How come we think drug companies are just bad when their products mostly do good?

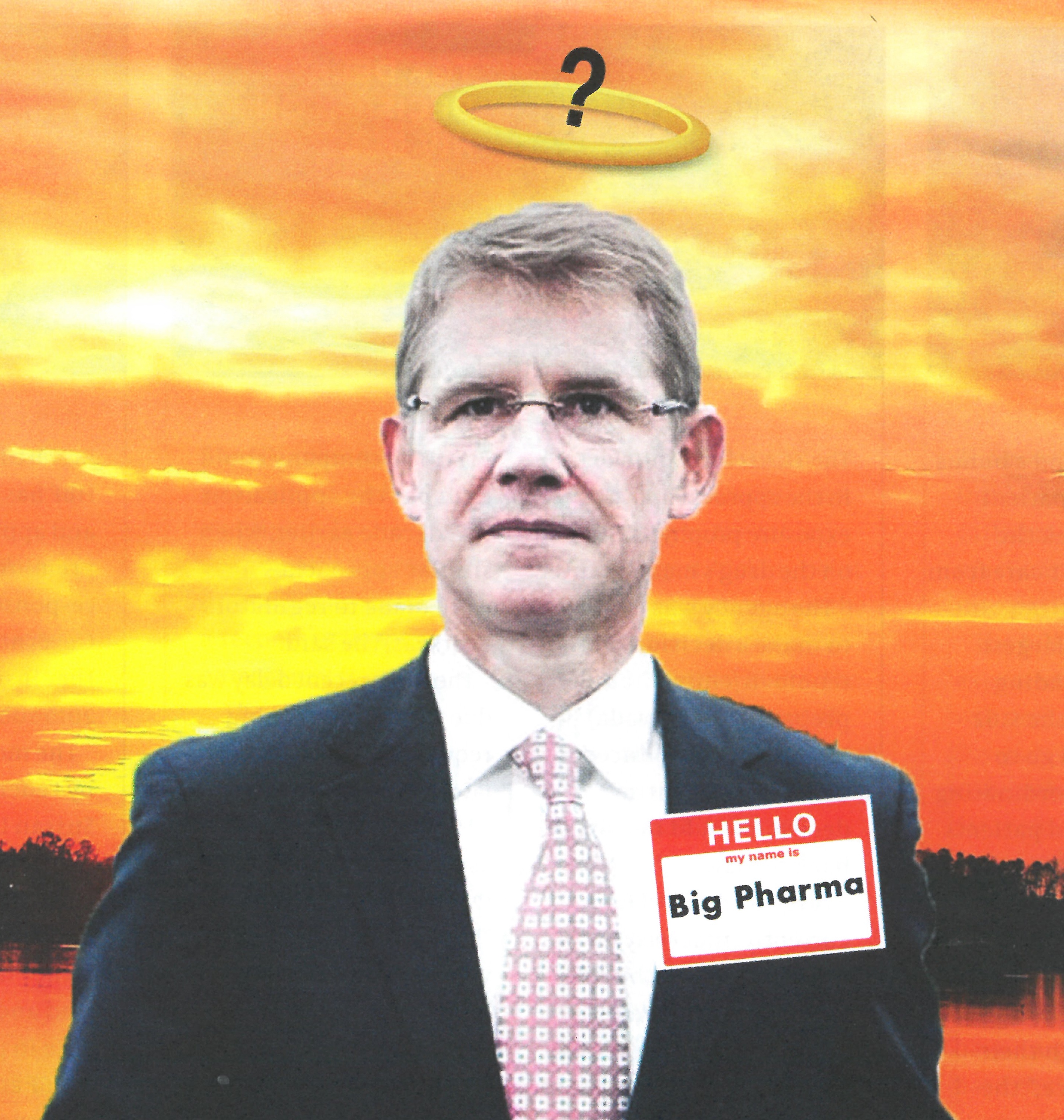

Is Big Pharma’s poor public image finally about to improve? One straight talking CEO is giving it his best shot

It has always been intriguing to me that in surveys about trust and goodwill, pharmaceutical companies almost always score lower in people’s minds than tobacco companies. How does that work? Tobacco companies produce a product that we know is deadly and kills millions of people each year. They lied about this fact for many years in an attempt to cover up the awful truth and today, after being found out, they persist in peddling the product, now with renewed vigour into the Third World in order to offset declines in the Western world.

Pharmaceutical companies, no matter which way you cut it, produce products that save or make billions of lives better each year. OK, they definitely aren’t saints. Episodes such as the Vioxx cover up, of which there have been many similar examples over the years, and some past strategies such as questionable HIV drug pricing in the Third World, don’t exactly engender a lot of trust. But the incidence of stuff like this is no greater or less than in other industries. If you put enough people together in an organisation making a lot of money, at some point, the organisation breaks down, and under pressure of some sort, individuals and groups within companies do the wrong thing.

Let’s say we did somehow establish that pharma companies were actually certified evil doers, holding us all to ransom by charging exorbitantly for their products in order that we can keep ourselves healthy, or creating markets for conditions which don’t actually exist (a claim made by many anti-pharma campaigners over the years). Then you’d have to say the collateral damage of all that evil activity is still massively on the positive side of the ledger for human kind – billions of people’s lives made better or saved every year.

None of this matters, apparently. We still don’t like them, and think generally they are up to no good. In the many years I’ve worked in healthcare, I’ve never met a new medical journalist that didn’t come to the job thinking drug companies are bad.

Discussing the phenomena with many doctors and medical journalists over the years, the prevailing view of why this happens seems to be that you just can’t be seen to be making a profit out of saving lives or helping people maintain their health.

Who then would want to be a pharmaceutical company CEO? Sure, the pay is probably pretty good, but thereafter it feels like it’s all downhill. You are essentially the devil. When your kids grow up and learn what you did, they will never forgive you. So it was with great interest that I read Harvard Business Review’s (HBR) Top 100 CEOs of 2015. Guess who topped the list? Yep, a pharma CEO. Novo Nordisk’s Lars Sorensen.

That is no mean feat. HBR and the institution of Harvard Business School are world leaders in organisational theory and development. The HBR top 100 CEO index compiles lots of data before arriving at its result. They are at the forefront of the charge to encourage companies to look well beyond their profits and give equal weight to the wellbeing of their employees and their community.

The cynics among us might suggest this is just a new tactic which has at its endpoint the goal of making more money. Actually, that’s pretty clear. But the fact is, it is still mostly upside for the wider community. I quite like the idea.

So apparently does Lars Sorensen, because he is now ranked number one by an organisation that champions companies that genuinely care about the wellbeing of the community, the environment and their employees – all alongside obligatory shareholder returns.

When asked what was the key to his success by HBR, you get an instant sense of the man. He doesn’t go the route you typically might see in high-flying career CEOs from the US (Sorensen is Danish). He doesn’t say anything about a brilliant strategy, the development of a great management team, who then undertook masterful execution. No, Sorenson says the key to his success has been luck. There is something viscerally honest and humble about that answer.

Sorenson is clearly a very talented executive, but in many ways, his answer is correct. He came to the right company at the right time. Novo Nordisk was founded in the 1920s to make insulin, then a newly discovered substance. In 1983, Sorensen arrived at the beginning of massive upturn in demand for solutions to a rapidly expanding health issue around diabetes. And he was pragmatic and focused in his approach to solving those issues after stumbling a few times.

“Since I joined the company, 33 years ago, I’ve been part of some of the most stupid mistakes,” he told HBR. “One of the worst was trying to get into glucose monitoring. I could share many, many similar examples. So over the past 20 years, we’ve been narrowly focused on the thing we’re really good at.”

That thing is remedying the emerging diabetes crisis.

Sorensen is very straightforward about why there is a need for a company to be properly committed to social and environmental responsibility. “Our philosophy is that corporate social responsibility is nothing but maximising the value of your company over a long period of time, because in the long term, social and environmental issues become financial issues. There is really no hocus-pocus about this.”

He isn’t necessarily critical of companies that don’t act in this manner though. He says in most circumstances companies that don’t embrace these values are under shareholder pressure to create short-term value as opposed to strengthening long-term sustainability.

“Shareholders can move their capital around with a flick of a finger, yet in pharmaceutical research it can take more than 20 years to develop a new product. If we cure diabetes and destroy a big part of our business, we can be proud.”

Sorensen says he has a Scandinavian leadership style, which is consensus-oriented, but he flavours it with a touch of pushiness, something he learned from a six-year stint as a manager in the US.

He is also a firm believer in being properly in touch with the pulse of your staff. If you are serious about this, you must understand and be fair about the financial relativities between senior management and staff, he says. Despite being the top of the 100 CEO index his pay is among the lowest on the list.

“My pay is a reflection of our company’s desire to have internal cohesion”, he tells HBR.

“When we make decisions, the employees should be part of the journey and should know they’re not just filling my pockets. And even though I’m one of the lowest-paid people in your whole cohort [HBR’s Top100], I still earn more in a year than a blue-collar worker makes in his lifetime.”

On staff motivation, he says he has it easy.

“People like to do exciting things. They like to be part of the journey in which we’re saving people’s lives. So we bring patients in to see employees. We illuminate the big difference we’re making. Without our medication, 24 million people would suffer. There is nothing more motivating for people than to go to work and save people’s lives.”

If you’re interested in HBR’s full interview with Sorensen, you can find it at: https://hbr.org/2015/11/novo-nordisk-ceo-on-what-propelled-him-to-the-top