’s a key element of the training and healthy boundaries of the therapeutic relationship.

Nowhere else in medicine are we taught this explicitly.

Is access to healthcare a universal right? Yes, it is, and the reality remains that making it entirely free at point of care means that many of us won’t appreciate it.

As doctors we aren’t taught about the business of medicine, of making money, or of talking money without shame. So most of us bring our own money stories into every consultation.

It’s why many of us expect reception staff to discuss money with patients and get upset if the patient raises the topic with us.

I’ve had colleagues say to me “It’s not right as doctors that we should discuss money”, “I’m not comfortable talking about money, I’d rather someone else do that” and even “It’s fine for you to discuss money with patients if you’re comfortable, but it’s not something I’m interested in doing.”

In every other facet of life we expect to discuss money, including with other healthcare workers. Common examples: dentists and orthodontists, psychologists and psychiatrists, physiotherapists and more.

It’s a vital part of informed financial consent, so why make someone else relay it on our behalf?

As a surgical trainee, I was taught that “the person doing the procedure does the consent” with few exceptions. Yet when it comes to fees, we’d rather delegate that admin to a person with no skin in that fee and then feel annoyed when the person gets it wrong by charging a 23 for a long appointment or bulk billing.

Related

My view is that some things are so important, we need to do them ourselves to ensure they’re done right. That means understanding why we need to be OK talking money with our patients: when we charge, how much we charge and whether we work for free if they contact us between appointments. Ideally we want to lay the foundation for this before it is needed.

When we are unclear we cause confusion. I might see a patient today and charge the consultation fee. I may recall them to discuss a result next week and be prepared to bulk bill that, except the patient says “While I’m here doc, I’ve another problem I wanted to discuss with you.” We are now stuck with a new problem and a longer consult. But if the patient has been told they’ll be bulk billed, and now they have to pay, there will be resentment at the mixed signals. When are they expected to pay a fee and when will they be bulk billed? Or discounted?

Other similar scenarios:

- Patients emailing descriptions or photos of new concerns instead of making an appointment.

- Patients asking to be rung back about a new but related non-urgent issue between appointments – “She has my notes on file, she can call me when she’s free”.

- Patients sending across paperwork – “She can fill this in her free time and let me know when to pick them up thanks!”

- Patients messaging us on social media – “I rang/emailed but since you work alone and part time I thought I’d let you know so you can check.”

- Patients texting for scripts they’ve lost or asking for scripts when they’ve not been seen for months.

On the face of it, it doesn’t seem like much.

It’s “just a script” or “just a quick phone call”, right?

Except each of these additional “minor issues” adds up to hours of unpaid admin time after we are done consulting and cutting into our downtime with family.

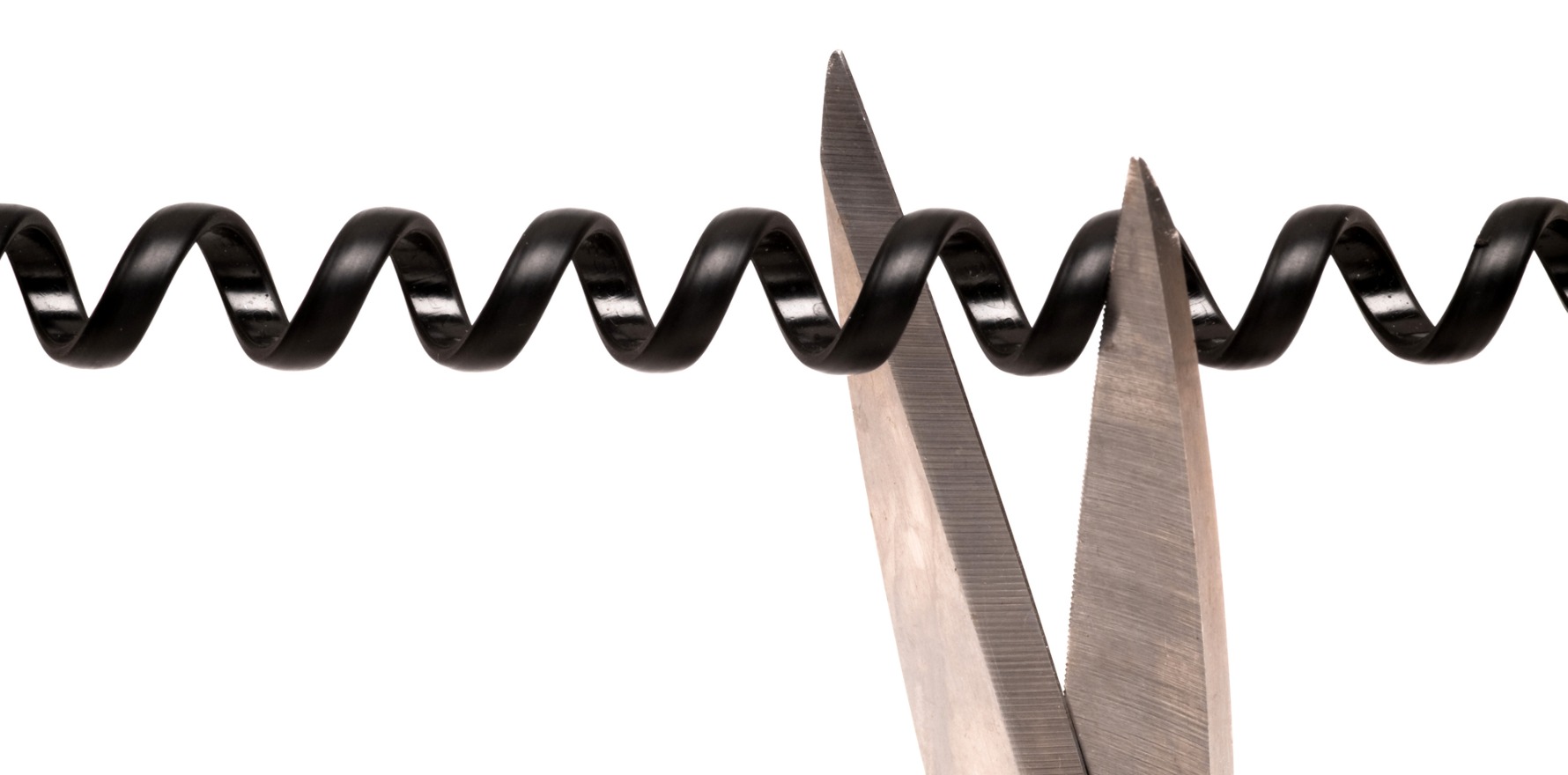

It’s being expected to be on call for everything that is important enough for them to reach out but not enough to make an appointment nor to pay for it.

That’s what opens the door to resentment, frustration, burnout.

So as I say, “boundaries are for me.” They cannot be enforced on anyone else. They are there to let someone know the limits to what I will tolerate. They are also a means to let people know what the consequences of breaching that fence will be so they can decide if they will stay or leave.

No anger, no vitriol, no resentment.

We cannot please everyone, as much as we want to.

Will you feel guilty if you follow through? Yes. Will you feel resentment if you say yes when you want to say no? Yes.

So when I feel guilt, I ask myself which of the two yeses above is worse. And then I choose the yes that is the less guilt-inducing.

Your mileage may vary.

Dr Imaan Joshi is a Sydney GP whose practice includes aesthetics; she tweets @imaanjoshi.